The Glory of Vishnu

Tracing the Origins of Palm-Leaf Manuscripts

Giovanni Ciotti and Sebastian Bosch

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Texts.

SUB Hamburg

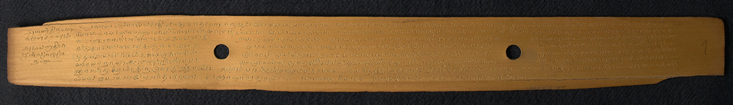

Manuscript Cod. Palmbl. III 118 originates from India, and more specifically from the area corresponding to today’s Tamil Nadu. As usual for manuscripts from this region of the world, it is made of palm leaves. The leaves are boiled, polished, and cut to size in order to form a uniform stack of folios that can then be written on. Wooden boards are usually added at the front and back of the stack. In palm-leaf manuscripts from South India, a metal stylus is used to incise the letters on both sides of each leaf. The incisions are usually then inked by smearing the surface with a paste consisting of a mixture of soot and herbal oil.

Inking did not take place in the case of Cod. Palmbl. III 118: most probably commissioned for shipment to Europe, the manuscript was never smeared with the soot-based paste, and was probably therefore never read. This invites us to reflect on the different histories that Indian manuscripts had during the colonial period.

The text in this particular manuscript is a commentary (c. 13th century) by Periyavāccāṉ Piḷḷai on the Amalan̲ātipirān̲ (“The Unblemished Lord”), which are ten hymns (pācurams) composed by the Vaishnava saint Tiruppāṇ Āḻvār. These hymns are just a tiny section of the Nālāyirattivviyappirapantam (also spelled Nālāyiradivya-prabandha), which can be translated as “Four Thousand Divine Hymns” (current redaction datable to c. 9th–10th century), a devotional text praising the glory of Vishnu, one of the main divine figures in all the various branches of Hinduism. The text is composed in Tamil, and more specifically in its more sanskritised register, Manipravalam, which is closely associated with the cult of Vishnu in Tamil Nadu.

Tamil is now one of the 22 scheduled languages of the Indian Republic, and its literature reaches back to at least the beginning of the common era. Tamil was also officially recognised as one of the classical languages of India in 2004. Manipravalam enjoys a somewhat unique status in the history of Tamil literature, since a matter of great controversy in modern times has been the question of how to perceive and describe the relationship between Tamil and Sanskrit.

Devotees in temples throughout Tamil Nadu now often recite the Nālāyirattivviyappirapantam in a particular style that shares intriguing similarities with the style used for reciting the Sanskrit Vedas. A rendition can be heard here.

Sebastian Bosch

Cod. Palmbl. III 118 is not only one of the very few palm-leaf manuscripts to bear the scribe’s colophon, i.e. the scribe’s final statement providing information such as his own name, the datewhen he completed the manuscript, and the title of the text. It also tells us exactly where the manuscript was copied, namely in Thirunarayanapuram.

Profiling the material features of this manuscript and of a sizeable number of other manuscripts that are also explicit about the place of their provenance will allow us to compare them with the material profile of other manuscripts that do not record where they were produced. We would then be able for the first time to identify the place of origin of the many thousands of manuscripts in libraries across Tamil Nadu and partly in Europe. The local history of these manuscripts is unknown, since no records have been kept of their exact provenance.

Sebastian Bosch

We can profile the material features of palm-leaf manuscripts through methods including phytolith analysis, proteomics/metabolomics, microscopy, and spectroscopy that have never, or hardly ever, been used to study such written artefacts before. Our aim is therefore twofold. On the one hand, to test whether it is at all possible to study palmleaf manuscripts using methods of analysis long used to study, for example, European codices made of parchment or paper. On the other, to enable us to reconstruct the literary history of Tamil Nadu and the circulation of the texts that were composed and transmitted there (i.e. who read what and where).

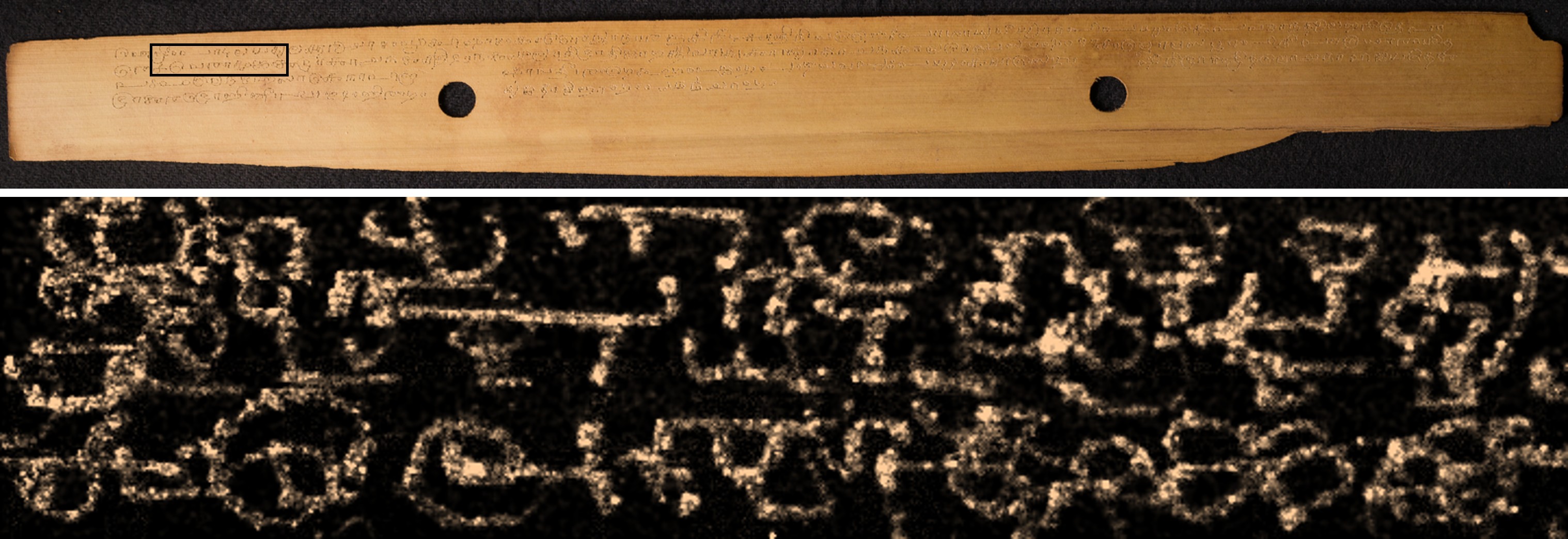

Initial results have already shown that X-ray fluorescence analysis (spectroscopy) can be used to detect clear differences in the elemental composition of palm- leaf manuscripts from different regions. Further methods should confirm these results in the future and make the material profile even more precise.