Margins Matter

Content and Paracontent in Ancient Study Manuscripts

Christian Brockmann, José Maksimczuk and Daniel Deckers

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Texts.

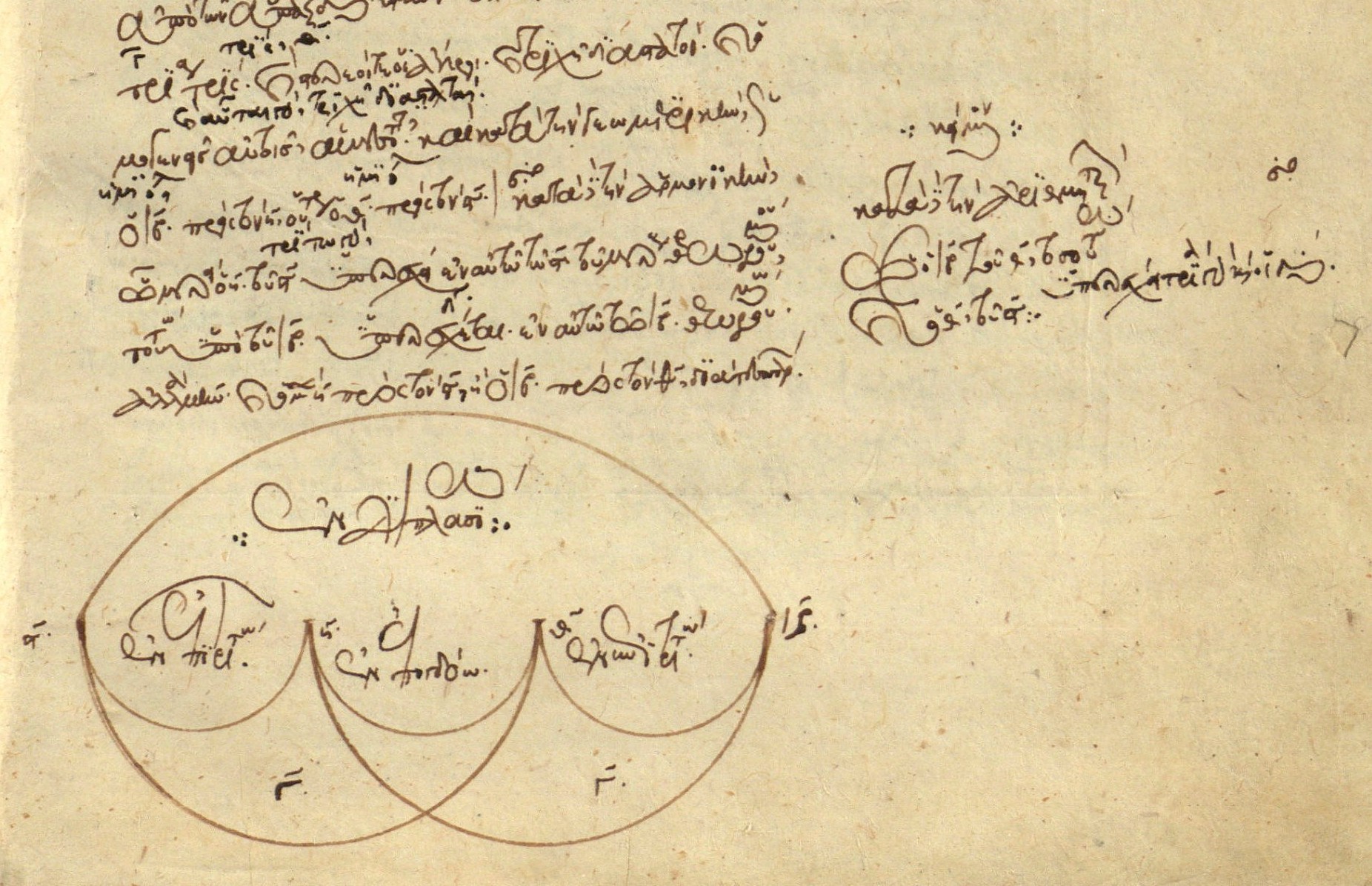

Cod. philol. 88 was originally an integral part of a much larger manuscript. The first part is also still preserved and is kept in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Barberinianus graecus 164). While the more extensive Vatican volume contains Aristotle’s logical treatises with numerous marginal annotations, the Hamburg codex consists mainly of Nicomachus of Gerasa’s Introduction to Arithmetic (2nd century CE). It was originally followed by Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics with an introduction and explanations by the commentator Eustratius of Nicaea (12th century) added in the margins, but unfortunately all this section, apart from two leaves, has been lost. The manuscript was probably produced in Constantinople. From a corresponding note in the Barberinianus gr. 164, we know the name of the scribe and the exact date when the manuscript was completed: the two parts, now separated, were written by Alexios in 1294. Unfortunately, little is known about the scribe and who might have commissioned him to do the work.

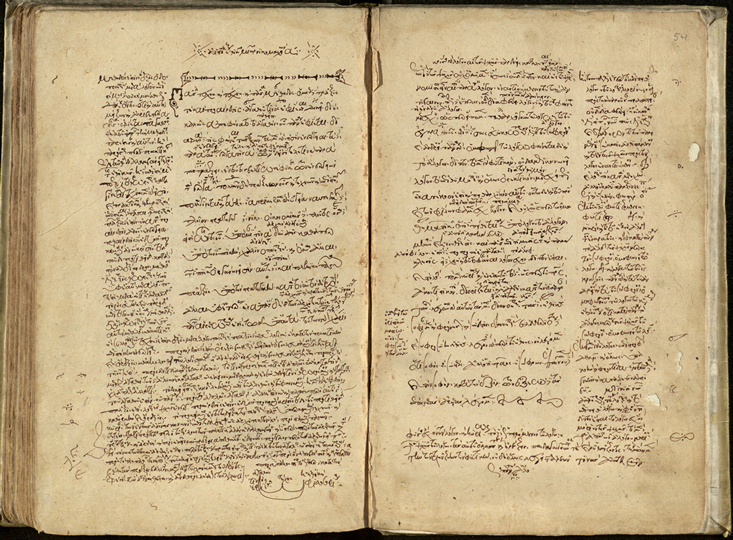

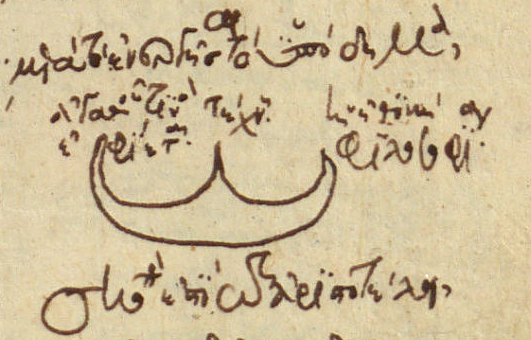

The codex was designed as a working or study manuscript, and only a few of its pages have decorations, these being simple. In the part of the manuscript in Hamburg, the scribe copied a multigraphic paracontent divided into scholia, as well as numerous diagrams drawn with great accuracy and care, and some tables with overviews of the contents alongside the core of Nicomachus of Gerasa’s Introduction to Arithmetic. As for the visual organisation of the contents, the scribe added numbers, technical terms, and keyword-like explanations in interlinear notes, as well as occasional marginalia with longer explanations regarding the intricate core text. In addition, there is chapter numbering in the margins and further paracontent and corrections by later users, both Eastern and Western, including by Georgius-Gennadius Scholarius (c. 1400 – c. 1472), the first Patriarch of Constantinople after its conquest by Mehmed II in 1453.

SUB Hamburg

Nicomachus of Gerasa studied Pythagorean and Platonic philosophy, as well as music and mathematics. All that has been preserved in its entirety from his extensive oeuvre is a handbook of musical theory and the Introduction to Arithmetic, these being used as teaching manuals up until the Middle Ages. The latter, along with the comparable work by Theon of Smyrna (1st and 2nd century CE), served primarily to convey the fundamentals of mathematics for the purpose of helping scholars understand philosophical texts; besides a philosophical introduction, it included sections on number theory, fractions, and number relations.

As a working or study manuscript, the Hamburg codex illustrates the practice of heavily annotating manuscripts in the context of use, and the interplay and interdependence of core and paracontent. This is apparent in both its textual sections, in the Introduction to Arithmetic, and in the few surviving pages of the Nicomachean Ethics. F. 53v will serve as an example. Here, we find the beginning of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, whose famous opening sentence contains an obvious error, since the term τέχνη (techne) is repeated: πᾶσα τέχνη . καὶ τέχνη . καὶ πᾶσα μέθοδος .ὁμοίως δὲ πρᾶξις τὲ καὶ προαίρεσις, ἀγαθοῦ τινὸς ἐφίεσθαι δοκεῖ. Reference signs are added above the last words of the sentence and repeated in the left margin below the corresponding parts where commentary is given. The exegetical marginal notes, going back to the Byzantine scholar Eustratius of Nicaea, begin at the top left with an explanation of the term methodos as the “fundamental ability to use reason to pave one’s way (to the goal)” (μέθοδός ἐστιν ἕξις ὁδοποιητικὴ μετὰ λόγου, cf. Eustratius 7,13 Heylbut, CAG 20; and see also John Philoponus 6,27–28 Vitelli, CAG 16). It is then emphasised that the term episteme (knowledge, science) is not mentioned in the first sentence (ἐπιστήμης δὲ οὐκ ἐμνήσθη). The paratext offers several reasons for this conspicuous absence, one being that, if techne and methodos strive for some good, then this naturally applies much more to episteme (cf. Eustratius 7, 17–25 Heylbut, CAG 20).