History of a Fragmentary "Sūra of the Cow"

The Longest Quran Excerpt on Papyrus

Mathieu Tiller, Naïm Vanthieghem and Claudia Colini

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Texts.

SUB Hamburg

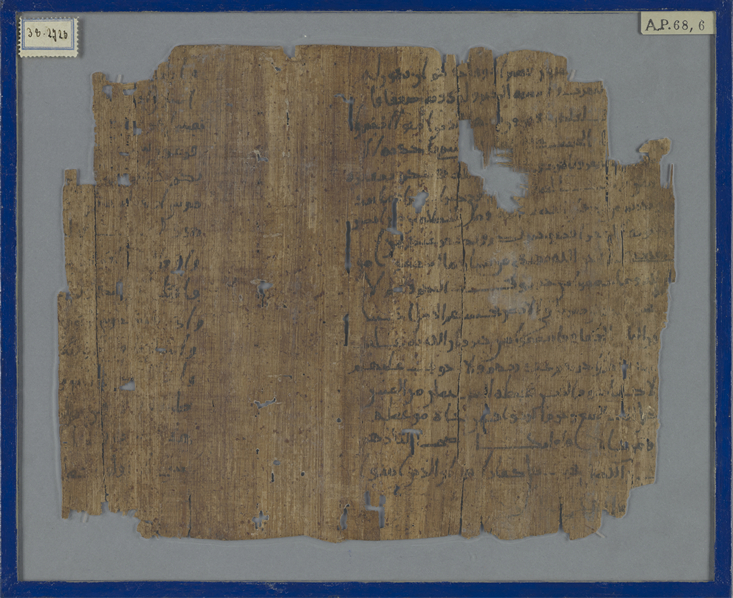

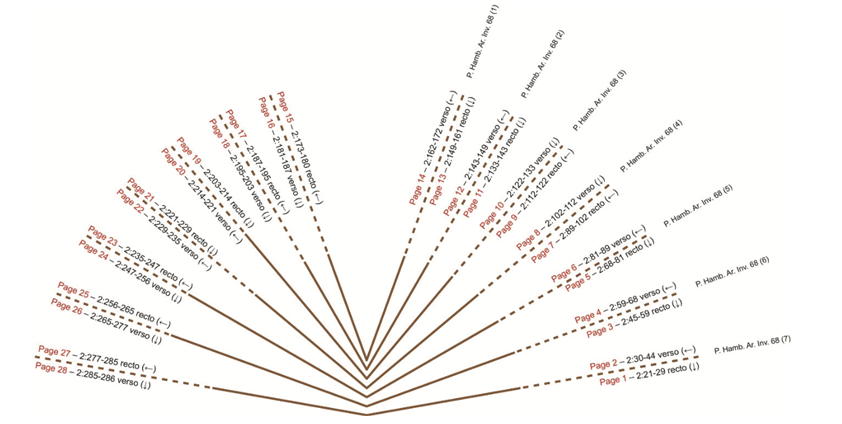

P. Hamb. Arab. 68 was discovered in Egypt in the first quarter of the 20th century, and brought to the State and University Library, where it remained unidentified for nearly a century. The manuscript is to date the longest extant extract of the Quran preserved on papyrus, since most of the early Quranic codices discovered so far were written on parchment. It was probably copied in al-Fusṭāṭ, the Egyptian capital, in the late 7th or early 8th century, and moved to Upper-Egypt, where it was probably unearthed. This fragmentary quire consists of seven bifolia, or 28 pages, and includes almost the entire second Sūra (“The Cow”). Like the earliest Quranic codices, P. Hamb. Arab. 68 was copied in an archaic script called Ḥijāzī, the most typical feature of which being the slender, inclining appearance of many letters, and the shape of the qaf in its final position,, whose end tail resembles an “S”. Like other early Quranic codices, P. Hamb. Arab. 68 often adopts a defective spelling, leaving out many long vowels that modern orthographic standards demand. Some diacritical dots are used to distinguish homographs (for example, the letter depending on the diacritics has three phonetic values ب /b/, ت /t/ or ث /th/). As in other Ḥijāzī manuscripts, dividers were added between verses. Concentric circles of dots separate groups of ten verses. In addition to tenverse markers, there are series of short dashes, arranged in columns in a rectangular pattern, that separate some individual verses. The text of the Sūra ends with two scrolls of a decorated headband (Fig. 1) followed by another short text, probably a final prayer, which is not part of the Quran.

Claudia Colini

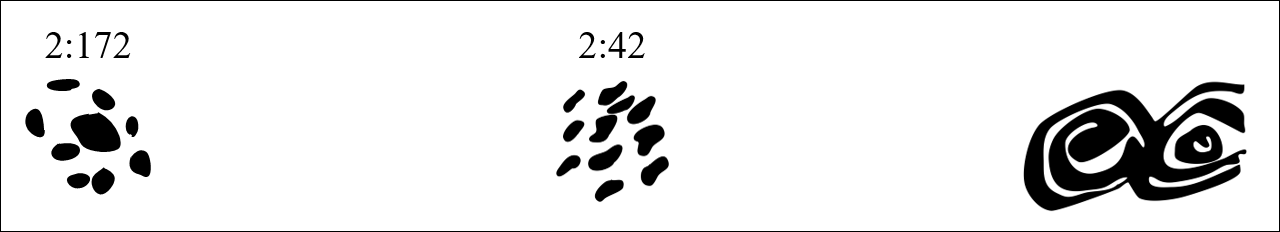

The manuscript is written in a carbon-based ink, a type commonly used in Egypt, especially in legal and administrative contexts. Using X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF), we detected traces of copper in the ink of the main text and the diacritical dots (Fig. 2), possibly due to the presence of the metal in the water or to contamination from a copper or bronze inkwell. No impurities were observed in the decoration and, albeit less clearly, in the verse markers, suggesting that they were penned with a different ink.

Claudia Colini

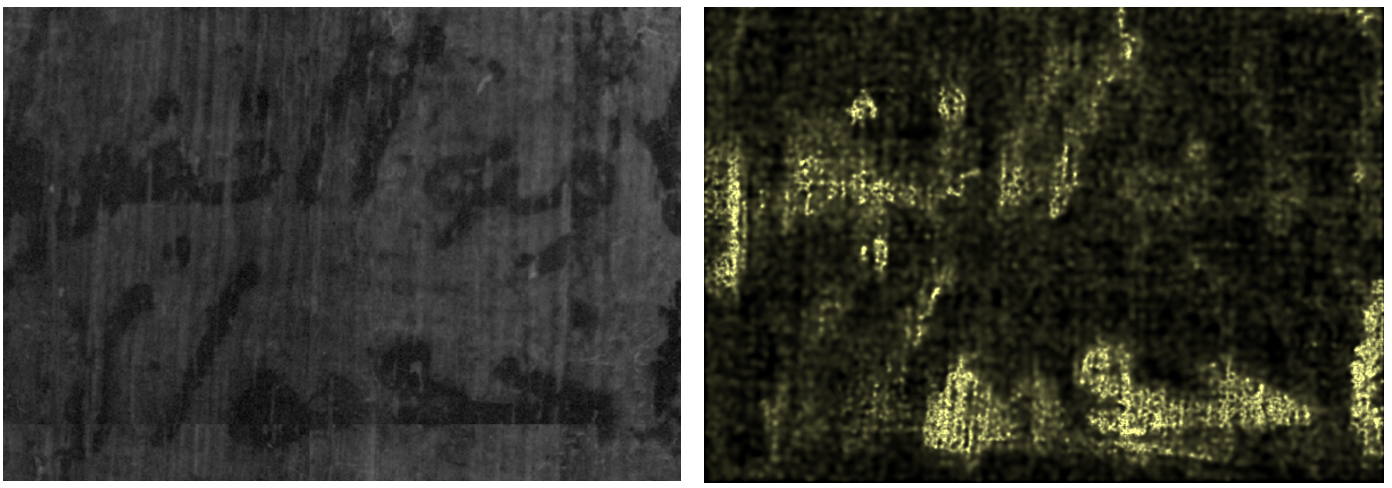

The quire was side-sewn or overcast, as can be deduced from the double series of sewing holes still visible on the right and left side of the fold. This and other codicological evidence suggest that P. Hamb. Arab. 68 was an autonomous booklet that contained only the Sūra of the Cow (Fig. 3). This suggestion deserves all the more attention since several Islamic and Christian sources from the early Islamic period (including John Damascene’s book on heresies) claimed that Muslims had originally had several sacred books, including a “Writing of the Cow”. The legal scope of the Sūra of the Cow may have justified circulating it autonomously, as a kind of vademecum for the nascent community.

Claudia Colini

The Sūra preserves traces of 37 textual variations, most of which have no effect on the text’s general meaning. In a few instances, the copyist corrected his mistakes. Comparing the text of the Sūra to the ʿUthmānic recension of the Quran, now used as the canonical reference text, reveals four important omissions, the most striking of which relates to verse 219 of the ʿUthmānic recension:

“They ask you about wine and gambling. Say: ‘In them both lies grave sin, though some benefit, to mankind. But their sin is graver than their benefit’. They ask you what they shall spend. Say: ‘The surplus of possessions’. Thus does God make clear His signs to you. Perhaps you will reflect.”

P. Hamb. Arab. 68, however, omits the central part (in italics). Even if merely a copying mistake, this means that some Muslims used a copy of the Quran missing the main verse prohibiting wine and gambling.

Due to the high number of variations and omissions, P. Hamb. Arab. 68 seems to have been quickly discarded and destroyed, perhaps by being torn into two halves.