The Deceitful Father

A Marriage Certificate and a Family Feud

Claudia Colini and Daisy Livingston

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Texts.

SUB Hamburg

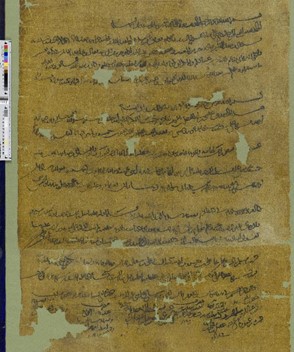

P. Hamb. Arab. 1 is a marriage record dealing with the financial settlements of the union between ʿĪsā ibn Abī al-Faḍl ibn Makhlūf and Khibāʾ, daughter of Khalīfa ibn Thābit ibn Suraqa. Both were from mercantile families in the provincial capital Al-Bahnasa, previously known as Oxyrhynchus and situated in Middle Egypt.

The manuscript is clearly divided into three blocks of text, written on three occasions covering a period of 15 years. The first and longest text (on the upper two thirds of Fig. 1), written in an elegant cursive hand, dates to 12 Jumādā al-Ūlā 604/4 December 1207. After a preamble outlining the benefits of marriage and citing the Quran, the text records that the bride was owed 35 gold dinars as a marriage gift: ten to be paid upfront, with the remaining 25 to be paid in annual instalments over the next twelve years and six months. In this transaction, the bride is represented by her father Khalīfa, who was legally obliged to deliver the money to his daughter. The statements of six witnesses follow the text in columns, providing the transaction with validity.

SUB Hamburg

second text with the statements

of the various witnesses marked

in white and the remarks of the

judge outlined in yellow.

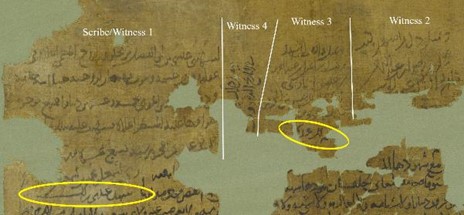

The second text (Fig. 2), added beneath text 1 and starting about two-thirds of the way across the page, dates to 13 Muḥarram 617/20 March 1220, and shows that ʿĪsā had completed the payment of the gift, now in the possession of his father-inlaw Khalīfa. Four witnesses testified to this, including the scribe of the document, Ismaʿīl ibn Muḥammad ibn Ismaʿīl. The other three statements have an unusual position, since they appear to the right of the text, with one even being written perpendicular to the other writing on the page and in a darker ink (witness 4). This suggests that the statements might have been added on a second occasion, although they bear the same date as the document itself. Despite this unusual arrangement, at least two of the witnesses passed the judge’s assessment, the judge recording his verdict on the reliability of the witnesses beneath their statements, as part of a legal procedure to ensure the validity of transactions.

SUB Hamburg

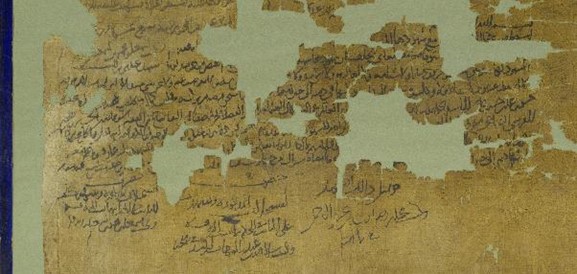

The final text (Fig. 3), partially incomplete on account of the holes in the cloth, was written on 13 Ṣafar 619/29 March 1222 by the same scribe that had written text 2. It reports that Khibāʾ swore an oath before a judge, complaining that she had not received the money from her father. This kind of oath is not a procedure commonly attested in legal documents and was probably necessary because there was no other way of obtaining evidence that the money had not been paid. The statements of three witnesses, including the scribe, follow the text in the usual column layout. Unfortunately, no final receipt appears in the manuscript to testify that the sum was finally handed over.

Lauren Nishizaki/Claudia Colini

of a plain weave (A) shows that it is the same type.

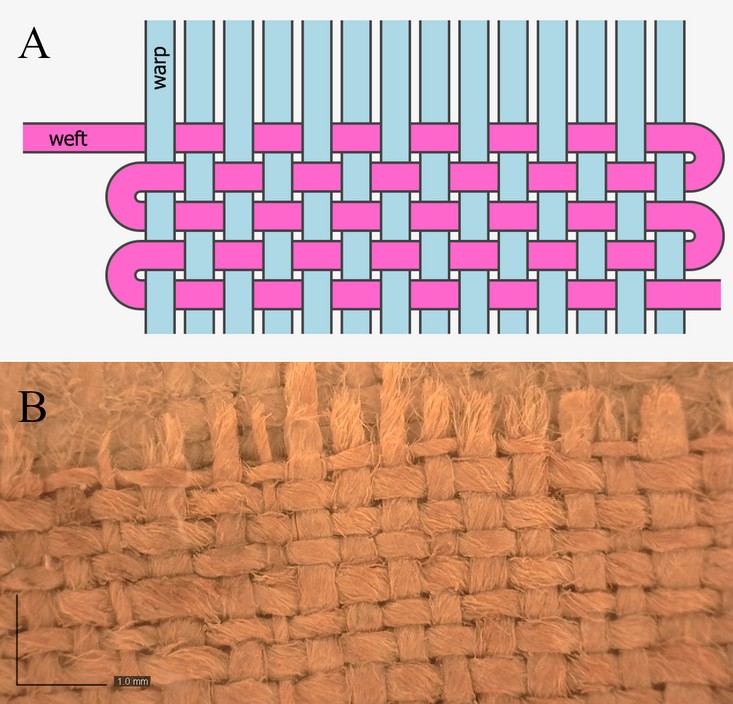

The documents are written on two similar pieces of light-yellow linen of analogous dimensions and glued together to form a larger piece with a size of 101.3 × 45.4 cm. The textile is woven in a common plain weave, the yellow colour being the result either of a dye or degradation of an originally white cloth (Fig. 4). Linen was an unusual material for legal documents, but it had some precedent for marriage records and was perhaps selected to give these artefacts a special status and durability. Since the bride came from a family of cloth merchants, it is possible that they could acquire a piece of cloth easily, and that the cloth was less costly for them than parchment or high-quality paper.

All the inks used in this manuscript are carbonbased, which suggests that only one ink was used on each occasion, the exception here being text 2, where the ink employed by witness 4 is visibly different, despite his belonging to the same class as the other inks. To confirm these hypotheses, we are currently using additional techniques to identify mixed inks and to differentiate inks based on their impurities.