A High B for the Prima Donna

The Second Version of Georg Friedrich Händel’s Radamisto

Ivana Rentsch

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Texts.

SUB Hamburg

This double page spread from Act III of George Frideric Handel’s Radamisto reveals the English opera history of the early 18th century as if under a magnifying glass. It offers an insight into the musical practices of the legendary Royal Academy of Music at London’s King’s Theatre. These practices have long since faded and only materialise as fragments in this score. It is a copy that Handel made together with his copyist John Christopher Smith in 1728, when it was a question of re-arranging Radamisto, already composed in 1720, for the revival. As suggested by its designation as a director’s score, Handel used the notes to conduct the performances, which he did from the harpsichord, a practice typical of the period. Due to the copy’s designation as purely utilitarian material, every intervention in the score documents a practical necessity with regard to the performance. In other words, the corrections reveal artistic decisions that were only made shortly before or during rehearsals.

This applies to several passages on the double page on display. On the left-hand page (folio 20 verso), there is a continuous correction of the vocal part and the basso continuo in the last three bars of the recitative above. In addition, the crossedout beginning of the subsequent aria “Barbaro partito” is conspicuous, whereas only at a second glance does it become apparent that several pages, which undoubtedly contained the continuation of the erased beginning of the aria, have been cut out. Instead, the right-hand page (folio 21 recto) now contains the transcription of the exact same aria “Barbaro partito”, but now in B flat major instead of A major. In retrospect, the fact that Handel changed the key of the aria explains the corrections on the left-hand page, since a recitative necessarily had to end in the key of the aria that immediately followed. In this case, some skill was required. Although the fundamental notes of B flat major and A major are only half a tone apart, they are far apart harmonically. The profound musical corrections in the last three bars of the recitative (folio 20 verso) are due precisely to this.

Geral Coke Handel Collection, Foundling Museum

The question is obvious: given that the aria had already been successfully performed on the same stage in A major in 1720, why did Handel transpose an otherwise unchanged aria by half a tone? From our perspective today, this shows a very different weighting of the composer’s will on the one hand, and the importance of performance on the other. Far removed from the “faithfulness to the text” demanded today, the opera score served as the basis for a performance that could be changed almost at will depending on the general conditions. The decisive factor for the artistic standard of the Royal Academy of Music was not primarily the composers, but the singers. Even Handel, who was famous throughout Europe, was unable to change this. On the contrary, because the opera company had an illustrious circle of patrons, including George I, the artistic, i.e. singing, demands were prioritised.

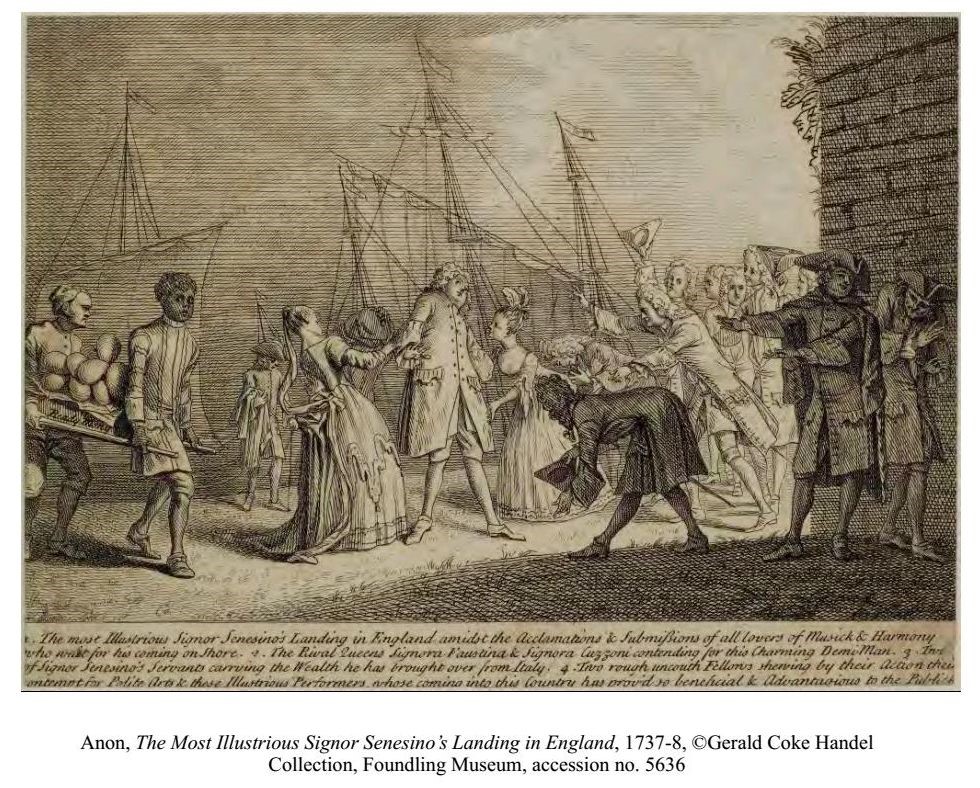

London, and with it the Royal Academy of Music, co-administered by Handel, was one of the most important centres for the almost ludicrous cult of castrati and prima donnas throughout Europe. Vast funds had to be raised to engage the castrato Senesino in 1720, the soprano Francesca Cuzzoni in 1723, and the soprano Faustina Bordoni in 1726. The star ensemble was very famous and a constant topic of conversation in society and the press, as evidenced not least by a wealth of surviving caricatures. The sources suggest that Handel also found it extremely difficult to deal with the celebrated performers: as soon as one was annoyed and did not want to perform, the performance had to be cancelled. For example, when Cuzzoni refused to sing the aria “Falsa imagine” in Ottone, Handel called her a real devil (“veritable Diablesse”), adding that he himself was the chief of the devils (“je suis Beelzebub le Chéf des Diables”). Nevertheless, Handel was largely at the mercy of the demands made by his stars.

SUB Hamburg

Cuzzoni sang the role of Polisenna in Radamisto in 1728, and thus also the aria “Barbaro partito”. This explains the transposition to B flat major in the score of the 1728 production: though unnecessary for aesthetic reasons, the transposition was made because she would not have been able to sing the high B flat (Cuzzoni’s top note) in the original A major. It is obvious that she insisted on this, especially since her no less famous rival Faustina Bordoni, who could “only” shine with the high A, was also on stage as Zenobia. Handel’s own opinion played no role here: compared to the two “rival queens”, even the most famous composer was a mere servant.