Provenances of the Hamburg Papyri

Collecting in colonial contexts

Jakob Wigand

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Texts.

SUB Hamburg

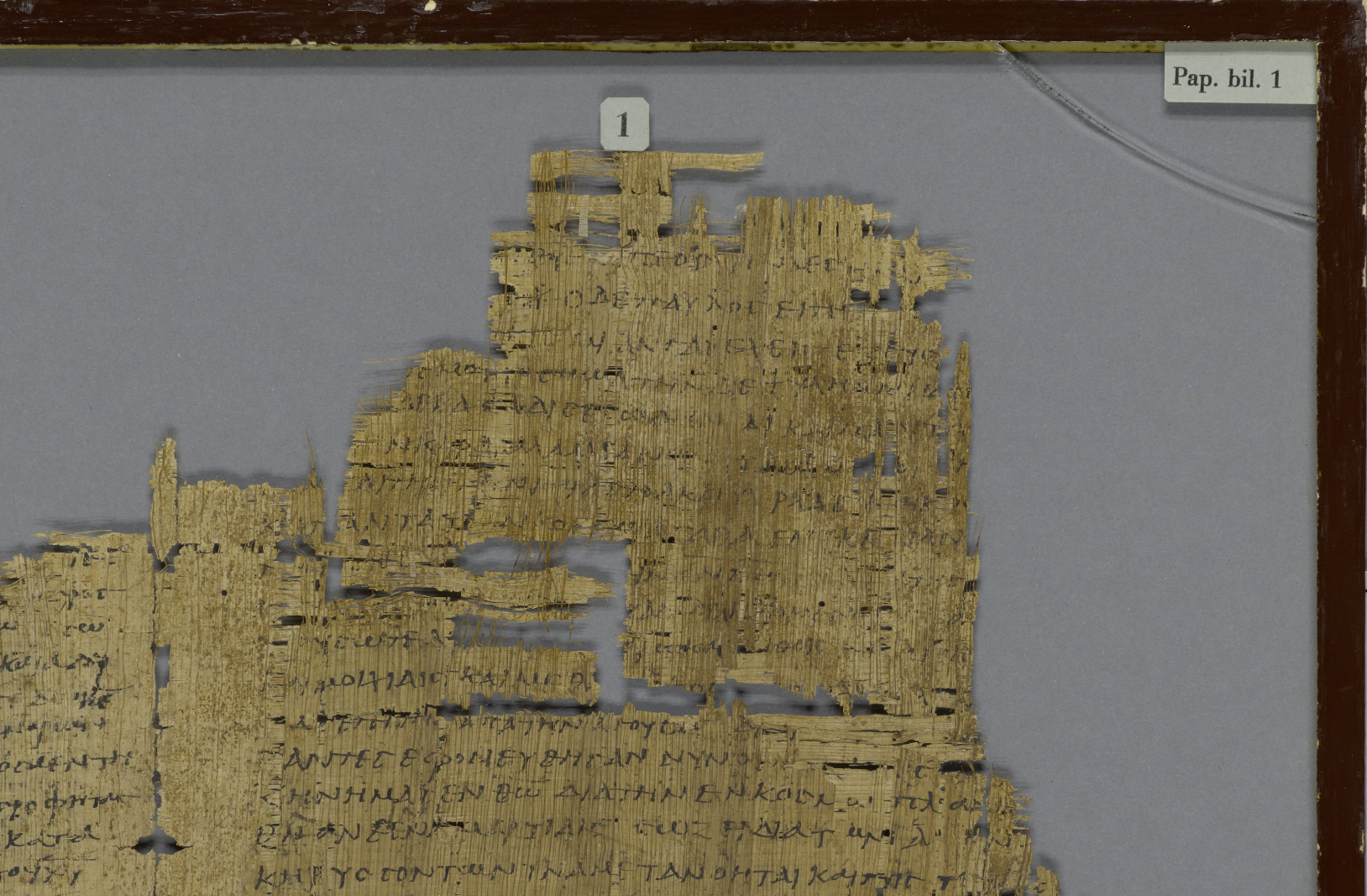

Among the manuscript collections of the Hamburg State and University Library, the Papyrus Collection is a large one. Containing over 1,100 papyri of different ages, scripts, languages, and materials, the diverse collection is held together by the common origin of the pieces: all the papyri in the collection come from Egypt and have been in Hamburg since the early 20th century. But how did the library get hold of these papyri? And did it do so legally?

The Hamburg Papyrus Collection was founded in 1906. At that time, the Hamburg City Library joined the German Papyrus Cartel, an organisation that aimed at acquiring papyri jointly for several German collections. The library paid an annual sum into a joint account and thus secured shares in the purchases made by the cartel, primarily of Greek papyri. From 1907 to 1914, numerous papyri came to Hamburg thanks to the activities of the cartel. In addition, from 1910 to 1914, Arabic papyri were purchased with a separate budget via the present-day German Archaeological Institute in Cairo.

SUB Hamburg

At the time of these acquisitions, Egypt was not an independent state, but was subject to a British military government. The Egyptian Antiquities Authority was headed by French officials. Researchers from other nations repeatedly tried to influence its legislation and decisions. Although the Egyptian laws contained principles of modern cultural property protection, they were not an expression of a sovereign Egyptian nation, especially since they were only half-heartedly enforced. Instead, the laws were the result of colonial rule. In particular, the regulations for the export of papyri and other antiquities were often interpreted in favour of European collections. The collectors at the time knew this; they emphasised the ‘favourable conditions in Egypt’. Colonialism thus facilitated the building of European papyrus collections.

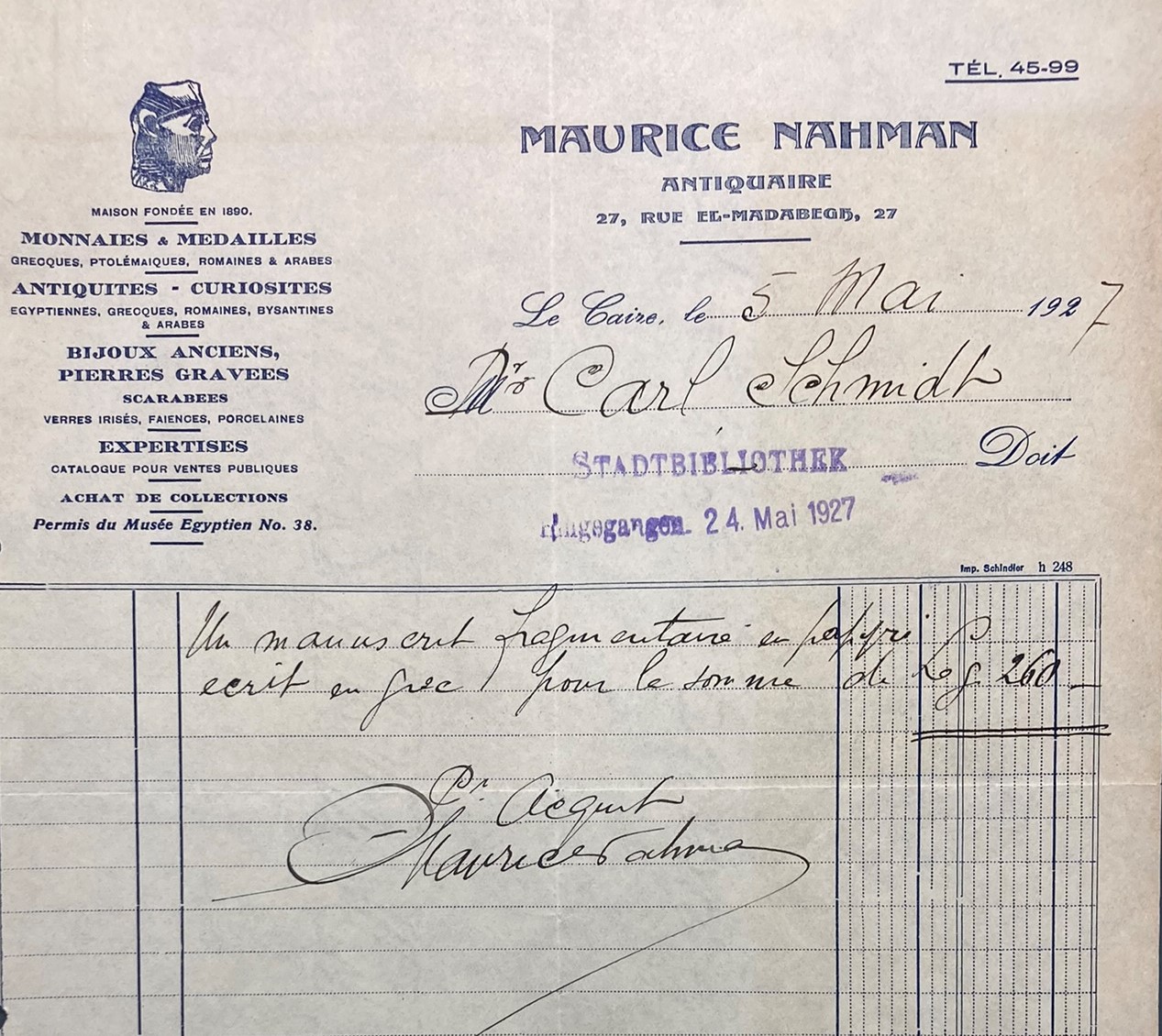

After the First World War, it became increasingly difficult for the library to buy papyri, for several reasons. The Papyrus Cartel had ceased to exist, the prices for antiquities had increased, and the library suffered from financial difficulties. Moreover, the Egyptian state had tightened its protection of cultural property. With Egypt’s formal independence in 1922, more and more Egyptians demanded that Egyptian cultural assets should be researched, preserved, and exhibited in Egypt. Consequently, the Egyptian Antiquities Law was enforced more rigorously. This development can also be traced down in the archival records, that are preserved at the SUB. For example, in a letter to the director of the SUB, the Coptologist Carl Schmidt complained about stricter controls by the Egyptian antiquities authority: ‘Exports are becoming increasingly difficult; it is impossible to get good pieces through legally. Director General Lacau is proceeding very rigorously’ (SUB Hamburg, Cod. Hans.III:10:6, Carl Schmidt to Gustav Wahl, 29.03.1929).

Despite these stricter regulations and controls, Carl Schmidt and the papyrologist Wilhelm Schubart continued to purchase new papyri for the collection of the State and University Library in the 1920s. In many cases, the exact circumstances of these purchases could not be clarified beyond doubt because of lacking documentation. Thus far, no export licences, which would prove that the purchase and export of a piece were legal, could be found for any Hamburg papyrus. In the case of some pieces, there is reason to suspect that items have been exported illegally without necessary authorization.

The research on the provenance of the Hamburg papyrus collection shows that further investigations should be more closely integrated into the current debate on collection items from colonial contexts. This debate deals, among other things, with the highly topical question of the responsible handling of immoral or illegal acquisitions. The Cluster, the SUB, and the Research Centre of Hamburg’s (Post)Colonial Heritage aim to investigate the provenance of the papyrus collection and to initiate fair solutions.