Holiness and Authority

Manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible: Codex and Torah Scroll

Irina Wandrey und Michael Kohs

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Texts.

SUB Hamburg

These written artefacts – a Torah scroll intended for synagogue worship and a codex – each contain what Judaism regards as the most important part of the Hebrew Bible: the five books of Moses. According to Jewish tradition, Moses received the Torah from God on Mount Sinai.

In the Middle Ages, a new, previously uncommon type of written artefact was introduced into Jewish manuscript culture: Codices, i.e. bound books. Before this time, the Bible as well as other texts were written down and used in scrolls, similar to the Torah scroll shown here. Codices containing the text of the Hebrew Bible first appeared in the 8th century CE in the Mediterranean and Middle East. One of the important innovations in these codices was the integration of the so-called masorah into the Biblical text, which previously

consisted only of consonants. The masorah includes vowel signs (nikkud), cantillation signs (te‘amim) and a kind of “critical apparatus”: the so-called small masorah (masora ketana) provides the reader with statistical information such as word frequencies and grammatical-linguistic information on certain words or sections of text. The large masorah (masora gedola) lists the references and parallel passages for the words dealt with in the small masorah.

Among other things, the masorah served to protect the text from changes and distortions. The pronunciation of the text of the Hebrew Bible, which until then had only been handed down as consonants, was particularly prone to errors.

SUB Hamburg

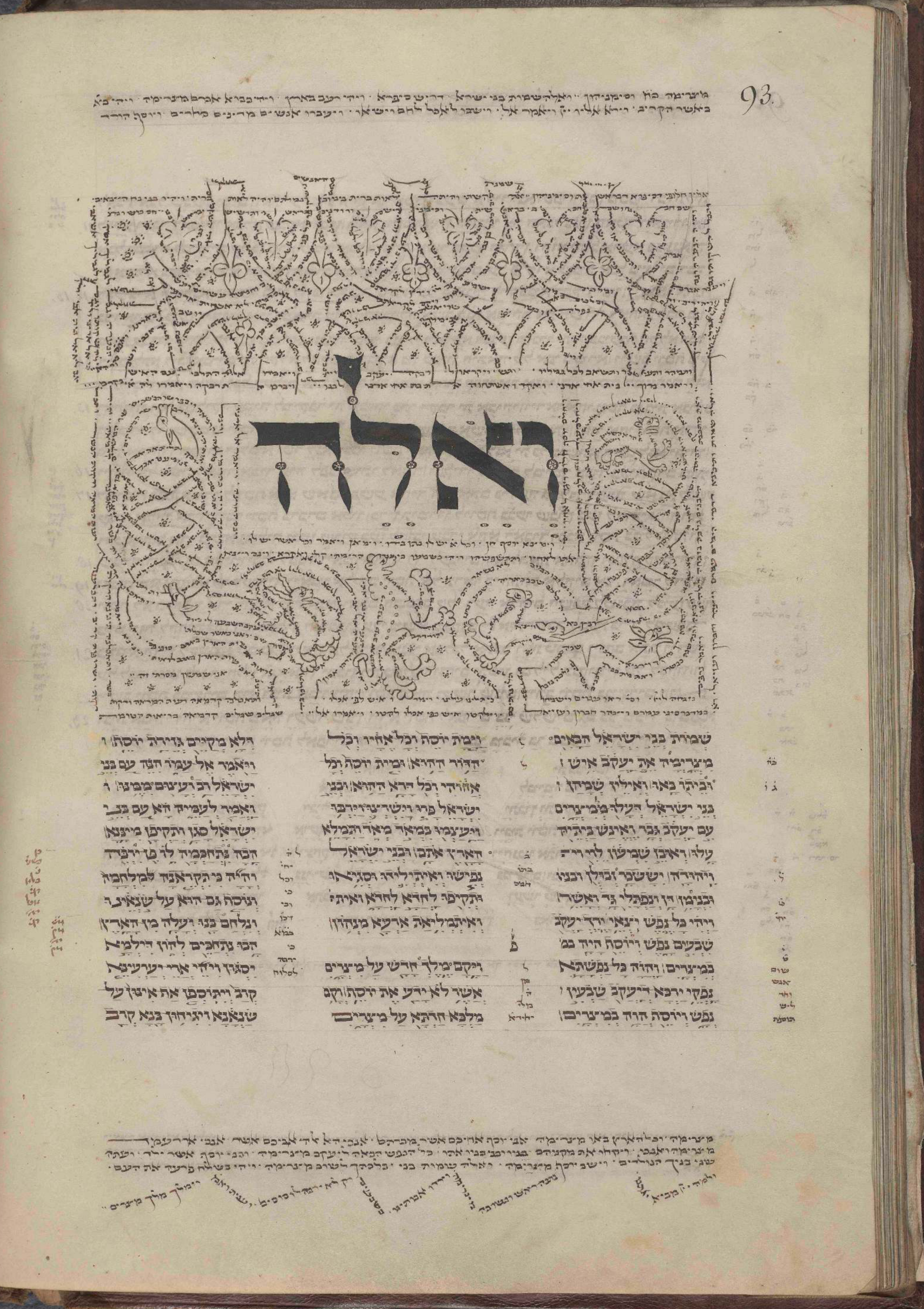

Cod. hebr. 4 dates from the 14th century, and was produced in the Ashkenazic region, i.e. central Europe. The pages opened show the beginning of the second book of Moses, Hebrew Shemot ‘names’, Latin Exodus ‘exodus [from Egypt]’. Unlike Latin manuscripts of the Middle Ages, Hebrew manuscripts of this period do not mark the beginning of a text or a new section by a large initial letter, but rather by an enlarged initial word. Another special feature of Jewish manuscripts is the framing of the initial word by a micrographic image. This image consists of very small writing, which is formed into ornamental patterns or figurative representations. The text executed here as micrography is a Masoretic compilation of Bible verses from the immediate surroundings of this page (i.e., the end of Genesis and the beginning of Exodus) and very similar or even identical verses from other parts of the Bible.

SUB Hamburg

In addition to the actual biblical text in Hebrew, the manuscript contains other texts. Each Hebrew verse is followed by an Aramaic translation (Targum) of the verse, also written in the Hebrew script. The Targum has its origins in antiquity, when Aramaic, a related Semitic language, replaced Hebrew as the vernacular. Even though Aramaic had long since ceased to be a colloquial language for Jews, the tradition of reading and studying the Aramaic text alongside the Hebrew when studying the Bible (and sometimes also in the synagogue) was maintained during the Middle Ages.

In the three-column text the vocalisation and cantillation marks are clearly visible. They were added after the writing of the main text in an additional working process, very frequently by a scribe not identical with the scribe of the biblical text. The small masorah is found on the right and left margins of the columns, the large masorah on the upper and lower margins.

Codices like the one shown here were used for text study, and they also served as a representative status symbol. For the reading from the Torah, the five books of Moses, in the Jewish service, however, the use of a codex is not permitted. The text must be read from a Torah scroll, the Sefer Torah. To this day, a Torah scroll used in Jewish worship must written by hand.

SUB Hamburg

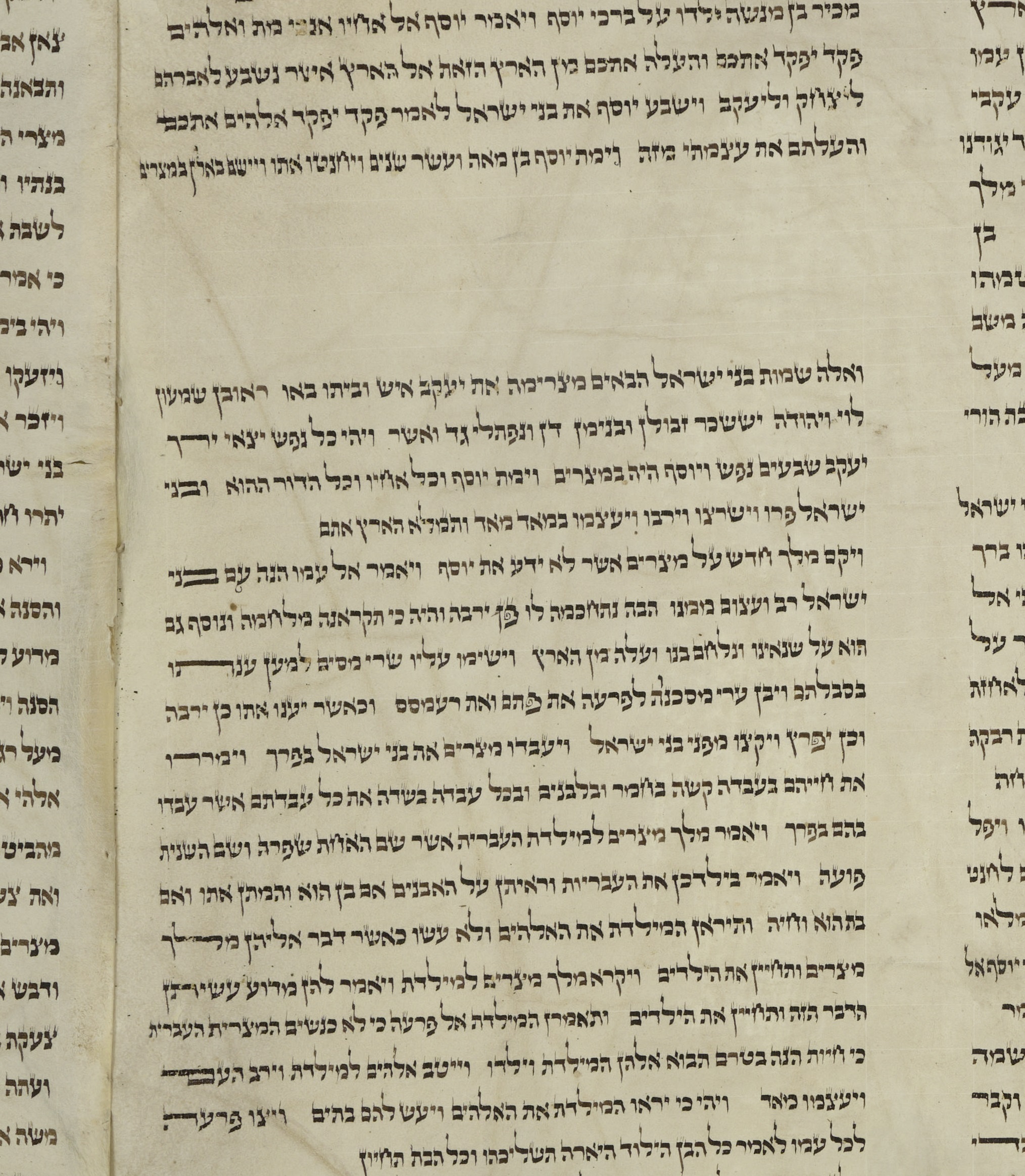

The Torah scroll Cod. hebr. 376 probably dates from the 17th or 18th century and stems from the Ashkenazic region. Only a small number of complete Torah scrolls from the Middle Ages or even earlier (for example among the ancient Dead Sea Scrolls) are preserved. As with the codex shown, we selected the beginning of the Book of Exodus for the scroll. The visual design of the text in the Torah scroll differs significantly from that of the codex. As even those who are not familiar with the Hebrew script will notice immediately when comparing the scroll and the codex, the biblical text is not vocalised here, that is, the vowel and cantillation signs are missing. Those who recite from the Torah in the service have thoroughly rehearsed the text and its melody in advance. The text of the Torah is divided into 54 sections, parashot. One complete section is read per week in the services, so that the reading of the entire Torah is completed after a year, and begins from the start. The festival of Simchat Torah, “Joy of the Torah”, celebrates the conclusion of the annual Torah reading cycle; it takes place directly after the Feast of Tabernacles Sukkot and falls in September or early October.

Special rules apply to the making of the scroll and the writing of the text. For example, the parchment for the Torah scroll must come from kosher animals and must be prepared in a specific way. The text is written by a specially trained scribe, the Sofer STaM. The acronym STaM stands for Sifre Torah, Tefillin and Mezuzot. The Tefillin (phylacteries) are traditionally worn by male Jews at morning prayers and contain parchment slips with handwritten verses from the Torah (Ex 13: 1–10; 11–16; Deut 6:4–9; 11:13–21). The mezuzah, a capsule attached to the doorpost, also contains a usually handwritten parchment slip with passages from the Deuteronomy (Deut 6:4–9 and 11:13–21).

British Library

Torah scrolls, as well as Tefillin and Mezuzot, do not show extensive decorative elements. For example, they never contain illustrations or text highlighted by colour. However, certain letters are marked on their upper side with one or three small lines, the tagin “crowns”. These are a very characteristic element of the three types of manuscripts mentioned who are all used in ritual context. In addition, in order to achieve a uniform line length in the columns, individual letters can be stretched in their horizontal length. This peculiarity of visual design is applied in the same way in Hebrew codices.

The Torah scroll, which is kept in a special cabinet in the synagogue and used in the service several times per week, is a ritual object that is held in high reverence. This is evident in its manufacture as well as in its use. When a Tora scroll can no longer fulfil its function, due to wear or damage, it needs to be buried ritually. The scripture it contains, which is regarded a copy of the original scripture given by God to Moses, is sacred. A codex with the same text fulfils different functions and does not enjoy the same status. It was considered the more modern manuscript format, which is also easier to use, more suitable for study and reading outside the synagogue, and it also fulfils a quasi-philological function because of the masorah it contains.