"This Is About the Forest!"

An Early Medieval Collection of Laws

Philippe Depreux

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Texts.

SUB Hamburg

In early medieval Western Europe, legal diversity was widespread. At that time, the law did not yet apply universally to everyone in all parts of a kingdom. Instead, a person’s legal status depended on his or her origin. This meant that a Frank and a Saxon living in the same place were not necessarily subject to the same law. In court, a Frank’s case was judged according to the Lex Salica written in the early Merovingian period (late 5th century to early 6th century); in contrast, a Saxon could invoke the Saxon law established under Charlemagne (768–814), the victor over the Saxon peoples. For this reason, various legal texts, called Leges, had to be regularly copied and, if necessary, updated, such as the Lex Salica, which has survived in various versions documenting the adaptations of Frankish law to the new social and circumstances up to the early 9thcentury. This ensured that a judge could pass his sentence adequately.

Alongside these competing rights, Roman law had not lost its validity. Until the late 11th century, when the Corpus iuris civilis of Emperor Justinian (527–565) gained importance in the West, Roman law was known and repeatedly copied, especially in the form of the Codex Theodosianus, which was published in 438, and its variants (for example the Breviarium of the Visigoth King Alaric II in the early 6th century). The Church, whose legislation – called canonical law – rests on Roman law, played an essential role in preserving Roman legal practice. In addition to these various legal texts, regulations issued by the king also applied, which were usually deliberated during an imperial assembly and then made public. Some of these decisions and instructions took the form of an official letter, such as Charlemagne’s general exhortation (Admonitio generalis) from 789; many provisions, however, were simply handed down in more or less extensive articles (sometimes only as agenda items). Thus, they were called “capitularies” because these legal texts were written in concise paragraphs (capitula).

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Depending on the circumstances, such capitularies had a general or a time-limited or space-limited validity. Their transmission is diverse: they could be handed down individually or in smaller collections, with other legal texts, or with writings of other genres. Similar to the late Roman period, the law promulgated by the king was collected and transmitted in bundles in the Carolingian period. This was done by an abbot from what is now Normandy who, under Louis the Pious (814–840), arranged the capitularies of the emperor of the time and of his father and predecessor, Charlemagne, into a collection consisting of four books: the Capitularia Collection of Ansegis, which was almost immediately adopted as the official code of law.

Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

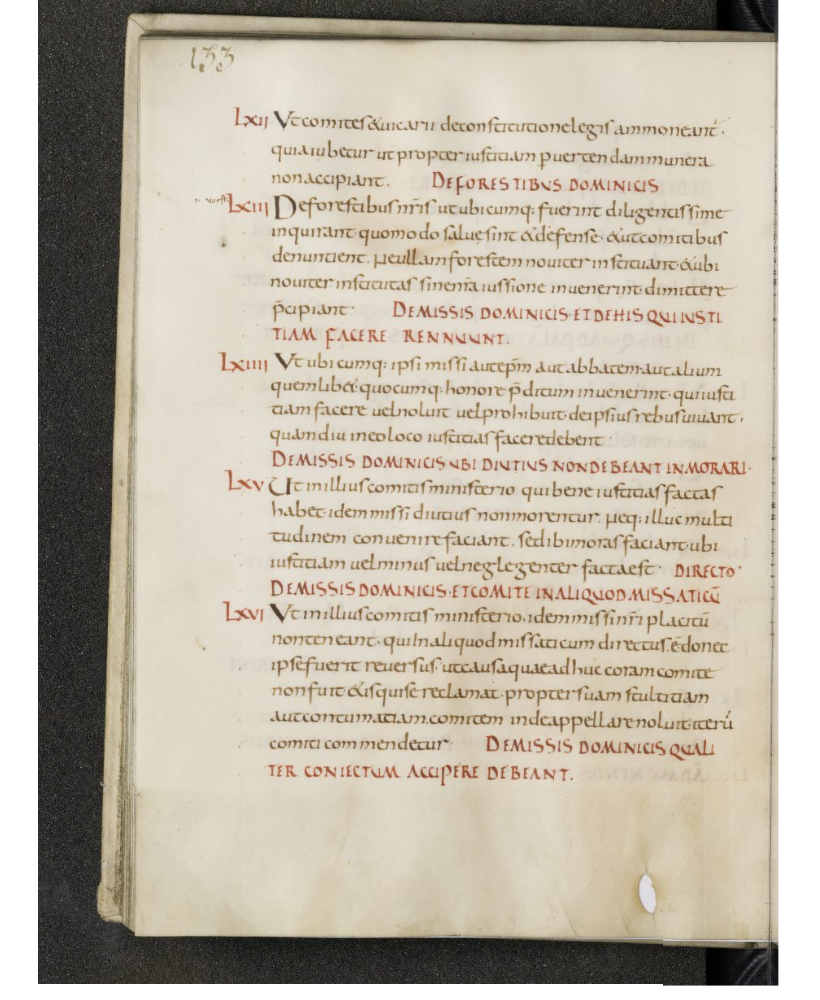

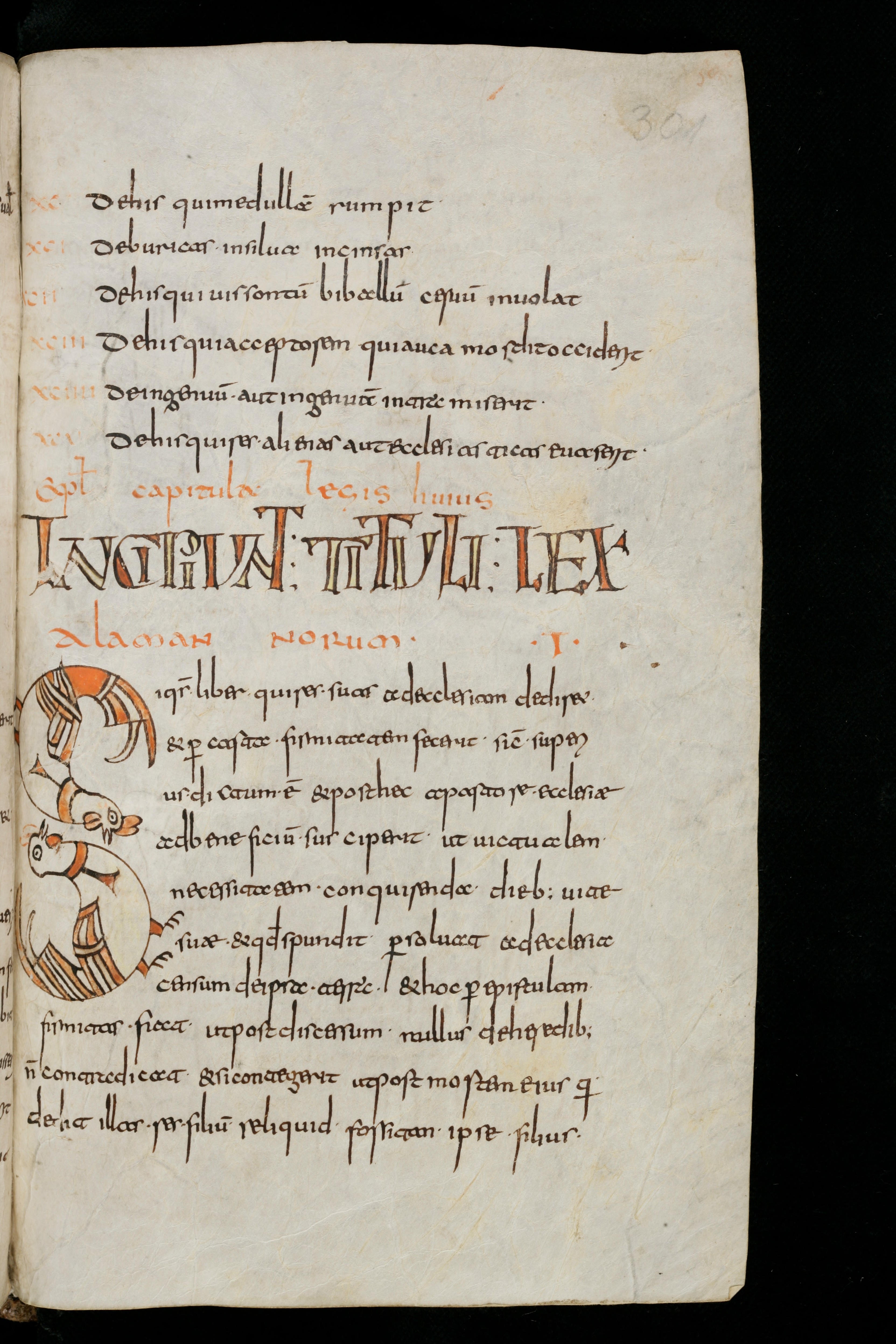

The Hamburg manuscript Cod. in scrin. 141a (so called because it used to be kept “in the cupboard”) documents this legal diversity. It was written in the eastern Frankish Empire in the second half of the 9th century. It may have originated in Corvey, where it was located in the Middle Ages, as can be inferred from the abbey’s late medieval ownership note. Judging from the palaeography, however, it was more likely produced in Fulda. Like many legal collections from the Carolingian period, it contains not only the capitularia collection of Ansegis and some capitularia from 829, but also various leges: two Frankish law codes (Lex Salica as well as the Lex Ribuaria) and an Alemannic law code (Lex Alamannorum). In the 10th century, a later scribe added further texts: after the capitularies, on the last, blank pages of the booklet consisting of four leaves (called quaternion) he copied some provisions from a collection of canonical law (the Collectio canonum Dacheriana) and at the very end of the codex a letter of Pope Gregory the Great (†604).

This very carefully written manuscript in a beautiful Carolingian minuscule, where the structure is clearly emphasised by rubrics (as usual in red ink), contains hardly any signs of use. However, it does indicate use by someone who may have wanted to make a passage easier to find. In the late 9th century, some Old High German glosses were entered. One of them, in the margin of Book IV, c. 63 of the Capitularia of Ansegis, is about a decree of Louis the Pious according to which the stock of all forests enjoying the special status of a royal forest must remain intact. To make sure that the user of the manuscript could find this passage more quickly, it was noted: This is about the forest! – i(d est) vorst!