The Palm-Leaf Manuscripts of Tamil Nadu

The Oldest Text in an Indian Language and a Monumental Tamil Grammar Book

Eva Wilden

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Texts.

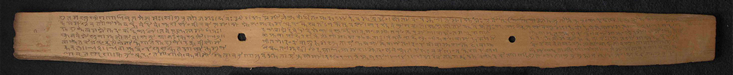

The manuscript Cod. Palmbl. I 1 from Tamil Nadu contains a text in Sanskrit, the ancient Indian cosmopolitan literary and scholarly language. It is written on the leaves of a palmyra palm and contains the first four aṣṭakas (RV 1.1–6.61) of the Rigveda Saṃhitā. The Rigveda is the oldest surviving text in an Indian language. Its exact age is unknown, but the generally accepted ‘date of convenance’ is around 1200 BCE.

The Rigveda is a collection of oral compositions dating back to a number of bardic priestly families. These hymns in ten circles of songs are addressed to various deities who were worshipped in the Vedic religion, the forerunner of Hinduism. Their language is an archaic form of Sanskrit. For more than a millennium, texts were passed down primarily orally from teacher to student, often from father to son. Schools developed sophisticated mnemonic forms of transmission to ensure that they were free from errors. Since the Veda is still considered a sacred text in modern Hinduism and some rituals still employ Rigvedic hymns, for example at marriage, there are still Vedic schools that teach recitation of the text or significant portions of it, although there is also evidence of writing on the subcontinent since about the 5th century BCE. An indication of the continuing emphasis on oral tradition is also the accents, relevant to the recitation, which can be seen in the manuscript at hand. The script used here is not Grantha, which is common in the South, but Nandinagarī, one of the North Norvidian scripts.

The first hymn, which is opened in the exhibition, is addressed to Agni, the god of fire, whose task is to take the offerings placed in the fire, such as milk and butter oil, to the gods in heaven.

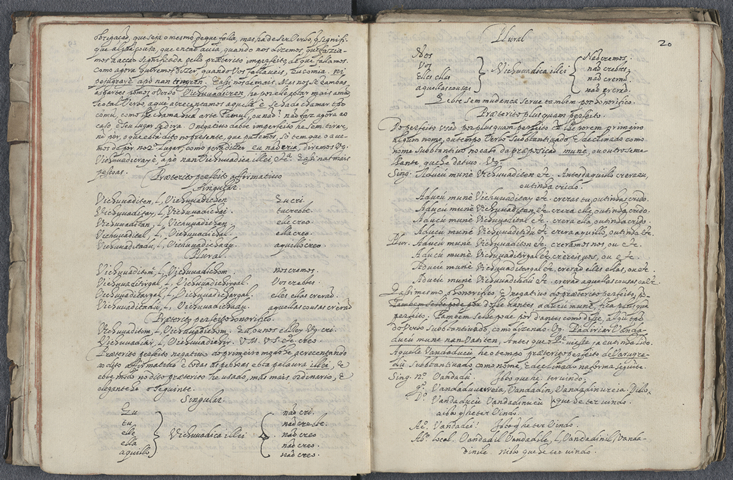

The 17th century paper manuscript Cod. orient. 283, ex libris Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach (1683–1734), has been in Hamburg since 1734. The paper is handmade and bound in leather. The handwriting – in black ink – is very elegant.

The title page has a Latin heading: “Arte Tamul Siue Institutio Grammatica Lingæ Malabaricæ”. The author’s name (Philippi Baldæj) appears in Latin, as do the place name and date (Jaffnapatam, that is Jaffna, 1659), together with a transcription in Tamil (பிலிப்பி பல்தெயுசு [Pilippi Palteyucu]) but with a different date (1665).

Philippus Baldæus (1632–1672), a Protestant missionary from the Netherlands, was employed by the Dutch East India Company to convert the Tamil communities in North Ceylon. He lived in Jaffna for almost ten years and also visited South India. In 1666 he went back to the Netherlands and published a monumental description, in Dutch, of South India and Ceylon (Naauwkeurige Beschrijvinge van Malabar en Choromandel, Amsterdam, 1672). The work was translated into German in the same year and also into English in 1703. The English edition contains an appendix entitled Introduction to the Malabar Language. Other works by Baldæus on the Malabar language are also known. Usually the south western coastal region of India is referred to as “Malabaric”, but Baldæus actually describes Tamil, which was spoken on the north western coast and is still spoken today.

The manuscript at hand appears to be an autograph of Baldæus with various works on Tamil written during his time in Ceylon. The language of description is Portuguese; this is not surprising as Baldæus may have had a Portuguese-speaking Tamil interpreter and also used grammars written by earlier Portuguese missionaries. In this manuscript, he mentions one of them, namely Gaspar Aguilar. Recently, doubts have been raised about the authorship of Baldaeus, who may have merely rewritten d‘Aguilar’s work for his own purposes.

The manuscript contains 75 folios; each measures approximately 18 x 21 cm. Some leaves at the beginning and end are not numbered. Covered are the Tamil script, declensions, and the verbal system. Interestingly, at the end there is also a “Confessionario Portuguez & Tamul” (pages 51–57), a kind of manual for confession, in which Portuguese sentences are translated into Tamil (in transcription). Another example of the pious purposes is an “Acto da contriccao” (act of contrition) in Tamil, both in transcription and in Tamil script.