A Real Mozart Manuscript?

Three Cadences in A Major

Oliver Huck

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Texts.

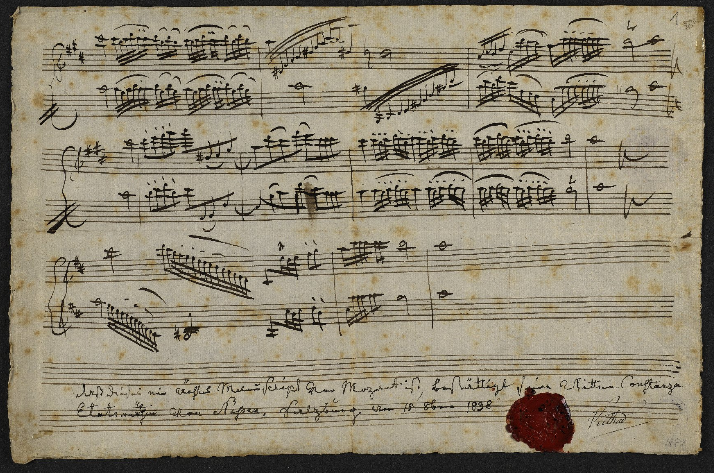

This sheet is an example of a Mozart manuscript that the composer’s widow Constanze declared “genuine” on 15 October 1838. It was long believed to be genuine and only later identified as in fact originating from Mozart’s father. Constanze writes: “That this is a genuine manuscript by Mozart is confirmed by his widow Constanza Etatsräthin von Nissen, Salzburg 15t 8ber 1838”. She also has her signature authenticated.

In the context of the original and the originator, this is not a forgery, and nor can it be assumed that Constanze was aware that it was in fact his father’s handwriting. The sheet was either sold or given away as a devotional gift; philological research by Wolfgang Plath was then able to clarify the scribe and authorship in 1960/61.

After the death of her husband Wolfgang Amadeus, Constanze Mozart (married to the Danish diplomat Georg Nikolaus Nissen from 1809) gradually sold or gave away the autographs from her husband’s estate. A valuable collection with many unprinted compositions was acquired by the Offenbach publisher Johann Anton André in 1799/1800. Many individual sheets, however, were instead scattered as relics, which Constanze provided with notes certifying the authenticity of her first husband’s handwriting. However, Mozart’s estate also contained quite a number of manuscripts that he had not written himself, and, since Mozart researchers were unable to distinguish Wolfgang Amadeus’s handwriting from his father Leopold’s up until 1960, Constanze must have acted in good faith when she noted on the sheet “that this is a genuine manuscript by Mozart, confirmed by his widow Constanze Etatsräthin von Nissen, Salzburg 15t 8ber 1838”. This signature with a seal was authenticated by the mayor of Salzburg on 17 February 1840. The Altona autograph collector Oscar Ulex would also have acquired the sheet in the belief that he now owned an autograph by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, paying little attention to the notes that it contained. Constanze gave a comparable sheet, written by Leopold and authenticated by her as being in (Wolfgang Amadeus) Mozart’s hand, to the London publisher Vincent Novello in 1829 (London, British Library, Add. 14396).

While compiling the New Mozart Edition, Wolfgang Plath then presented in 1960/61 a palaeographic study of Leopold Mozart’s manuscript that has since helped distinguish between the manuscripts of father and son. The three main criteria that he uses to summarise numerous details are, in Leopold’s case, a calligraphic ability, a neat and orderly handwriting that aims for legibility, and precisely drawn characters “with a tendency to pedantry”. Wolfgang’s handwriting, on the other hand, was not designed for good legibility, and Plath deems him “incapable of calligraphy”.

In addition to his own compositions, Leopold often copied those of his son. This he did in the early years in order to produce a legible manuscript of them in the first place, such as the very first piano pieces KV 1a–d written by his five-year-old son, which his father entered in the little music book that he had given his daughter Maria Anna in 1759 and that would then also serve to teach his son. Leopold helped to write out parts for performances in later years; the set of parts for the so-called “Old Lambach” Symphony in G major, K. Anh. 221/45a (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Mus. ms. 13467), for example, is a family production made in The Hague in 1766, in which Leopold and an unknown copyist were joined by Wolfgang’s sister Maria Anna, who wrote the bass part. There are also manuscripts that father and son wrote together, such as those of the first four piano concertos, the so-called Pasticcio Concertos K. 37 and 39–41 (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz Mus. ms. autogr. Mozart, W. A. 37. 39–41). Here, the father had his eleven-year-old son arrange piano sonatas by Leontzi Honauer, Hermann Friedrich Raupach, Johann Schobert, Johann Gottfried Eckard, and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach as concertos, and partly notated the piano part for them, finally making corrections in the orchestral part written by his son.

In the sheet kept in Hamburg, Leopold Mozart noted three alternatives for a cadenza in A major for two melody instruments. On the basis of the ambitus and since he himself was a violinist and vice-chapel master in the court orchestra of the Arch-bishop of Salzburg, it can be assumed that the notation is intended for two violins. There are no comparable cadenzas in his Gründliche Violinschule (1756), and nor did he himself or his son compose a concerto for two violins. The occasion and purpose of these cadenzas are thus unclear.