PhD Research SeriesUnveiling ConnectionsMedieval Greek and Georgian Written Artefacts as Witnesses to Liturgical Transformation

22 September 2025

How did Christianity spark the rise of written Georgian culture? In our PhD Research Series, Sandro Tskhvedadze explores the evolution of Georgian Gospel lectionaries and the pivotal legacy of George the Athonite in shaping liturgical traditions.

By Sandro Tskhvedadze

If the spread of Christianity in Late Antiquity can be seen as a major impulse for the creation of specific alphabets – and, more broadly, for the rise of literacy in various Eastern cultures – then several Caucasian languages, including Armenian, Caucasian Albanian and, in our case, Georgian, are no exception.

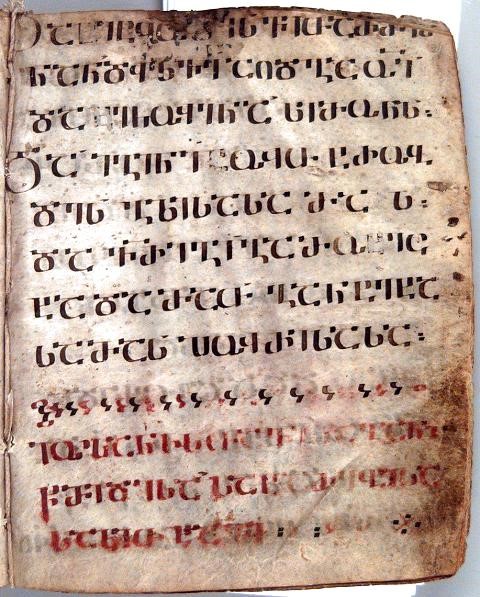

The adoption of the scribal culture for the Georgian language marked a significant cultural shift, paving the way for the development of a rich manuscript tradition. Predictably, the very first texts to be translated and produced were not secular but created for clerical use, reflecting the deep intertwining of faith, language and literary potential. Among these are one of the oldest surviving Georgian lectionary manuscripts and Old and New Testament books, all dating back to the fifth to sixth centuries.

Indeed, the production of codices and the spread of literacy were not an isolated effort that might have happened instantly. The process of translation and bookmaking unfolded in a vibrant, interconnected cultural space across distant places, namely, in the Georgian clerical communities within the Kingdom of Georgia as well as outside of it: from Jerusalem and Egypt to Asia Minor; and they were shaped by close contact with Greek, Armenian, Caucasian Albanian, Syriac and other cultural and linguistic traditions. As a result, these early Georgian liturgical books do not just reflect local practices; they offer a rare glimpse into the shared liturgical heritage of early Christian cultures, diverse in language but united in a common liturgical tradition. Within this broader cultural context, the first lectionaries, and some Gospel lectionaries among them, followed and reflected the ancient Hierosolymite system, which was one of the leading rites for the eastern churches.

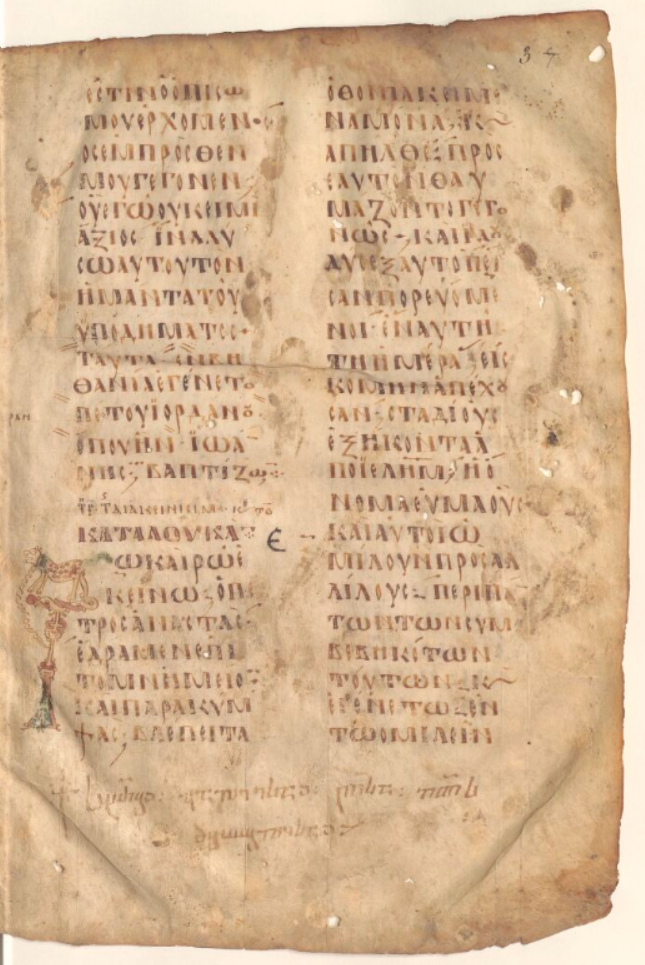

While the primary codices reflecting the early Jerusalemite system were undoubtedly Greek, most of them have been lost or survive only in fragments. This is where the significance of translated manuscripts appears on stage. These early translations – into Armenian, Georgian, Caucasian Albanian, Syriac and other languages – serve as vital clues, allowing us to reverse the process and piece together the original structure of the rite.

But the research does not end with reconstructing the Jerusalem rite – it also raises crucial questions: Was there a direct link between the ancient Jerusalem tradition and the later Byzantine rite, and do its Georgian counterparts reflect the divergence of both rites? This broad and complex issue leads to an even deeper, largely unexplored aspect of my research: How did these rites evolve over time? And what can a comparison of Georgian manuscripts – of different periods, from Late Antiquity to later Byzantine times – reveal about this transformation together with their Greek counterparts? Analysing the structure of Gospel readings and their arrangement within the ecclesiastical calendar, its cycles and commemorations, it is plausible to uncover patterns that shed light on how these sacred traditions were transmitted, adapted and reshaped across centuries within these two related written cultures, Greek and Georgian.

More intriguingly, Gospel lectionary manuscripts are more than just religious texts; they are silent witnesses to centuries of cultural and spiritual exchange and practices, holding the key to understanding how traditions were not only preserved but also redefined, developed and adapted for being used by local communities of diverse linguistical and cultural backgrounds. Unravelling this hidden history of two distinct written traditions sheds light on the dynamic exchange of ideas across these literary cultures and the peoples who practiced them.

As the rites evolved and new models were adopted – both in the original Greek and in Georgian translations and adaptations – the Byzantine system emerged as the most powerful and influential from the ninth century ce onwards. A crucial moment unfolded at Mount Athos, specifically at Iviron Monastery (literally the ‘Monastery of Georgians’), where Greek and Georgian liturgical practices converged at the end of the tenth century. It was here that a new harmony in Georgian liturgical tradition was born, reaching its most refined forms.

George the Athonite: Reshaping the Gospel Lectionaries

However, the adoption of the Byzantine rite was not an instant transformation – it unfolded gradually, step by step, starting with Euthymios the Athonite († 1028), the most prominent abbot of Iviron Monastery. As a result, Georgian liturgical codices captured various stages of this development, reflecting the evolving structure of Greek Gospel lectionaries along the way.

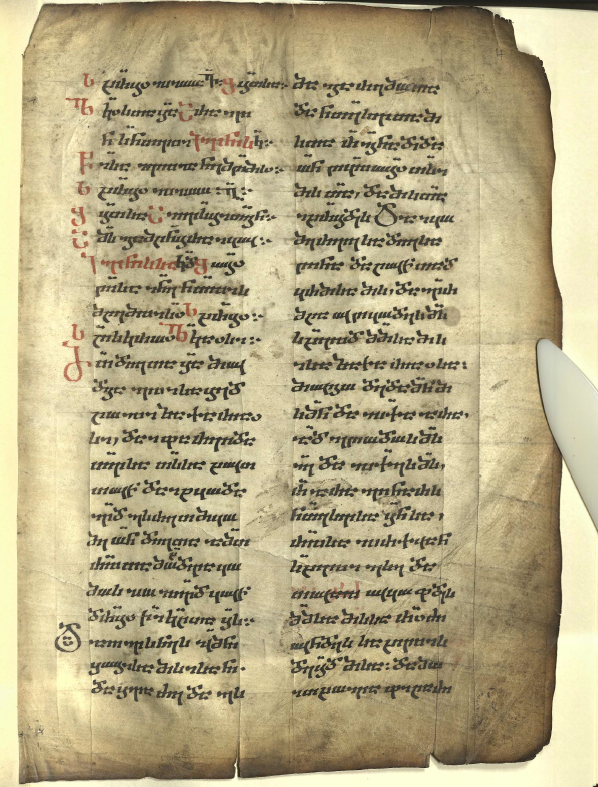

The translation and adaptation of the Gospel lectionaries are traditionally linked to George the Athonite, a subsequent abbot of Iviron Monastery. However, George was far more than a spiritual leader or solely a scribe or translator from Greek into Georgian – he played a major role in shaping and redefining the liturgical practices of Georgian clerical communities. His influence extended far beyond the walls of Iviron Monastery, reaching distant Georgian communities in places such as St Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai, Constantinople or Jerusalem, and well across the territories of the medieval Georgian Kingdom. George not only translated but harmonised the existing Byzantine monastic rule known in Georgian as berʒuli (literally meaning ‘Byzantine’) – adapting it to a new linguistic and cultural landscape. In doing so, he planted the seeds of a distinctly Georgian liturgical tradition, rooted in Byzantine foundations, yet its own.

As the abbot of Iviron Monastery (c. 1044–1056), George’s influence on Athonite worship was profound, leaving behind a legacy that continues to define monastic practice. Based on this, the books he translated, adapted and worked on include almost the whole spectrum of liturgical genres, from the rule for the monasteries (the Great Synaxarion) up to hymn-books and prayer books for daily usage, and among them also the Gospel lectionaries, which are in the scope of my project.

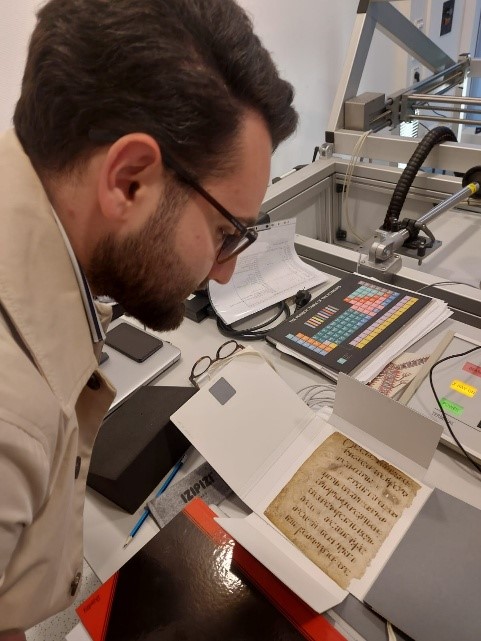

As a result of George the Athonite’s tireless work and his authority to adapt liturgical practices across Georgian monastic communities, the Gospel lectionary manuscripts bearing his redaction span from the mid-eleventh century to the later medieval period. However, these manuscripts are now scattered across the world, making it challenging to gather them into a single research corpus. They are housed in various repositories today, including Iviron Monastery on Mount Athos, St Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai, the Korneli Kekelidze Georgian National Centre of Manuscripts in Tbilisi, the Matenadaran in Yerevan, the Bodleian Library in Oxford and the British Library in London.

The diversity of their physical forms adds another layer of complexity. These lectionaries range from full codices to tiny surviving fragments – some once part of larger manuscripts, others repurposed as guard leaves in later codices. Their materiality is just as varied: from high-quality vellum to palimpsests whose older texts were carefully washed away and overwritten with the Gospel lectionary of the Byzantine rite, thus, revealing a fascinating story of adaptation, reuse and preservation.

Ultimately, the rapid transformation under George the Athonite’s scholarly and spiritual leadership reveals how swiftly and decisively Byzantine liturgical norms reshaped the Georgian monastic world. George, indeed, synthesised Greek sources not only for the community at Mount Athos but also for Georgian-speaking monastic circles in distant regions, wherever the traditions were spread.

His legacy is not merely one of adaptation but of transformation, leaving an enduring imprint on Georgian liturgical practices. In the end, George the Athonite’s work stands as a powerful testament to how the convergence of cultures – Greek and Georgian, Byzantine and local – can spark not only the preservation of tradition but the creation of something entirely new.

PhD Research Series

In this series of articles, PhD researchers from the CSMC Graduate School share insights into the themes of their work. All episodes will be published in Logbook, the CSMC blog. This is the final part of the series. An overview of all episodes published so far is available here.