PhD Research SeriesFrom Medieval Biblical Exegesis to Modern LinguisticsThe Legacy of a Forgotten Andalusi Scholar

9 September 2025

Centuries before modern linguists, Andalusi scholar Isaac ibn Barūn laid the groundwork for comparative Semitic linguistics with his pioneering 12th-century Judaeo-Arabic grammar. Carlos Jacobo Puga Medina introduces his influential work in our PhD Research Series.

By Carlos Jacobo Puga Medina

Imagine finding out that languages were already being studied with remarkable precision more than a millennium ago. In the Middle Ages, when everything was handwritten and there was no printing press, Jewish scholars compared Semitic languages (Arabic, Hebrew and Aramaic) and discovered their most distinctive feature: consonantal roots (Semitic verbs), which are composed of three (triliteral) or four consonants (quadriliteral). The most astonishing part? They were centuries ahead of today’s modern linguists and helped shape a linguistic tradition that, to some extent, remains alive in the teaching of Modern Hebrew today.

The exiled Jewish communities from Israel generally adopted the local language as a vehicle of communication, relegating Hebrew to the realm of synagogal life and liturgical poetry. Medieval Jews living under Islamic rule from the eighth century onwards, as was the case in al-Andalus (North Africa and Muslim Spain), used the Hebrew script (אבג''ד) to write Arabic.

This type of written Arabic is known as Judaeo-Arabic. Medieval Jewish scholars dedicated to the interpretation of the Scriptures played a fundamental role within the movement to revitalise the Hebrew language, since grammar in Semitic cultures was closely linked to the exegetical study of their sacred texts. The Bible was not only their holy book but also the collection of texts that preserved the Hebrew language in its purest form. As a methodology, they compared Hebrew etymologically with other Semitic languages to describe the grammatical rules and meaning of biblical roots. One of these brilliant minds was that of an Andalusi scholar, whom I am about to introduce.

Isaac ibn Barūn (twelfth century) was a Hebrew poet, grammarian and lexicographer from Saragossa (Spain), author of one of the most important works of medieval comparative grammar and lexicography, written in Judaeo-Arabic and entitled Kitāb al-Muwāzana bayn al-Luġa al-ʽIbrāniyya wa-l-ʽArabiyya (The Book of Comparison between the Hebrew and Arabic Languages). Sources agree in pointing out that Ibn Barūn belonged to a noble family. Most of the limited biographical information we have about Ibn Barūn is available through the poems of his contemporaries, especially his friends, the great Hebrew poets Moshe ibn Ezra and Judah ha-Levi, who addressed him with honorific titles such as nagid (leader), nasiʾ (prince), sar (minister) or ṣāḥib al-shurṭa (commander of the police). Ibn Barūn sent a copy of his Kitāb al-Muwāzana to the former, and a basket of almonds, raisins, figs and citrons from Malaga to the latter. Similar to most Jewish scholars at that time, Ibn Barūn’s educational background is extensive, encompassing both Jewish and Arabo-Islamic traditions. Evidence of his excellent education is reflected in his seminal treatise on comparative grammar accompanied by a Biblical Hebrew dictionary, the Kitāb al-Muwāzana, which has survived incomplete.

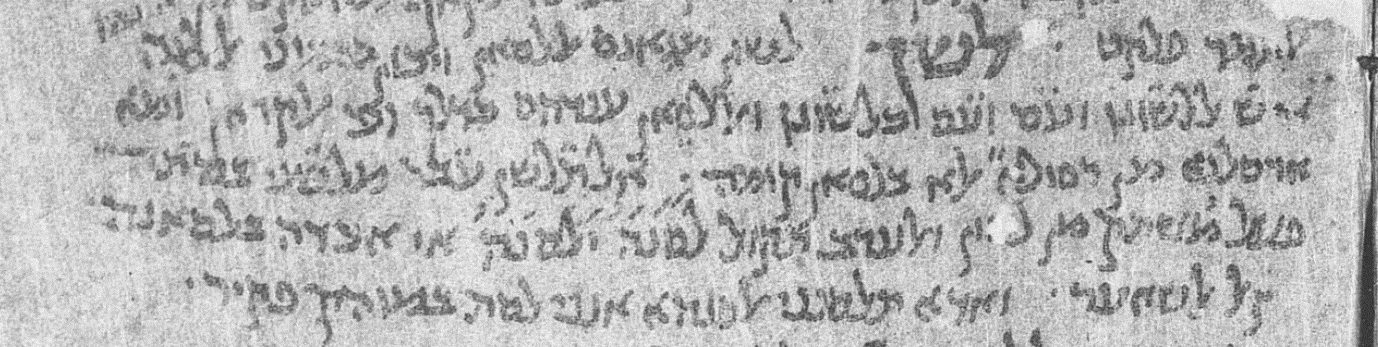

The following entry is taken from his dictionary to illustrate his method, enriched by biblical and Qur’anic verses and classical Arabic poetry, where lamed-shin-nūn is a triliteral root expressing everything related to ‘tongue’ and ‘language’ in both Hebrew and Arabic. Amazingly, despite being nearly 900 years old and reading from right to left, it looks like an entry in a modern dictionary!

lamed-shin-nūn

לשון (lashon) is similar to لسان (lisān), ‘tongue’ and means language like איש לשונו (Genesis 10,5) and ועם ועם כלשונו (Esther 3,12; 8,9). Lisān in Arabic means the same according to the Qur’ān: “وما أرسلنا من رسول إلا بلسان قومه” (Surah 14:4 “And We did not send any messenger except [speaking] in the language of his people”). אל תלשן עבד (Proverbs 30,10), מלשני בסתר (Psalms 101,5) are verbs derived from lashon. The Arabs say: «لسنه يلسنه» (lasanahu yalsunuhu), meaning he slandered him with his tongue. The poet [Ṭarafah] said: «when their tongues slander me I am neither contemptible nor destitute».

By way of background, the doctoral thesis of the Russian orientalist Pavel K. Kokovtzov marks the starting point for the rescue from oblivion of Ibn Barūn’s Kitāb al-Muwāzana. Kokovtzov’s edition was published in 1893 and was the first critical edition based on an incomplete manuscript preserved in the Russian National Library, which houses one of the world’s richest collections of Judaeo-Arabic manuscripts, known as the Second Firkovich Collection.

Today, the medieval Jewish legacy is being recovered and studied in its various scientific and literary manifestations, using modern methods, at leading international academic centres, such as the University of Cambridge, the University of Granada, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the University of Hamburg. Ibn Barūn should not be neglected in this recovery task, as his work is considered, to some degree, as the pinnacle in the comparative study of Semitic languages. For this reason, I think that it is important to keep studying Ibn Barūn’s legacy in its historical context to better understand the impact and value of his contributions. Actually, the research project on which I am working has two main goals: firstly, to carry out a linguistic study of the Kitāb al-Muwāzana, covering all parts of grammar, i.e. phonetics, morphology, syntax, and semantics; secondly, to identify the codicological and palaeographical characteristics of the previously mentioned manuscript and its main Judaeo-Arabic sources for comparative purposes.

PhD Research Series

In this series of articles, PhD researchers from the CSMC Graduate School share insights into the themes of their work. All episodes will be published in Logbook, the CSMC blog. This is the 7th part of the series. An overview of all episodes published so far is available here.