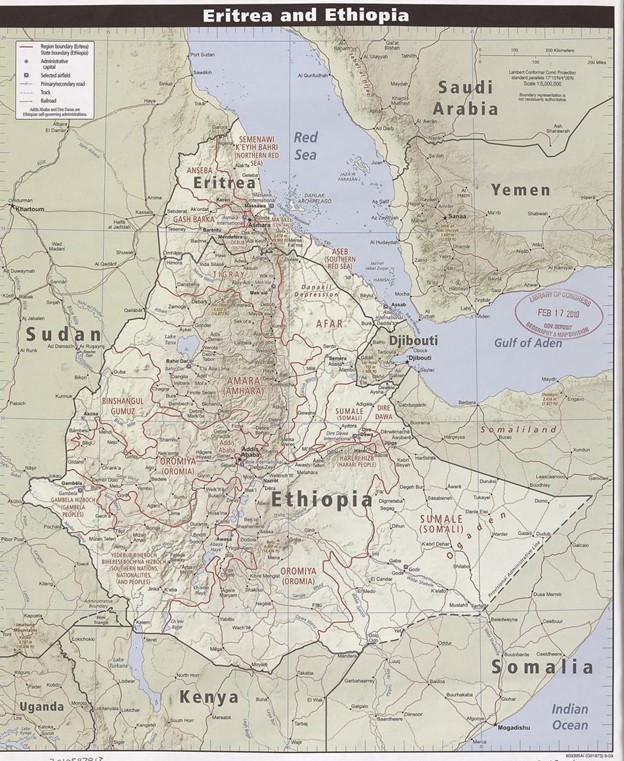

PhD Research SeriesEphemeral Libraries and Everlasting ListsOrganising and Preserving Knowledge in Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea

25 August 2025

The desire to create lists connects people across continents and centuries. What makes these documents so fascinating? Doctoral researcher Michael Hensley, who studies Ethiopian and Eritrean book lists, reflects on the significance of these special written artefacts.

By Michael Hensley

Humans have a natural propensity to perceive patterns and create order. Accordingly, we really like lists. In fact, our inclination to make them is so pervasive that websites, notebooks, and even our minds are inundated with different types, including rankings, to-do lists and bucket lists. Additionally, the go-to method of proving something is often to supply a list, which should provide a dazzling array of supporting evidence – ironically, this also seems to be the case when the argument is that humans love lists!

Given that lists are so ubiquitous, why are we so eager to make them? One reason is to get things done, as to-do lists illustrate wonderfully. Another is to describe that which is indescribable or to imbue seemingly mundane entities and phenomena with special importance, thereby ordering and making sense of a world that is so disorderly. Finally, I cannot help but agree with Umberto Eco’s evaluation that ‘we like lists because we don’t want to die’; there is truly something irresistible about the potential, albeit illusory, ‘infinity’ of lists.

We, the list-makers, and most of the things that we record will inevitably perish. Yet, what sometimes survives are the lists, stored away in notebooks and computers or on sticky notes and calendars. Since they are purposeful creations, these enduring documents can tell future generations a lot about us, including how we made sense of the world, what we valued, and what we hoped to accomplish with the limited time that we had. Thus, lists can be surprisingly informative, as the many projects and books on different types of lists in recent years have demonstrated quite convincingly.

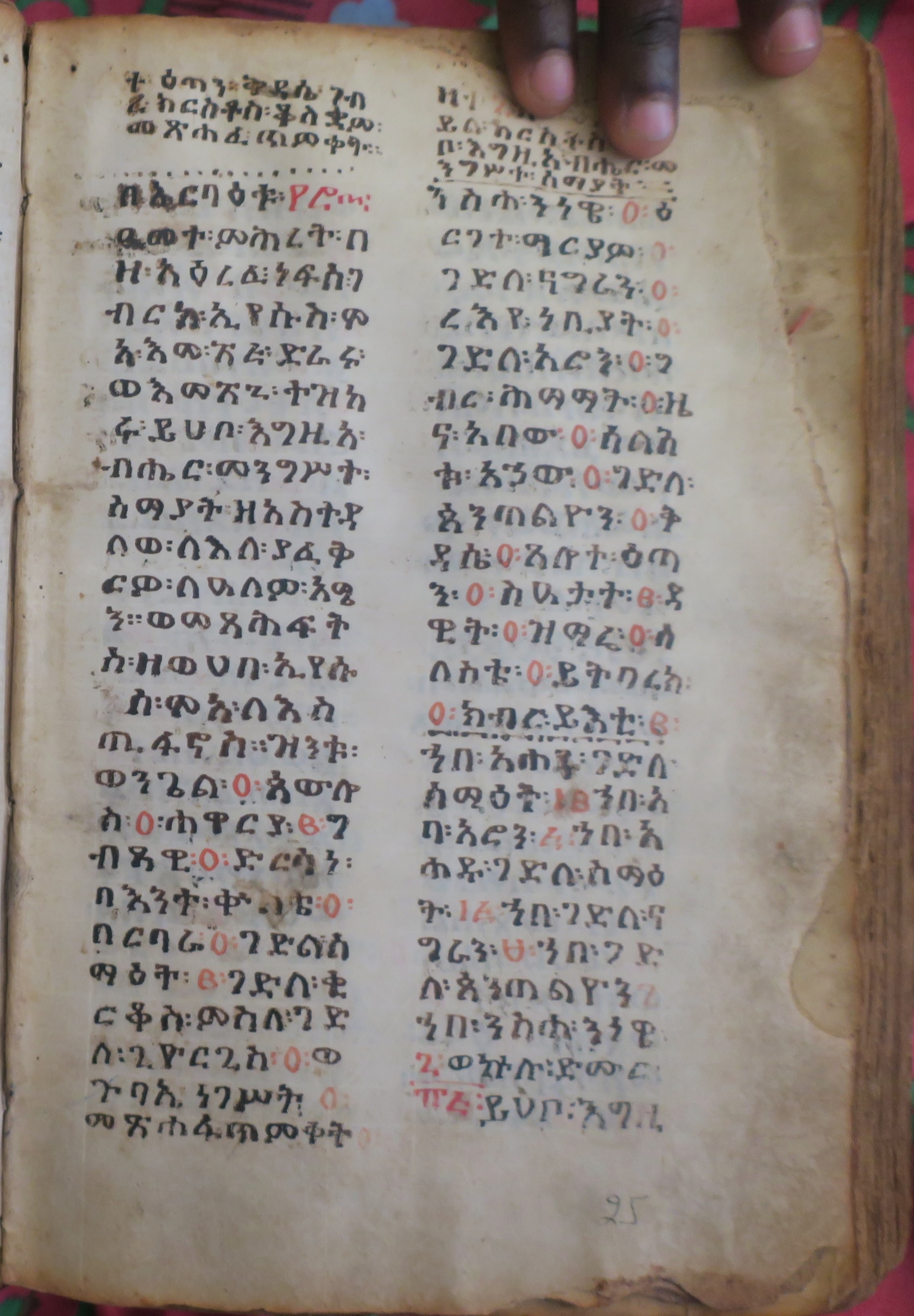

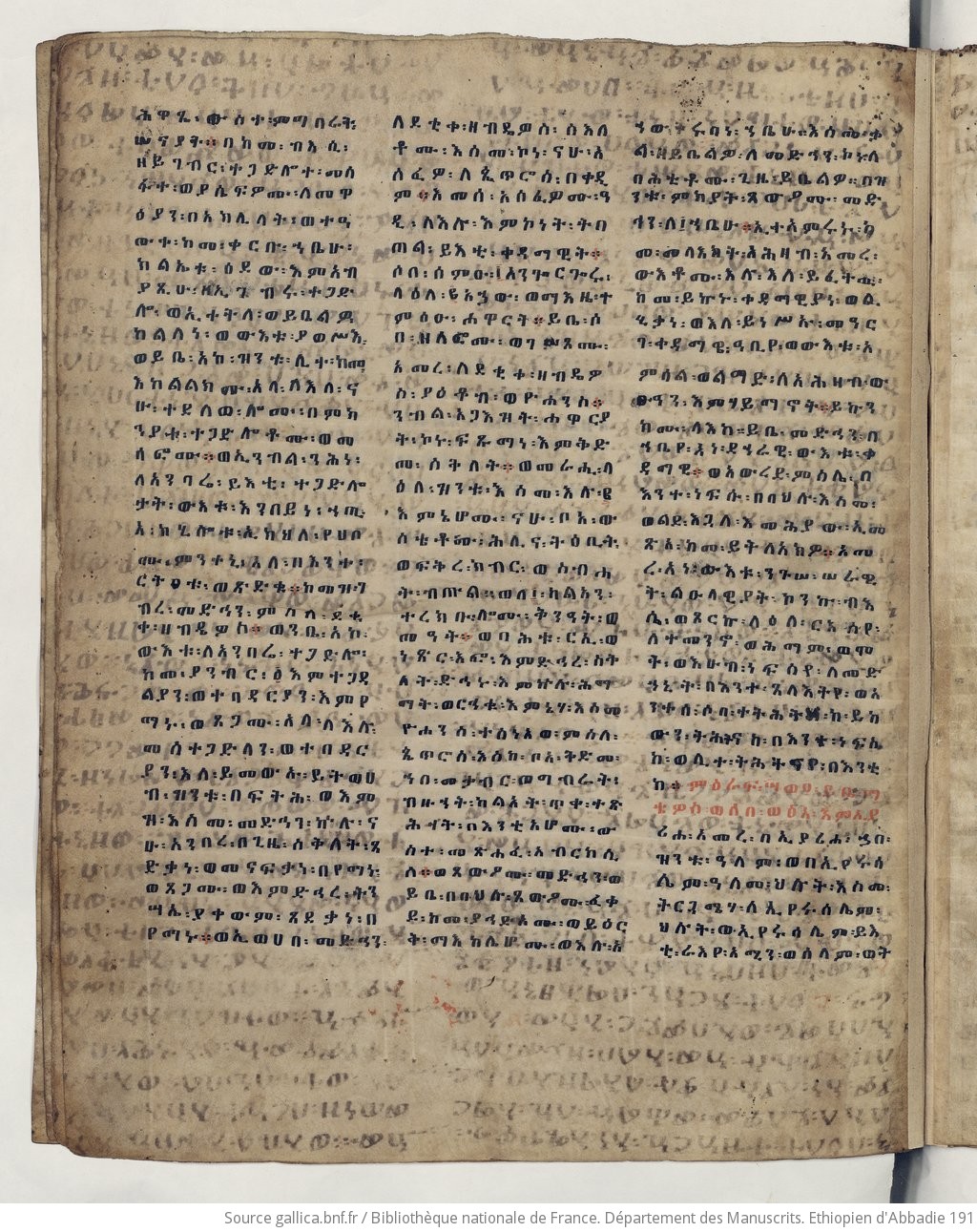

My own research contributes to these ongoing list-related discussions by focusing on Ethiopian and Eritrean booklists, especially those from the medieval, or early Solomonic, period (c. 1270–1543). Written in Gəʿəz, the administrative language of the Solomonic Empire until Amharic began to replace it gradually in the sixteenth century, these documents are most often found in the blank spaces of gospel manuscripts. Despite usually taking up less than a page, they are incredibly rich, replete with different inks, numerous types of punctuation and conjunctions, numbers, and the names of people, places and, unsurprisingly, manuscripts. These individual elements work together to either record book donations or inventory monastic or church libraries.

Ethiopian and Eritrean booklists offer many avenues for research, but two have been particularly fruitful for me. The first is their value for reconstructing material evidence. Although an impressive number of Ethiopian and Eritrean manuscripts is extant, the vast majority postdate the fifteenth century. Meanwhile, even still extant medieval witnesses can only say so much about the libraries of which they were once part, since they often serve as the sole, or one of the few, surviving witnesses to them.

Because booklists were usually meant to record all manuscripts from donations or those belonging to a monastery or church, they offer an unparalleled glimpse into the size, contents, and growth of long-lost libraries. Accordingly, this has allowed me to investigate a host of questions that would otherwise be unthinkable, including what the standard medieval library was like or how different collections changed over time.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Manuscrits, ms. Ethiopien d’Abbadie 191, f. 96v. Gallica. Accessed 20 August 2025.

Medieval Ethiopian and Eritrean booklists should already merit attention for what they archive. However, they offer so much more than just this. They can tell us, for instance, the names of manuscripts and show how similar ones were referred to differently across regions and time; conversely, they also reveal that quite different manuscripts could share the same name. Moreover, since there is no single, standardised way of presenting a list, the ways in which different communities did so reveal a great deal about their views on the purpose and value of their books. The placement of some manuscripts, for instance, can tell us whether or not they were part of the biblical canon at one point in time, as Ted Erho has done with the Shepherd of Hermas (Erho, ‘The Shepherd of Hermas in Ethiopia’). Or, to give another example, the order of lists can help us identify when a particular manuscript superseded another, as I do in my dissertation. Thus, a significant part of my research is not just analysing what these booklists say, but how they do so.

The most satisfying aspect of research on booklists for me is not the books, although this certainly has its charms. Instead, what I find most fulfilling is the opportunity to engage once more with medieval Ethiopian and Eritrean communities that would otherwise be lost. Through these lists, they hoped to ensure that their donations would be remembered and their libraries would last forever. Little did they know, they also left behind a piece of themselves.

PhD Research Series

In this series of articles, PhD researchers from the CSMC Graduate School share insights into the themes of their work. All episodes will be published in Logbook, the CSMC blog. This is the sixth part of the series. An overview of all episodes published so far is available here.