PhD Research SeriesHow Books Shape Social Practices

11 August 2025

In 19th-century Damascus, Khālid al-Naqshabandī builds a library that becomes a centre for scholarly exchange. Later, its preservation requires legal ingenuity on the part of his heirs, until it is eventually scattered around the world. In our PhD research series, Joud Nassan Agha tells its story.

By Joud Nassan Agha

We often overlook the profound significance of physical books – their unique material presence and cultural value – in a world now dominated by e-books and digital libraries. As a historian, I am particularly interested in a time when books made of paper were cherished and seen as important treasures that shaped societies and cultural practices.

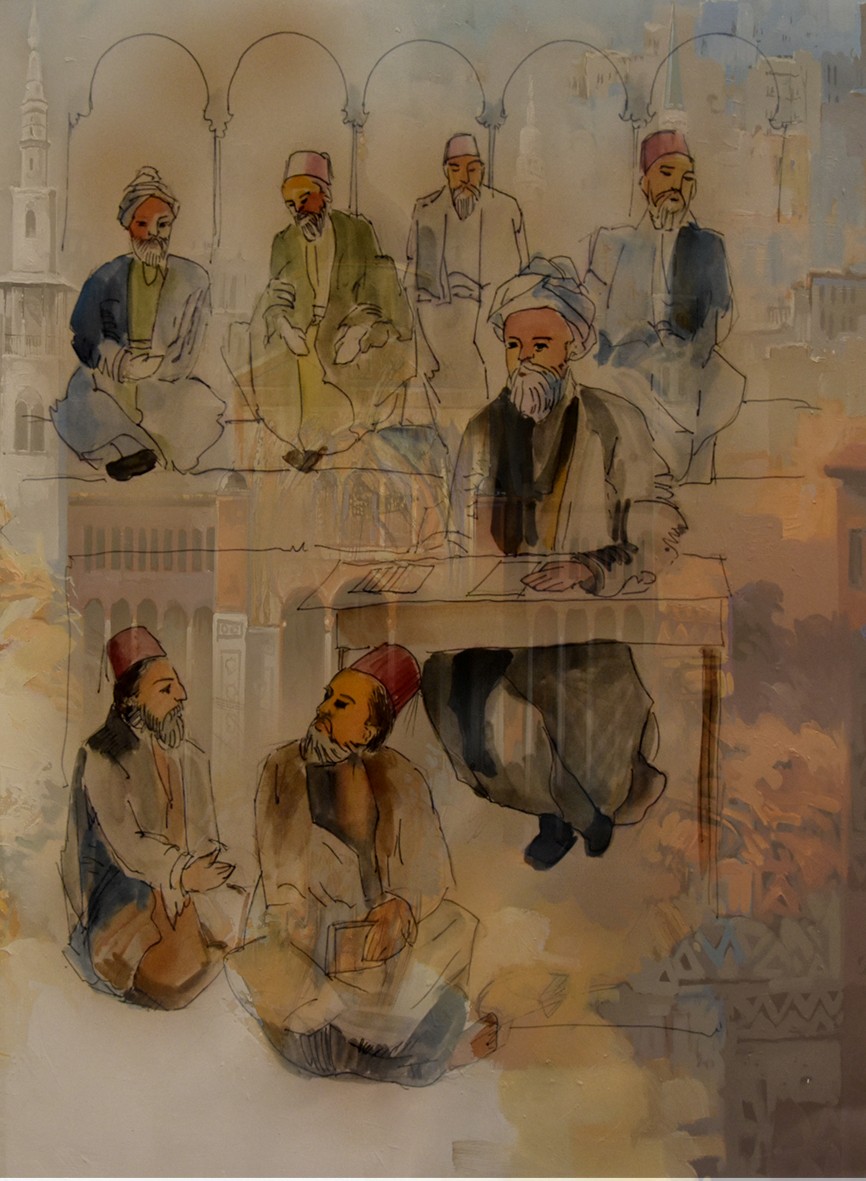

My project takes us back to early nineteenth-century Damascus, telling the remarkable story of a library belonging to a man named Khālid al-Naqshabandī (d. 1242 AH/1827 CE). Khālid was a Sufi and a mystical leader whose life was closely connected to the world of books. He was born in a small village on the borders of the Ottoman and Iranian empires in modern-day Iraqi-Kurdistan. Over time, Khālid became a well-known religious figure and the founder of a Sufi order that attracted thousands of followers across the Ottoman Empire, Iran and beyond. When he was 31, Khālid embarked on a long journey to India, meeting numerous scholars. This journey marked the beginning of his library’s foundation, as he attended various religious and intellectual gatherings, soaking up knowledge and collecting books. Upon his return to Iraq, Khālid became a teacher and preceptor in colleges (madrasas) in al-Sulaymāniyya and, later, in Baghdad. During this time, his library was enriched as he was exposed to different intellectual milieus where books were produced, copied, circulated and acquired.

Finding a New Home!

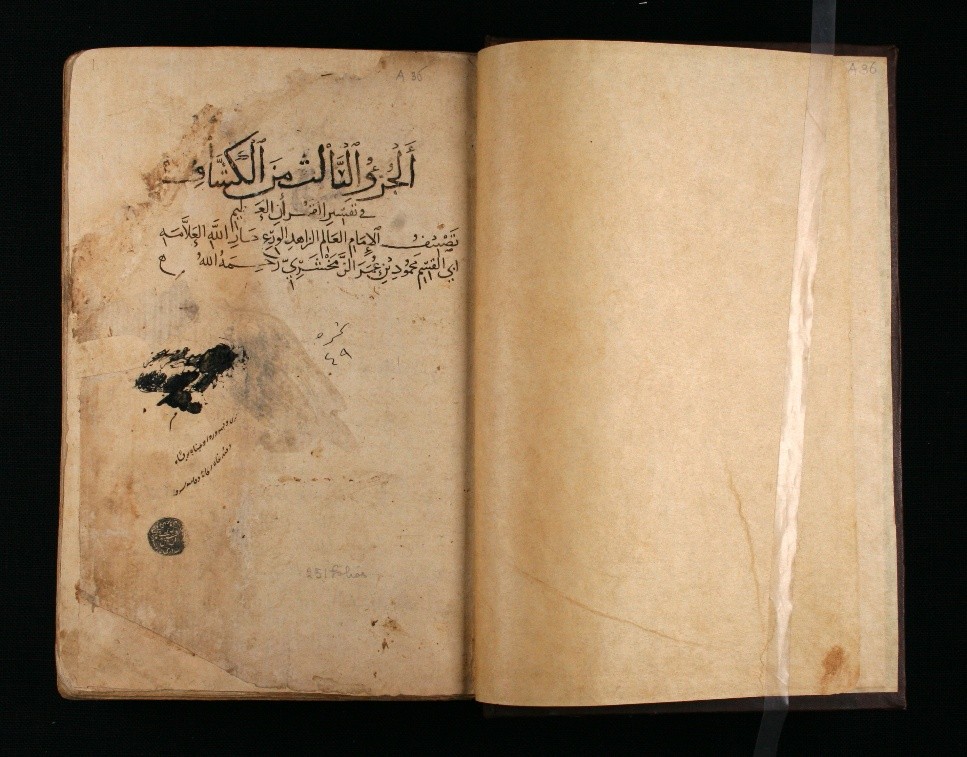

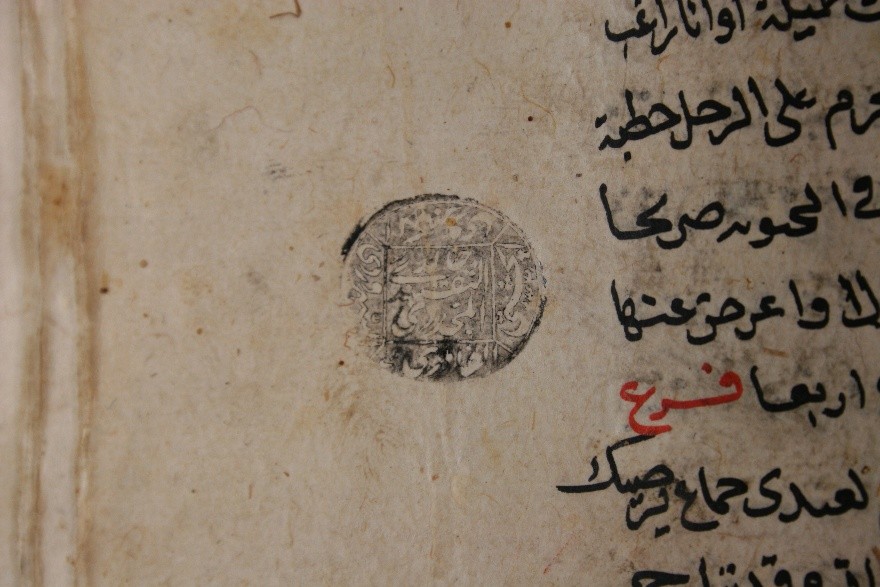

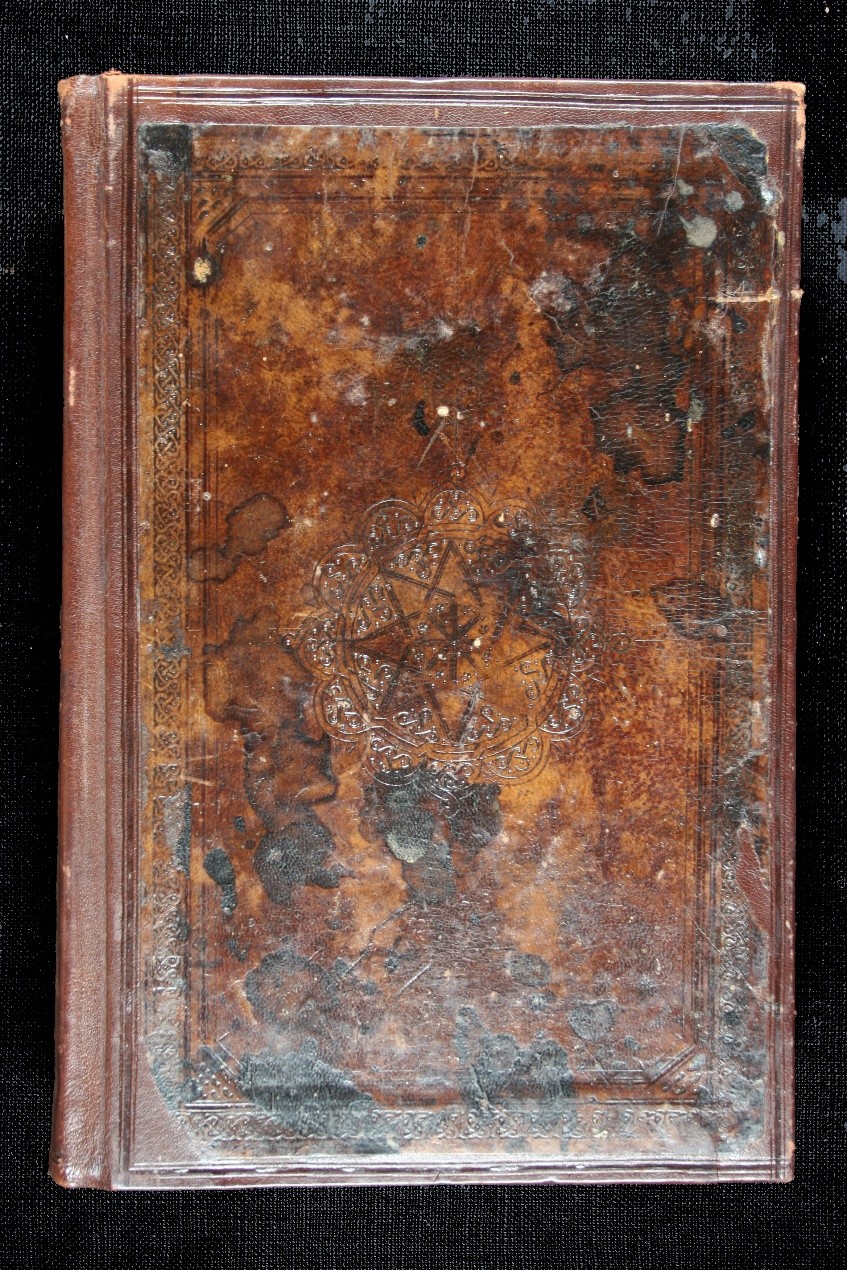

When Khālid was about 45, he decided to move to Damascus where he settled for the last four years of his life in order to spread his Sufi order and engage with prominent scholars in the city. He brought his valuable collection of over a thousand books and created a library within his new house, which also included a madrasa. This practice of relocating such a large collection of books represents one of the social practices related to the value of books, viewing them as worthy property that needs to be transferred. Within the story of my project, I want to tell you more about this social practice of the books’ translocation and their implications. These social practices are embodied in what we call ‘documentary notes’, written into these books by individuals who used them in various contexts. These notes serve as our windows into different social contexts, thereby, understanding the books’ dynamics and practices related to them, such as owning, endowing, lending, borrowing, reading, learning, teaching and copying.

Endowing Books and Strategies of Preservation

When Khālid had already settled down and started teaching and interacting with the Damascene scholars, his library began to take a central position in his life and probably also functioned as a teaching curriculum. This idea is based on my primary analysis of the inventory of Khālid’s library, which has fortunately come down to us in the form of a manuscript now housed in the National Library of Damascus. Analysing this inventory helps us to understand what Khālid’s library was like and gives us a glimpse of the intellectual life in Damascus in the early nineteenth century.

While the library’s position during Khālid’s lifetime was significant, his decision shortly before his death to ensure its preservation for future generations through endowment was equally important. Khālid aimed to protect this cultural capital from potential division after his death by establishing it as a family endowment. To endow a property means to make it a permanent charitable donation that cannot be sold or transferred. This socio-religious practice of endowing libraries to preserve them is another intriguing aspect of the story, illustrating the strategies employed to maintain books in their original locations, thereby, preserving the functions they once served.

A Fictional Dispute or a Real Conflict

Nearly thirty years later when Khālid’s son passed away, the tale takes a surprising twist, marking the loss of the last official overseer of the endowment. Khālid’s widow and his son’s widow found themselves in a difficult situation: They were afraid of not being able to preserve the library after the death of the last legally appointed overseer. Their solution was a common legal practice of that time: They decided to go to court to secure the library’s status as an endowment by obtaining a legal document with a verdict reaffirming its status. To do this, they needed a legal case – a plaintiff, a defendant and witnesses. They created a fictional dispute about whether the library should be included in the inheritance or remain an endowment. This court case ultimately led to a verdict that confirmed the endowment’s legality. Interestingly, these legal proceedings were recorded in the aforementioned manuscript under the library’s inventory, helping us to understand the legal practices surrounding books and methods of preservation.

Tracing the Fate of Khālid’s Library

The last chapter of our story is the fate of the library, which is illustrated by the number of books which have been identified that once belonged to Khālid. Despite the strategies followed to preserve them in their original situ and context, Khālid’s books became scattered all over the world. I was able to identify some of his books dispersed in many European and Middle Eastern libraries through endowment statements and seals imprinted on Khālid’s books. This last aspect of the story also points to another social practice linked to the dynamicity of books: their movement and distribution within different book collections. This raises a question: How did these endowed books find their way to libraries throughout the world after having a legal document to ensure their preservation?

Telling the story of how each book not only contains a text, but is also an object of cultural heritage and a testament to the enduring power of materialised knowledge that shapes our history is an adventure. I invite you to join me on this journey as we explore the story of Khālid al-Naqshabandī’s library and the fascinating world of his books.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank my father, Naser Nassan Agha, for creating these illustrative pictures for the story of Khālid and his library, and for his willingness to limit his artistic imagination and adjust to my simple vision

I would also like to thank Moya Carey, Curator of Islamic Collections at the Chester Beatty in Dublin, for providing me with these high-resolution pictures of Khālid’s manuscripts located in the Chester Beatty.

PhD Research Series

In this series of articles, PhD researchers from the CSMC Graduate School share insights into the themes of their work. All episodes will be published in Logbook, the CSMC blog. This is the fifth part of the series. An overview of all episodes published so far is available here.