PhD Research SeriesHeadaches? Plagued by a Jinn? In Love with your Neighbour’s Wife? I Have a Spell for That!

30 June 2025

In West African manuscript cultures, written artefacts were produced to address all kinds of life problems, offering their owners relief if used correctly. PhD researcher Jannis Kostelnik investigates what these manuscripts can tell us today about the lives of their owners and colonial history.

Henry Solomon Wellcome, the British-American pharmaceutical entrepreneur, was a curious man of many interests, which ultimately led him to accumulate an eclectic collection of not only all things medicinal, but also arms and weapons, antique collectibles in general, and books. The author Frances Larson remarked in her book An Infinity of Things that ‘Wellcome’s desire to collect was not unusual, but his ability to pursue that desire so zealously set him apart’. Indeed, Wellcome himself described his collection as a ‘warehouseful, in quite indescribable disorder’.

Within this indescribable disorder – nowadays luckily neatly catalogued, curated and partly made available to the public in the Wellcome Collection – a corpus of six West African medico-religious composite manuscripts has hitherto laid dormant, waiting for a researcher to reveal their secrets.

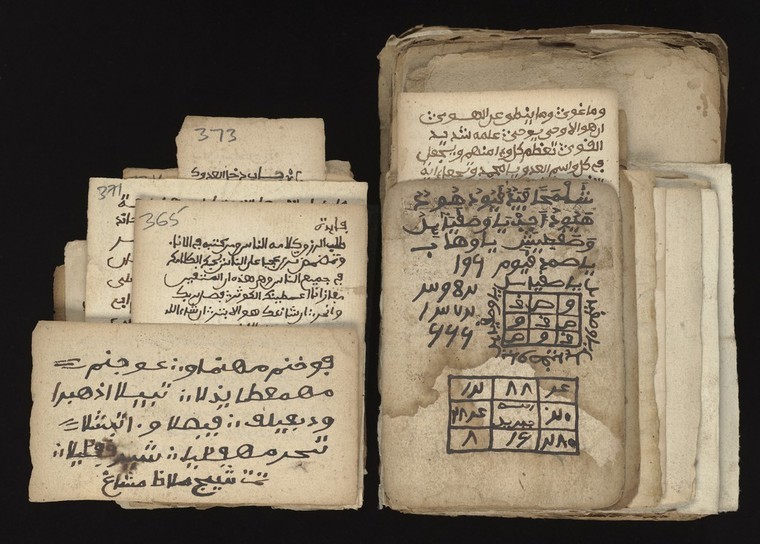

Now, before we delve into the manuscripts’ contents, what does ‘medico-religious composite manuscript’ actually mean? Let us begin with the term ‘composite’: A composite manuscript is a collection of documents that were formerly independent but subsequently conjoined or bound in a single manuscript. These do not necessarily have the same authors or were produced at the same time, but they still ended up in the same manuscript. Some of the West African manuscripts in the Wellcome Collection take this to an extreme level, as can be seen from the wealth of different hands and formats in the photo below.

Medicine for the People

And ‘medico-religious’? Well, this is where it gets complicated. Manuscripts such as the ones I research are often called medico-religious because they provide recipes for cures against different illnesses, often employing plant medicine. They also always contain verses from the Qur’ān, hence the term ‘religious’, and are often headlined fāʾida (Arabic for ‘usefulness, benefit’). However, the topics include much more than what we in the West usually understand as ‘medicine’. Alongside recipes against headaches, worms or menstrual pains, there are those on how to counter a lack of fish in your river, make it rain, get rid of those pesky Jinn that may haunt your thoughts or those of your loved ones, and even some more spicy ones. You can, for example, find recipes that are said to make a couple separate, often to make way for the user of the spell to marry one of the former partners. These manuscripts are basically reflections of ‘folk medicine’ employing local cures and Qur’ānic verses, and which – unlike more elite recipe books that employ ingredients completely unavailable to most local actors – can be carried out by everyone, no matter their societal status.

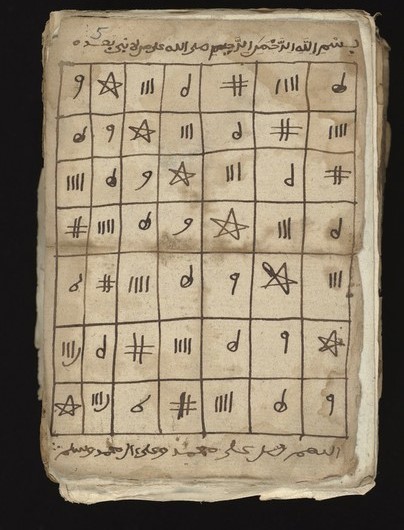

Looking at the recipes, we can, indeed, see that all walks of life were represented: Recipes with hardly legible handwriting and lots of orthographic mistakes were probably written by people who did not write often and had only a basic education in the Arabic language and script. On the other hand, when we find recipes that were written in elegant calligraphic hands, quoting extensively from the Qur’ān or the Ḥadīṯ – collections of quotes and deeds of the Prophet Muhammad – and which employ complex figures from the popular grimoires of Aḥmad al-Būnī, we can guess that their authors were more highly educated.

The Crucial Issue of Magic and Whether It Is Good or Bad

Wait, grimoires? Are not grimoires books of magic? Well, yes, but in the Islamic tradition, what Westerners understand as ‘magic’ is often considered a science – one of the ‘hidden’ or ‘esoteric’ sciences – and is fully accepted as a scientific process. Siḥr – the literal translation of ‘magic’ in Arabic – is bad, however, and the goal of these recipes is often to counter any bad siḥr. Take, for example, geomancy: This is a highly complex technique of ‘fortune-telling’ by drawing lines into the ground – not randomly, but following certain precalculations. Eventually, you end up with certain figures associated with different prophets, lunar mansions, plants, elements, cardinal directions… To answer the question you asked, you have to know how to interpret the figure and which of the associated categories is important for the question you asked. It is a little bit like reading the alethiometer, the ‘Golden Compass’ in the film of the same name. It is not hard to guess why people conceived of this complex process, which is often found in the manuscripts I research, as a science.

Overall, these manuscripts, though often inconspicuous, can tell us a lot about the backgrounds of their owners, such as their level of education and the languages they used in writing. Most importantly, however, they tell us about the kind of problems they had, what hurt them or otherwise made life difficult for them, and then, on the other hand, how they tried to counter and overcome these problems.

Origins and Entanglements

Regarding the Wellcome manuscripts, they are fascinating because they represent the same genre, but come from two different corners of West Africa, Northern Nigeria and Senegambia (marked in green on the map below).

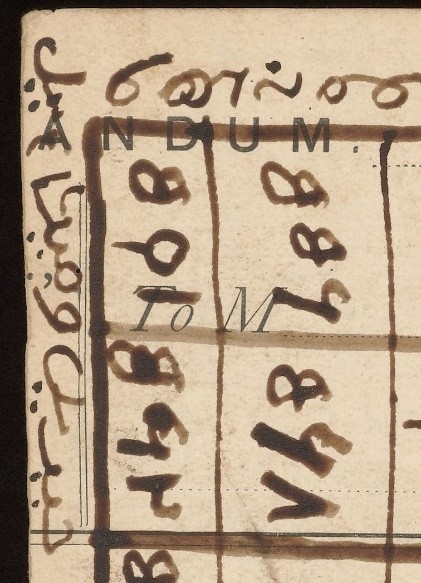

Thus, they make it possible for us as researchers to find out parallels and differences in the same genre between two different regions. On the other hand, the paper used in the manuscripts is partly ‘recycled’, that means it was actually produced for a different purpose, often associated with the colonial governments in the region: One folio was originally part of a memorandum book, some seem to be taken out of ruled notebooks, yet others come from guides on penmanship used for teaching Latin cursive handwriting.

These European entanglements are not only visible in the materiality of the manuscripts but also in their content. In one manuscript, we find an amulet containing gun-shaped drawings, which was supposed to protect the bearer in war, while another, particularly portable, manuscript designates itself as an instrument of ‘protection for the Jihad against the Infidels’, which probably alludes to the ever-advancing colonial forces during the ‘Scramble for Africa’.

By, thus, metaphorically and literally reading between the lines and looking behind the texts, we can reconstruct the colonial trajectories that intertwined with these manuscripts, which ultimately led them to be taken from their place of origin and out of their status as protective or even powerful objects. They were relegated to the status of ethnological curios in Europe, sold by auction houses and, finally, ended up stored in a London collection.

PhD Research Series

In this series of articles, PhD researchers from the CSMC Graduate School share insights into the themes of their work. All episodes will be published in Logbook, the CSMC blog. This is the second part of the series. An overview of all episodes published so far is available here.