A Textbook Example of Medieval Sword Fighting

22 April 2022

The oldest surviving instruction book on sword fighting in Europe is still being used to learn this art today. 'Royal Armouries Fecht1' not only taught Cornelius Berthold how to hold the weapons, but he also learnt a lot about the manuscript itself, which is still raising questions to this day.

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Artikels

If you want to repair your car yourself, do your tax return or learn how to survive out in the wilderness, there are countless videos on YouTube these days that will show you how to do it. A few years ago, though, people were still consulting ‘how to’ guides in book form. Practical guides of this kind have actually been around for centuries. One such example is a medieval manuscript now known as Royal Armouries Fecht1, the oldest surviving instruction book on sword fighting in Europe, which is still being used to learn this art today.

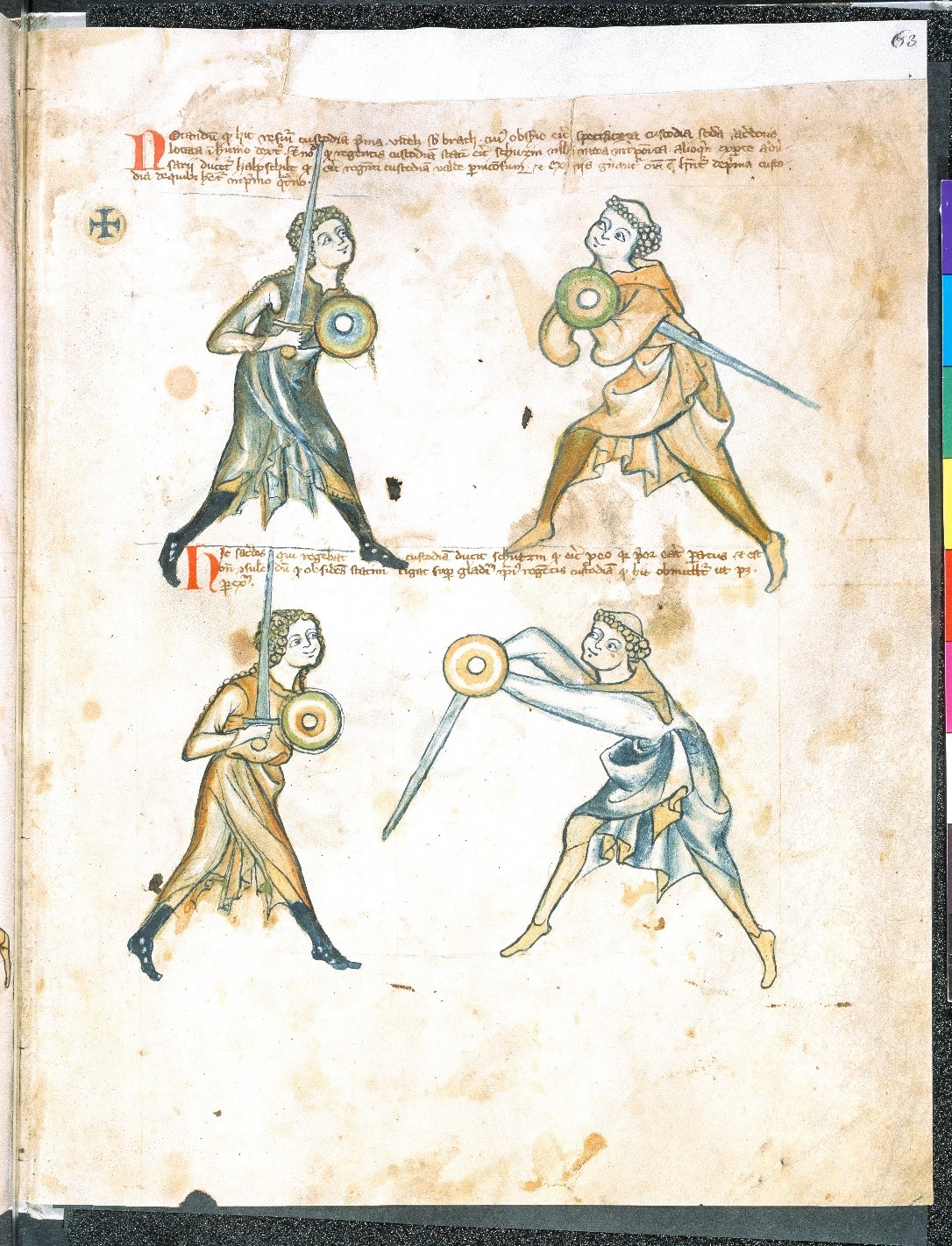

The manuscript, which has been dated to c. 1330 and is currently kept at the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds, England, consists of 32 leaves of vellum containing colour illustrations of fighters. Contrary to common thinking, no knights in armour are depicted, but a priest and novice are shown engaging in combat. The last two pages also show a woman in the novice’s role who is the priest’s opponent. The text itself is largely written in Latin with the exception of a few technical terms, which are in German. The book is concerned with techniques for using a sword and buckler (a small, round shield) together .

One of the scholars who has benefited from the knowledge recorded in this manuscript is Cornelius Berthold, a specialist in Arabic manuscripts and miniature Korans who has learnt how to fight in this historical manner and now teaches the subject as an instructor. Studying the Tower Fight Book, as MS Fecht1 is also known (since it was kept at the Tower of London for a while), not only taught him how to stand and hold the weapons in particular situations, but he also learnt a number of things about the manuscript itself from imitating and performing the techniques described and depicted in it.

The illustrations were painted before the text was written, which is rather unusual for medieval manuscripts, Berthold says. Judging from the style in which they were written, the explanatory descriptions were probably added one or two decades later in Thuringia, Franconia or Bohemia. The order in which the texts and illustrations were added can be deduced from how these elements overlap on the parchment. What is more, the commentaries are of varying lengths, but the space provided for them between the illustrations is always the same size. In fact, some of these texts are quite long and even run into the margin. Many of the commentaries in which the reader is directly addressed refer to the pictures, so the scribe must have had these in front of him at the time. In fact, he occasionally complained about illustrations that were missing, as we can see here:

nota quod non est plus depictum de illo frusco quam ille due ymagines quod fuit vicium pictoris

(‘note that only these two pictures of the [fighting] technique have been drawn, which was a mistake on the artist’s part’).

Fecht1 is the first historical book on swordsmanship that Berthold has studied in detail. It was not easy to get into the subject initially – if you take a closer look at the pictures and descriptions, you will quickly realise this work was not aimed at beginners; no detailed instructions are provided about the various techniques, nor are there any examples of basic exercises to help students practise them. In fact, the work seems to be a scholarly analysis of the art of sword fighting. It shows recurring situations in combat and lists the options that the two opponents have in them, illustrated by the initial and final positions adopted in the various fighting techniques. Presumably, the manual was intended for combatants with experience of practical training who were also expected to study the theory of armed combat with a sword and buckler. It repeatedly tells its readers to look at the combat situations closely, compare them with what they have already learnt and ask themselves which technique would be best in the current situation.

The only way to develop effective combat skills using the instructions in this manual today is by experimenting, comparing it with later sword-fighting manuals that are more detailed, and by learning from practice. Replicas of historical swords can be used, which are made as authentic as possible, but are usually blunt.

A number of folios in the fight book have been lost over the course of time. Various situations are depicted in the manuscript in which a hesitant opponent is supposed to be attacked with a thrust, for example, but this attack is not mentioned in one of the most frequent situations of engaging with an opponent, although you would normally expect to find it in the fighting system. Many inexperienced learners of the art are likely to have been puzzled by the omission at this point. In 2012, researchers analysed the quires in the book and discovered that several folios were missing. One of these gaps occurs at the very point where one would expect to find a description of the thrust. If nothing else, we have an indication that the technique did actually exist.

Fecht1 is not the only manual to have been written on sword fighting, but it is the oldest surviving one and is still consulted today by those interested in reviving this historical form of combat. It was read and admired for centuries. The aristocrat Heinrich von Gunterrodt from Saxony referred to the fight book in the sixteenth century (although it seems he was hardly able to read its writing) and at roughly the same time, Jörg Breu the Younger painted pairs of sword fighters for a manuscript on swordsmanship in Augsburg. The postures and clothing of the swordsmen show a striking similarity to what we find in Fecht1. Up until the Second World War, Fecht1 was kept at the Ducal Library in Gotha (also known as the Court Library, or Hofbibliothek). It then disappeared for a number of years under unexplained circumstances, only to reappear suddenly in 1950 when it was auctioned at Sotheby’s in London, which is how the Royal Armouries acquired it.

The manual is still raising questions to this day. Many of these concern its origins and how it was handed down over the years, but a number of them also relate to the content and the sword-fighting techniques depicted. The nice thing about this is that questions from scientists and interested lay people are equally well represented.

Anyone who would like to know what the art of medieval swordsmanship was like, which is so lavishly illustrated in the Tower Fight Book, can look up the old accession number of Fecht1 on the web: MS I.33 – it’s easy to find on YouTube...