PhD Research SeriesLost and FoundPiecing together Ottoman Libraries in European Borderlands

28 July 2025

Once a vital hub of Ottoman culture, Süleyman Efendi’s library was dispersed across Europe as a result of conquest. PhD researcher Rawda El-Hajji shows how tracing these scattered manuscripts helps reconstruct lost intellectual communities and reveals the fate of cultural heritage in times of conflict.

By Rawda El-Hajji

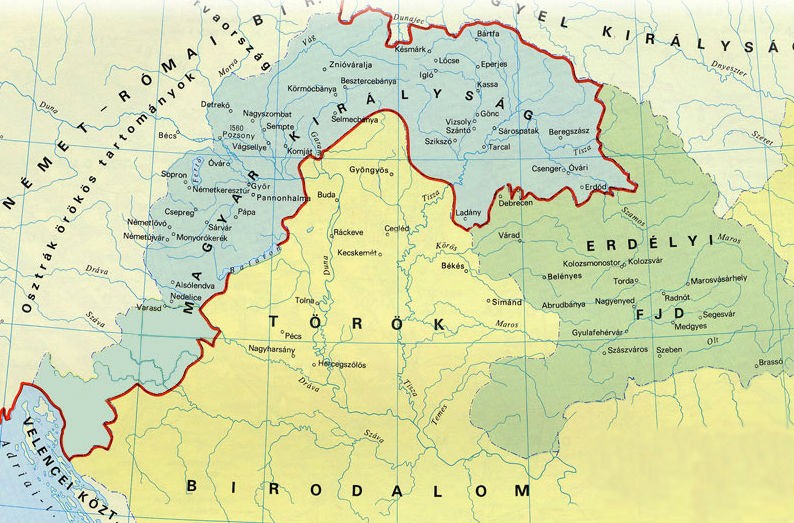

Books not only carry knowledge and texts, they also reflect the history and culture of the period in which they were produced through the voices and stories of those who owned them – whether as collectors, scholars or students. Old books are part of humanity’s cultural heritage that act as windows into histories that might otherwise be lost, in our case, to war and conflict. I am working in my research with manuscripts that were looted and displaced during the siege and battle of Vienna in 1683. Some of them once belonged to a library owned by a little-known preacher named Süleyman Efendi in seventeenth-century Buda (modern-day Budapest), then part of the Ottoman Empire (Fig. 1).

When European armies conquered Ottoman territories, they often appropriated valuable cultural items as war prizes, known as Türkenbeute in German. Some of these trophies, mainly manuscripts, found their way to German cities, where they helped spark Germany’s growing interest in ‘Oriental’ studies. While this dispersal disrupted the previous function of these works in their Ottoman-Muslim context, it inadvertently preserved pieces of Ottoman Hungary’s cultural heritage that might otherwise have been lost forever.

Süleyman Efendi and His Collection

Süleyman Efendi built a library that offers unique insights into Ottoman cultural life in the Empire’s European territories. As he carefully collected his books, he could not have known that his library would eventually be scattered across Europe – not by accident, but as a direct result of war and conquest. After almost a year of research and tracking down these manuscripts, I have been able to identify fifty-eight manuscripts scattered throughout Europe, with the greatest numbers being in Bologna, Italy, and Leipzig, Germany.

The main goal of the research is to track the different trajectories of these manuscripts and how they came into Süleyman Efendi’s possession in Buda before some were looted and others were likely destroyed. The collection was part of the broader network of Ottoman libraries stretching across South-East Europe, North Africa and West Asia. Ottoman libraries were more than just places to store books – they were vital centres of learning and discussion that existed alongside mosques and madrasas to preserve and share knowledge. This tradition was so important that Ottoman sultans regularly established libraries as part of their educational complexes, often near their tomb mosques. Some sultans chose to expand existing libraries rather than build new ones.

Süleyman Efendi’s collection holds special significance for now as our only surviving glimpse into the intellectual life of Ottoman Buda. Beyond the loss of intellectual and cultural context in these war zones, we also lose information about previous owners. How do we identify the ‘last’ owner of these manuscripts? We know this in the case of our collection from what is called an endowment deed. These deeds serve as detailed snapshots of cultural life from centuries ago. When someone donated books to a mosque or school library, these documents recorded not only the titles but often included information about who could use them, how they should be preserved and even where they should be stored.

In Süleyman Efendi’s case, he mentions only his first name, occupation and workplace. The mosque where he worked was originally the Church of Our Lady of Buda Castle (Fig. 2). When the Ottomans took control of the town in 1541, they converted it into a mosque and named it after Sultan Süleyman. This church held particular significance among Ottoman historiographers, as its conversion into a mosque marked the town’s conquest.

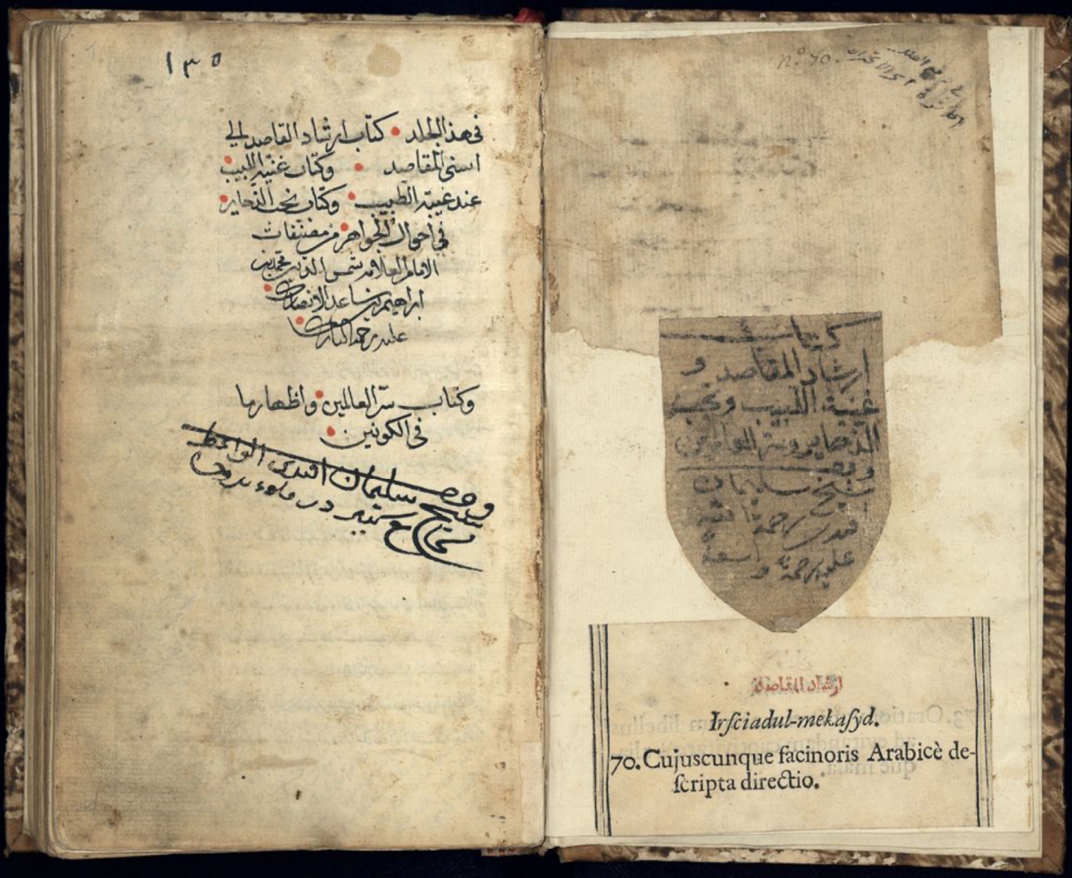

The central question remains: How do we piece together these scattered library collections and trace their history before they reached Europe? The process can be compared to solving a mystery with three different types of clues. Firstly, we study historical records that describe how Ottoman libraries functioned within their educational complexes, providing the framework for understanding these knowledge centres. Secondly, we analyse Süleyman Efendi’s collection alongside other surviving manuscript collections, revealing patterns of intellectual life across Ottoman Hungary. Thirdly, we examine the physical books themselves – their paper, binding, and especially the notes left by readers and owners (Fig. 3) – to understand how these texts were used within their communities. The books themselves tell rich stories through readers’ notes in their margins (known as marginalia).

These notes, written in both Arabic and Ottoman Turkish, reveal how readers engaged with the texts. In one manuscript, we find scholarly commentaries on interpretations of religious law, while in another, we discover medical recipes and records of births and deaths that document events during plague periods. These personal traces provide glimpses into the daily intellectual life of that region.

As a researcher at both the CSMC and the Bibliotheca Arabica project in Leipzig, I have access to an extensive database developed by Bibliotheca Arabica containing approximately 92,000 manuscript notes – most of them collected by Dr Boris Liebrenz. Many of the manuscript notes are already online. Through these notes, I can trace how manuscripts circulated, how they were used and how they were studied. Combined with research on other libraries, we can create a network similar to a ‘chat history’ or ‘browsing history’, revealing the educational legacy these communities shared and preserved. Moreover, similar libraries existed throughout Ottoman-controlled territories in Southeast Europe. By comparing Süleyman Efendi’s collection with surviving manuscripts from Belgrade and Sarajevo, we can map the broader pattern of intellectual life within and beyond Ottoman Hungary. This work across centuries helps us reconstruct how people shared knowledge in a multicultural empire.

I am embarking on a journey to track the different lives these manuscripts had before their displacement to Europe, bringing a lost institution back to life after centuries of fragmentation. Though Süleyman Efendi’s library now lies scattered across Europe, it continues to tell an important story – one that reveals how knowledge was preserved and shared across political and cultural boundaries in the European borderlands of the Ottoman Empire.

PhD Research Series

In this series of articles, PhD researchers from the CSMC Graduate School share insights into the themes of their work. All episodes will be published in Logbook, the CSMC blog. This is the fourth part of the series. An overview of all episodes published so far is available here.