No 47

Colourful Loyalty

An Embroidered Manuscript as an Object of Art and a Gift to the King of Bangkok

Around the turn of the twentieth century, a spectacular manuscript was created by a local princess in northern Thailand, who wanted to present it to King Chulalongkorn (r. 1868–1910) as a gift. The leporello manuscript was not written in a conventional way with ink on mulberry paper, but the letters were embroidered in varicoloured silk on black cloth. Princess Bualai, who created and donated this unique piece of work, was well known for her embroidery skills, as she frequently presented embroidered objects such as curtains, pillows and triangular backrests to the King in Bangkok, who kept them in a special chamber of the royal palace named the Bualai Chamber in honour of the princess. This embroidered manuscript is a unique case in Thai manuscript culture due to its artistic quality when compared to other works of Thai calligraphy. What exactly was the princess’s reason for making such a precious gift in the form of a manuscript?

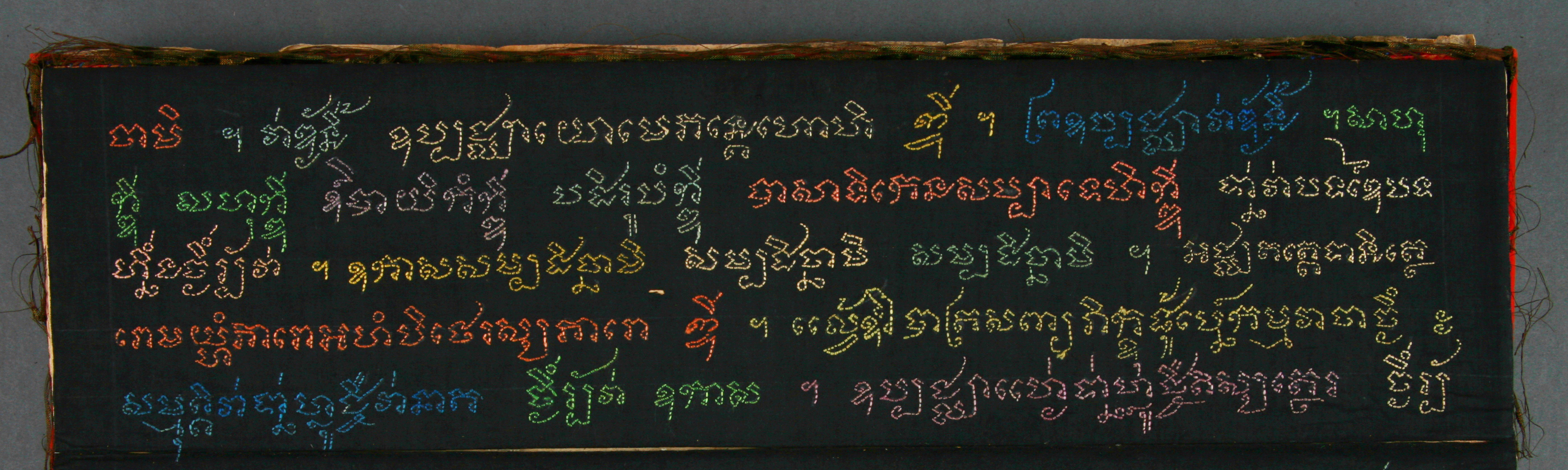

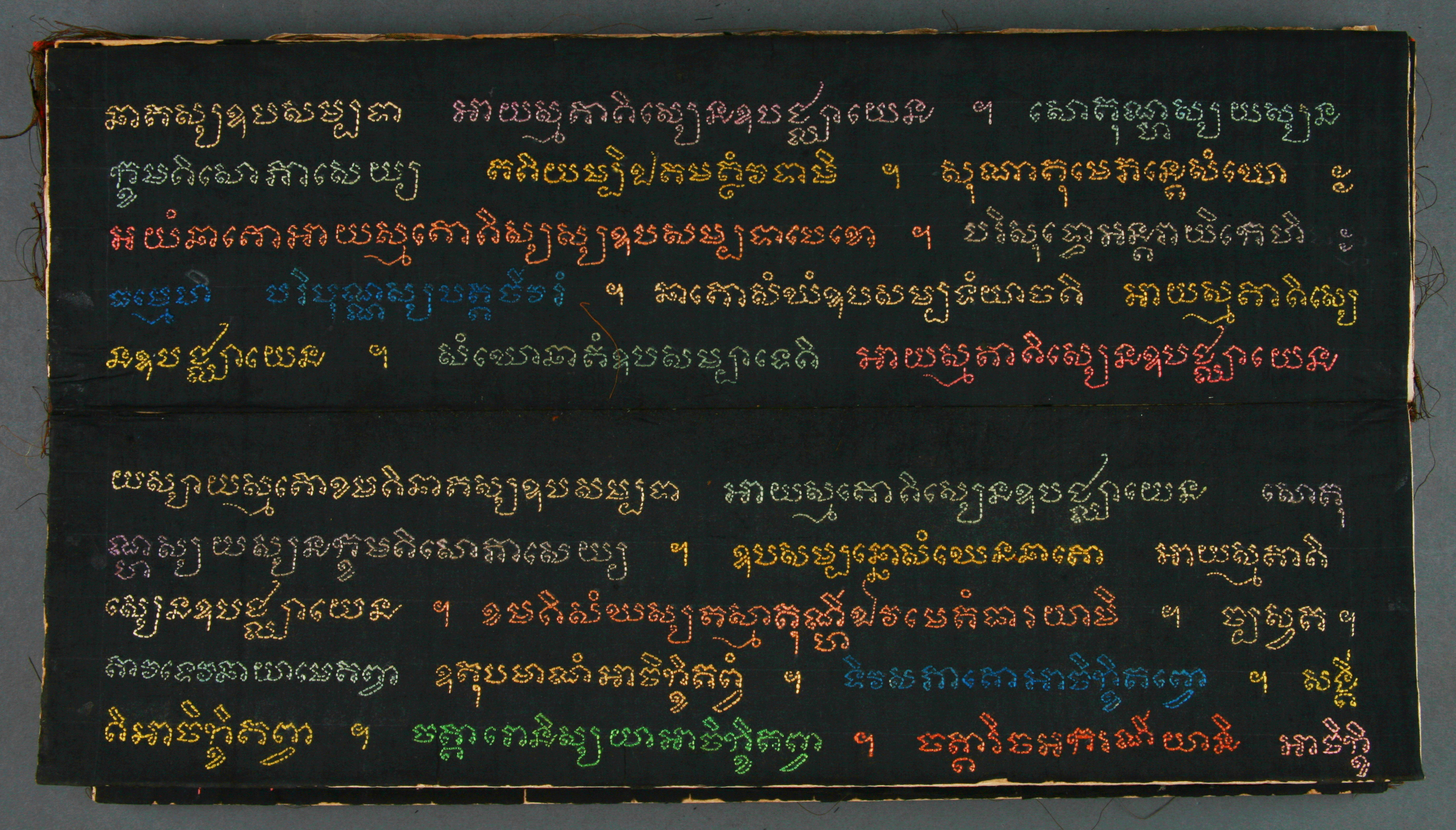

At present, the manuscript, comprising 24 folded pages and a colophon, is kept at the National Library of Thailand, where it is known as MS no. 134 (see the extracts shown in figs. 1 and 2). The front and back covers are both made of wood wrapped in black cloth. Flowers embroidered with golden and silvery silk thread are decorated on the cloth on the covers (fig. 4). The writing is embroidered in silk on a long, blackened cloth, which is firmly attached to a long panel of thick paper. The panels of paper covered in black cloth are stacked on top of one another just like a leporello manuscript. The colour of the embroidered letters changes every sentence or every quarter stanza (figs. 1–2). The script used for the manuscript is the type called ‘neat’ by Thai scholars – the Khòm script, a variety of Old Khmer lettering normally used for religious texts within the manuscript culture of central and southern Thailand, but not in old Lan Na, the northern region of present-day Thailand, where the tradition of the Dhamma script flourished most impressively.

The text is entitled Yatticatutthakammavācā Uppasombot, derived from Pali (the sacred language of Theravadin Buddhism in Sri Lanka and the South-east Asian mainland) and meaning ‘request for ordination’.

Kammavācā is a generic term for different kinds of texts used for monastic rituals and ecclesiastic acts. The text of this manuscript is a type of kammavācā used for the ordination of monks. The main text is a collection of Pali verses originating from the Vinaya Pitaka (monastic rules), but these are also accompanied by ceremonial instructions and explanations written in vernacular Thai. This manuscript does not appear to have been used in any monastic ceremony, however.

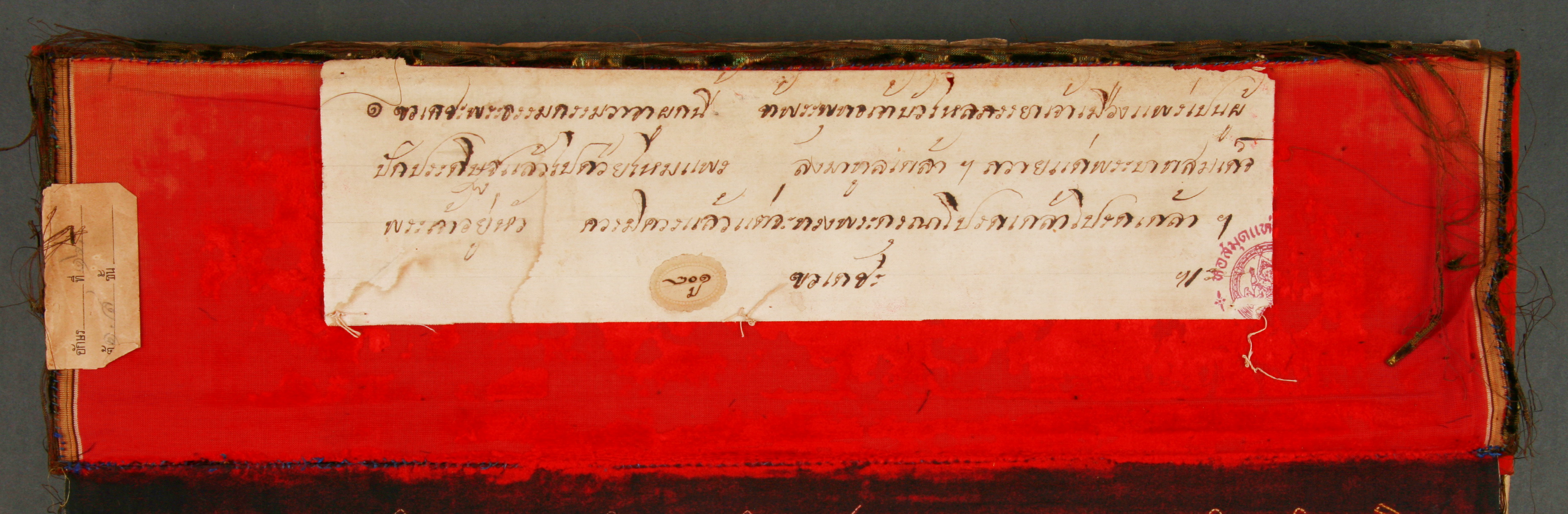

The colophon (fig. 3) was written on an additional label in Thai with (Central) Thai secular script:

“May it please Your Majesty: I, Princess Bualai, the consort of the governor of Phrae, embroidered [this manuscript] completely with silk, sending it down [south] to present to Your Majesty. May the matter rest upon Your Majesty’s judgement.”

Although the exact date the manuscript was created is unknown, Princess Bualai still refers to herself in the colophon as the consort of the local prince of Phrae, so it is most likely to have been created during the period in which her spouse, Prince Phiriyathepphawong, held this position (i.e. 1889–1902).

The ornamental writing in what could be seen as a type of illuminated manuscript is a masterpiece of calligraphy. The artistic focus of the writing here is not on the embellished form of the handwriting, however, as the writing in the manuscript adheres fully to the standard ‘neat’ type of the Khòm script. Rather, its calligraphic focus is on the high quality of the silk embroidery and the variety of colours used. This manuscript, therefore, combines an artistic form of writing with the art of embroidery. In seemingly stark contrast to the apparent religious function of the text, the manuscript might have been kept in King Chulalongkorn’s collection in the Bualai Chamber, where its beauty could be admired frequently by the King. This indicates a shift of the manuscript’s primary function from that of a work intended for religious ceremonies to that of an object of art.

Furthermore, in view of the fact that the Siamese government of Bangkok had brought the local principalities in northern Thailand under its control in the late nineteenth century, the presentation of this object of art as a gift to the King of Bangkok can be interpreted as an explicit expression of the local princes’ loyalty and acceptance of Siamese suzerainty. The manuscript thus contains a political message as well, especially in view of the use of the Khòm and Thai scripts instead of the Northern Thai Dhamma script, which would have created exactly the opposite political message due to the ever-present conflicts in the region at that time.

As Princess Bualai’s manuscript is one of very few Thai manuscripts that were created with the special intention of being objects of art and it combines the skill of writing with the art of embroidery, it is a unique example of manuscript production from around the turn of the twentieth century. The significance of this manuscript lies in its codicological and cultural aspects, and not, as perhaps a first glance might suggest, in the words it contains.

References

- ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF NORTHERN THAI CULTURE สารานุกรมวัฒนธรรมไทย ภาคเหนือ. (1999): “Bualai Theppawong, Mae Cao บัวไหล เทพวงศ์, แม่เจ้า”. In: Foundation of Thai Cultural Encyclopaedia. Saranukrom Watthanatham Thai Phak Nüa Lem 7 สารานุกรมวัฒนธรรมไทย ภาคเหนือ เล่ม ๗. Bangkok: Foundation of Thai Cultural Encyclopaedia, Thai Commercial Bank, 3418–3420.

- GINSBERG, Henry. (1989): Thai Manuscript Painting. London: British Library.

- GRABOWSKY, Volker. (2011): “Manuscript Culture of the Tai”. In: Manuscript Cultures, 4, 145–156.

- HINÜBER, Oskar von. (2000): A Handbook of Pali Literature. New York: De Gruyter.

- IGUNMA, Jana. (2013): “Aksoon Khoom: Khmer Heritage in Thai and Lao Manuscript Cultures”. In: Tai Culture: Interdisciplinary Tai Studies Series, 13, 25–32.

- ONGSAKUL, Sarassawadee สุรัสวดี อ๋องสกุล. (2010): Prawattisat Lanna ประวัติศาสตร์ล้านนา. Bangkok: Amarin Publishing.

- PUNNOTHOK, Thawat ธวัช ปุณโณทก. (2006): Aksòn Thai Boran Laisü Thai Lae Wiwatthanakan Aksòn Khòng Chonchat Thai อักษรไทยโบราณ ลายสือไทยและวิวัฒนาการอักษรของชนชาติไทย. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University Press.

Description

The National Library of Thailand (Bangkok)

Shelf mark: MS no. 134 “Yatticatutthakammavācā Uppasombot”

The Illustrated Manuscript Subsection, The Secular Manual Section, The Manuscript Collection

Pali and Thai language, Khòm script

Material: cloth attached to a pile of thick paper, cloth embroidered with silk in the form of writing, 24 folded pages.

Dimensions: 45 x 13 x 3.8 cm

Provenance: c. 1900, Phrae Province, northern Thailand

Reference note

Peera Panarut, “Colourful Loyalty”

In: Andreas Janke (Ed.): Manuscript of the Month 2015.11, SFB 950: Hamburg,

http://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/mom/47-en.html

Text by Peera Panarut

© for all images: The National Library of Thailand (Bangkok)