Swimming Like a Samurai – A 110-year-old Japanese Scroll

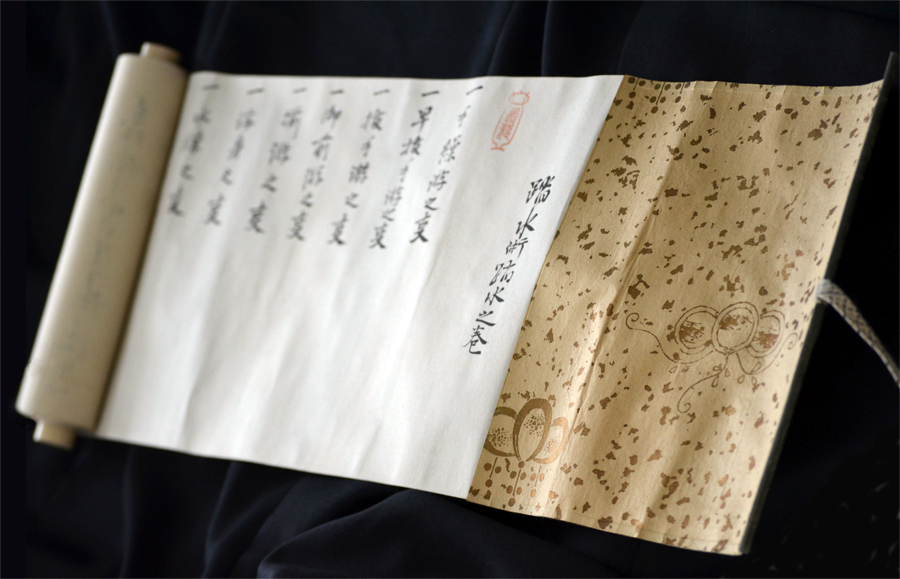

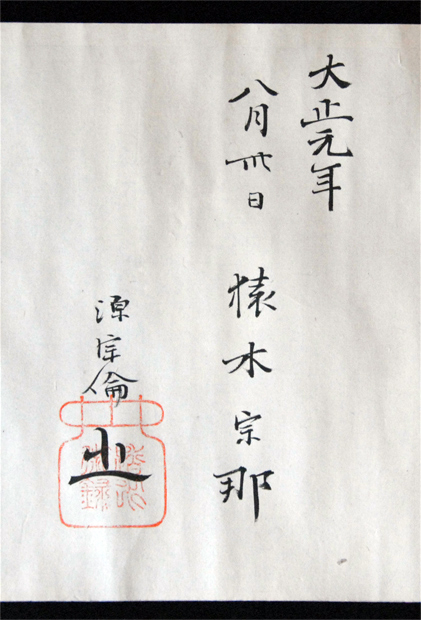

The 13 August 1912 was a special day for Maki Toshitsugu, student of the Kobori ryū tōsuijutsu 小堀流踏水術 tradition. On that day, his teacher, Saruki Muneyasu, signed the licence Tōsui no maki. The student received it as proof of his dedicated training in the art of suijutsu 水術. The scroll he received symbolizes the second of four skill levels that can be achieved in that tradition. With each new level, the student receives a new scroll, containing parts of the Kobori ryū’s secret knowledge which has been handed down from generation to generation.

The Kobori ryū focuses on a rare form of Japanese martial arts: classical combat swimming (jap.: suijutsu). The word ryū 流 translated can have the meaning school, tradition or style. Water as both an element of nature and an artificial barrier has always been a part of military relevance so the classical swimming styles of Japan also fit into the martial arts of the samurai. The training covers various swimming techniques such as the art of swimming in armour and fighting in the water.

K. Helmholz

Unlike Judo or Karate where the level of a student can be determined by the color of the belt, the classical martial arts use a system of licenses. With each new level the student is awarded a new license, a written document proving his progression. The licenses range from a simple certificate to a book or a scroll and are usually written by the head or the main teacher of a school. The more complex documents are often replications of those passed on within the tradition. They are the tangible heritage of a school. The Tōsui no maki is a perfect example of such a license both in structure and in content.

K. Helmholz

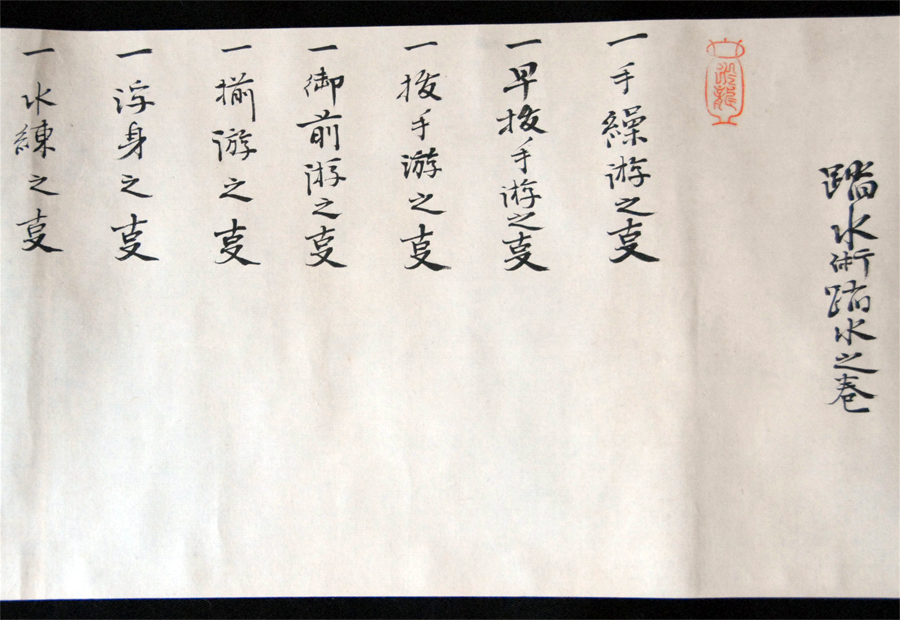

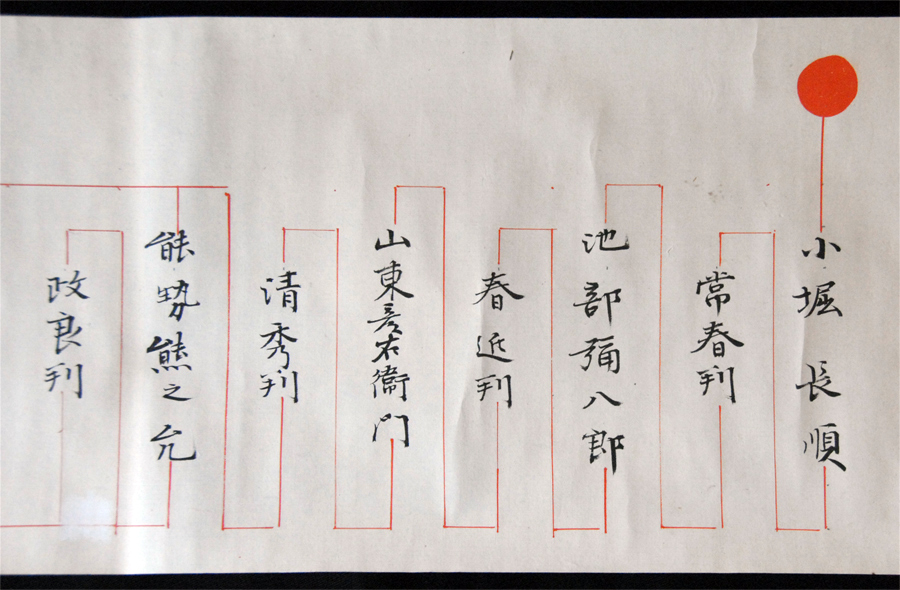

The text can be divided into five sections covering the three essential elements of the tradition: the swimming techniques, the philosophical foundation of the art and the history of the tradition. The text starts by naming basic techniques which are subsequently described in detail. The part on physical training is followed by two texts about philosophical issues such as the correct mental attitude during training. Following that is a genealogical chart that shows all heads of the school. The founder is marked with a rising sun symbolizing the beginning of the tradition. The last name in the chart is that of the scrolls scribe. The colophon at the end of the scroll bears the name and seal of the copyist and the name of the student who received it.

K. Helmholz

The relationship between the teacher and the student is a very crucial factor in the classical martial arts. That is why even today these important documents are being written by hand for each individual student, thus making each one unique. In the past, a school's techniques and other knowledge were well guarded military secrets. Although this is no longer the case today, the knowledge is still only meant to be shared with the students of a school. For that reason, the scroll is not translated or depicted in its entirety.

K. Helmholz

The copyist of the scroll, Saruki Muneyasu, was the sixth head of the Kobori ryū and acted as both guardian of the tradition and its most prominent teacher. Unfortunately for the student though, their connection was not going to last much longer. Less than two months after having finished the scroll, Saruki died at aged 64 on 5 October 1912. As it had for centuries, the task of safekeeping and sharing the tradition further fell to a new successor, Kobori Heishichi.

K. Helmholz

The scrolls fate after 1912 is unknown. It is very likely that it was kept for many years until the scrolls real and symbolic value were finally forgotten. 96 years after being written it was up for sale in an online auction for Japanese antiques. At the end of a very long night, the author of this article managed to buy the scroll, outbidding one other potential buyer in the last seconds. The next day he received a message and found out that the other bidder was a member of the Kobori ryū with whom he had been in touch with years earlier. The member had supplied the author with information on the history of the school that had supported him in his research at that time. As the new owner of the scroll the author promised, out of respect for the tradition, not to sell the scroll again but instead return it to the Kobori ryū at an appropriate occasion.

In recent years, the number of classical martial arts manuscripts being sold has increased. They are sought after by collectors all over the world and often render prices well beyond 10,000 dollars. Most schools do try to do their best to keep these important and valuable documents within their traditions ensuring their preservation for future generations.

References

- Imamura, Yoshio (1966), „Suijutsu 水術“, in: Nihon budō zenshū dai yon kan 日本武道全集第四巻, Tōkyō: Jinbutsu Ōraisha, 225-402.

- Mol, Serge (2001), Classical Fighting Arts of Japan. A Complete Guide to Koryū Jūjutsu, Tōkyō, New York, London: Kodansha International Ltd.

- Seo, Kenichi (1974), Nihon eihō ryūha shi no hanashi. Kobori ryū, Shinden ryū sonohoka 日本泳法流派史の話, Kyōtō.

- Watatani, Kyoshi (1978), Bugei ryūha daijiten 武芸流派大事典, Tōkyō.

- Yokose, Tomoyuki (2000): Nihon no kobudō 日本の古武道, Tōkyō.

Description

Private Collection

Material: Paper, 19,5 × 503 cm,

Format: Scroll, wooden roller with white end pieces, partial protective cloth cover

Provenance: Japan (presumably Kumamoto), 1912

Following to the japanese custom, the family name preceeds the given name.

Text by Karsten Helmholz

© für for all images: Karsten Helmholz, Hamburg

* Update: In August 2019 the scroll was returned to the current head of Kobori Ryu in Kumamoto.