Postcards from Laos

6 March 2023

The forests and villages around Luang Prabang belong to the few places in the world where the Lao tradition of making manuscripts is still alive. Agnieszka Helman-Ważny and Volker Grabowsky have set out to preserve the knowledge of a fading culture. Here they share some impressions of their journey.

Photo: Agnieszka Helman-Ważny

The former royal city of Luang Prabang lies at the confluence of the Mekong and the Nam Khan rivers in the mountainous northern region of Laos. With its rich Buddhist heritage and the perfect harmony of traditional architecture and urban modernity, the town was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1995. Since then, Luang Prabang has become one of the favourite destinations for international tourists.

Occasionally, though, you get the impression that the city’s commercial success makes it harder to see beyond its alluring charm and to get to know this unique place and region more deeply. Most visitors do not take sufficient time to really dive into Laotian culture and history unless they have a particular reason and interest to do so.

Photo: Agnieszka Helman-Ważny

Fortunately for us, we had such a reason. Together with Khamvone Boulyaphonh, Vongphasith Chanphakeo, Tia Homsengphan, and Thak Vannosin, we gave ourselves the task to document the still existing culture of producing manuscripts in Laos. This work is part of the research we do at CSMC (see the projects on ‘A Fading Tradition: The Production of Manuscripts in Northern Thailand and Laos’ and ‘History of paper of ethnic groups in Southwest China and mainland Southeast Asia’).

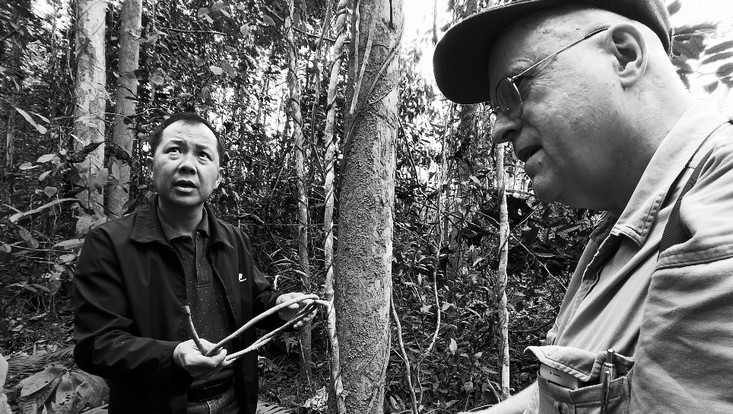

Over the last two weeks, we have been interviewing experts who are still active in the manuscript-making tradition in Luang Prabang Province. We came across a number of practicing scribes, sites of papermaking, and people who were willing to share their knowledge with us. These encounters are an invaluable opportunity to better understand the resources, skills, technologies, and social values involved in the process of making manuscripts in Laos. For instance, thanks to the information we received from the locals, we discovered and documented the existence of a rare plant used for making a special kind of paper with an exceptionally smooth surface.

Photo: Agnieszka Helman-Ważny

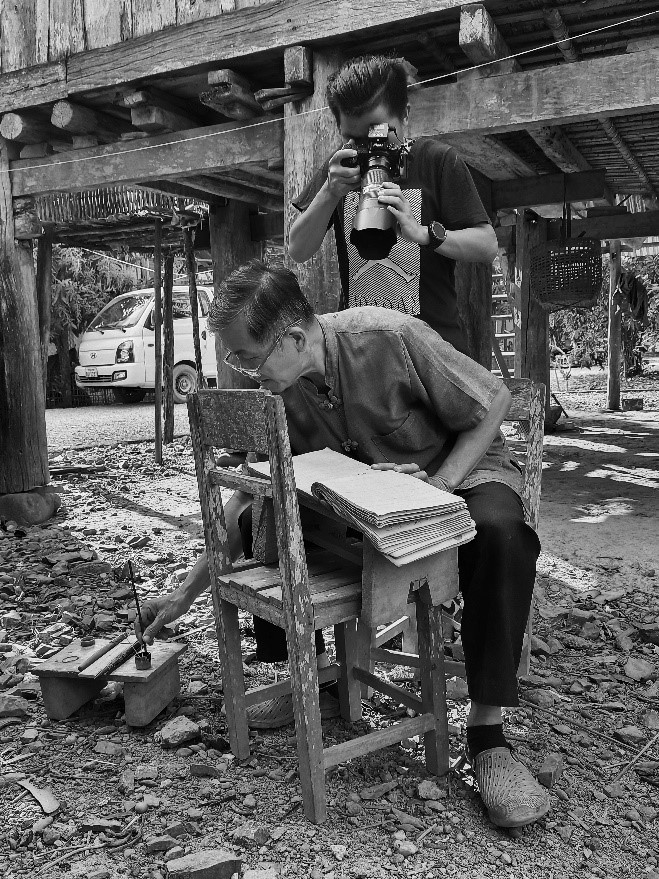

There has not been a systematic study of the material dimension of manuscript production in Laos so far. Since the number of people with scribal expertise is constantly dwindling, we must document any instances of local craftsmanship promptly. Each journey might be the last chance to witness some of the traditional ways of making manuscripts in Laos, such as the production of ink and paper, cutting pens, and the inscription of text on palm leaves and mulberry paper.

One of the individuals from whom we learned about traditional methods of making paper in Laos is Miss Noyna, the owner of the Porsaa (Pòsa) papermaking factory. In 1995, her father, who learned the papermaking crafts in Chiang Mai and the Nan provinces in Northern Thailand, established the Sainamkhan Company, which is located in the Müang Nga village in Luang Prabang town. According to him, the old techniques were brought to both Thailand and Laos from mountain people (possibly Hmong among others), but there is no certainty about this.

Photo: Agnieszka Helman-Ważny

Miss Noyna and her family members were the first to gather plants used for papermaking. In the forests north of Luang Prabang town, they collected the bast of sa plants (paper mulberry) and sold it to Thailand. Eventually, they decided to produce paper themselves, which required gathering skills and knowledge about the technology used for making paper. Although they have slightly adjusted their methods to economic requirements, their factory, which is unique in Laos today, is an excellent place to learn about the transfer of knowledge, the production process, and materials and tools available in the vicinity.

The history of books in Laos is scarcely known in the West. Nevertheless, Lao book culture is part of the rich manuscript-making tradition of the upper part of the South-East Asian mainland, which culturally and historically included large parts of southwestern Yunnan. This is the home of Tai speaking ethnic groups, such as the Tai Lü and Tai Nüa, who are closely related to the Lao. It is predominantly these two groups, some of whose members have also settled in northern Laos, who use various kinds of sa paper as writing support. In contrast, the Lao prefer to write on palm leaves. Indeed, there are still thousands of hidden palm-leaf and paper manuscripts that are being preserved in various monasteries and private homes.

Photo: Agnieszka Helman-Ważny

In recent years, the appreciation for old manuscripts and material objects has grown. This has stimualted preservation projects and studies of materials used in the process of making books. Although books can be a valuable source of information about historical craftsmanship, not all aspects about the technology and social context of production processes can be retrieved through material and codicological analyses. This is why it is so important to document both the preserved old manuscripts and the tradition of making manuscripts, which is still alive today but fading. Laos is one of very few places in the world where we can still witness this tradition. If we know what materials, techniques, and technologies were used, we are in a much better position to interpret the outcomes of material analyses of manuscripts that are preserved in libraries and museums around the world.

About the Authors

is the Principal Investigator of 'History of Paper of Ethnic Groups in Southwest China and Mainland Southeast Asia (in Zomia)' at the Cluster of Excellence UWA. She will also be the spokesperson of the new Working Group on 'Asian Highland Manuscripts: Manuscript-Making beyond the State', which will be launched at the upcoming workshop on 'The Body of the Spoken Word: The Interconnection of Ritual, Text and Manuscript in Bon and Naxi Traditions' (24-25 March 2023).

is Principal Investigator of 'Traditional Knowledge in Cultural and Material Transformation: Inscriptions of Wat Pho Monastery (1831–1832) and Thai Manuscript Culture' and 'Anisong (Ānisaṃsa) Manuscripts from Luang Prabang (Laos) in a Comparative Perspective: Transformation in the Age of Printing' at the Cluster of Excellence UWA. He is also the Co-Principal Investigator of DREAMSEA.