PhD Research SeriesBeyond PrintUnlocking Multilingual Secrets in Tamil Classical Manuscripts

14 July 2025

Early Tamil poetry, rich with tales about journeys, patrons, and cultural exchange, reveals a vibrant blending of languages. PhD researcher Maanasa Visweswaran explores how Sanskrit influences and the use of Grantha script shaped these classical Tamil manuscripts.

By Maanasa Visweswaran

Black silt, once graced by jasmine blooms scattered by koel birds along the banks of the forest river during spring, became like scorching lances once summer hit. It was upon this black silt that a bard accompanied by his huge clan made their way, with musical intruments in their hands, but nothing in their bellies. Hunger propelled them onwards despite their painful journey through the parched landscape. In the midst of desolation, an experienced bard meets this poor bard and his clan and addresses him: ‘Oh supplicant of ancient truth who longs for benefactors in this world!’. He then counsels them to embark on a journey towards the liberal Nalliyakkōṭaṉ, revered king of the hilly terrain (kuṟiñcikkōmāṉ), and gives them a vivid itinerary on the landscapes they must traverse – coastal vistas, lush forests and fertile fields. The experienced bard beckons them to journey forth to Nalliyakkōṭaṉ, who would outshine all others in his generosity, furnishing them with wealth, an abundance of food and a chariot complete with a charioteer.

This is the central theme of an old Tamil poem known as the Ciṟupāṇāṟṟuppaṭai, which belongs to a poetic genre called Āṟṟuppaṭai, meaning ‘setting on the path’. In this genre, an experienced bard, poet or dancer guides another towards a benevolent patron, from whom they might receive the same wealth necessary to escape the clutches of dire poverty. These songs typically serve as a cartographic guide, illuminating the landscapes that the supplicants must traverse – capturing both the beauty and the inherent dangers of their journey. The experienced performer in another Āṟṟuppaṭai composition known as the Malaipaṭukaṭāam advises another performer to use the poles of his drum as walking sticks, so that he may avoid slipping and falling on the treacherous mountain path.

These songs are part of a body of work known as the Caṅkam corpus, which comprises some of the earliest Tamil literature. To begin with, you may wonder: What is Tamil? What is the Caṅkam corpus?

Tamil is a Dravidian language originating in the southern tip of India. Tamil has served for the past two millennia not only as a spoken language but also as a refined literary medium. By contrast, Sanskrit, originating from the north and belonging to the Indo-European family of languages, has functioned as a unifying lingua franca across diverse regions of India. Scholars refer to the widespread use of Sanskrit as a language of prestige during the first millennium CE as the ‘Sanskrit cosmopolis’ – a vibrant cultural and intellectual network that spanned various parts of Asia. Thus, Tamil and Sanskrit, despite belonging to different language families, interacted for around two millennia, and these interactions only increased with time.

Returning to our poem, there are already traces of some Sanskrit influence that reveal themselves in the Ciṟupāṇāṟṟuppaṭai. The food Nalliyakkōṭaṉ provides, for instance, is prepared according to a cooking manual authored by Bhīma, a character from the Sanskrit epic Mahābhārata. The poem does not state this explicitly; instead, it describes all of this by means of riddle – that this cookbook was written by the elder brother of the one who set a forest ablaze with his arrows. Only the reader (or listener) familiar with Sanskrit mythology would know that these refer to the characters Bhīma and Arjuna, respectively. They would make the connection that in the Mahābhārata, Bhīma disguises himself as an exceptional cook called Vallabha in the kingdom of Virāta during the year of his undercover exile, and that, on another occasion, Arjuna burns the Khāṇḍava forest to construct the capital city of Indraprastha (but that is a tale for another time).

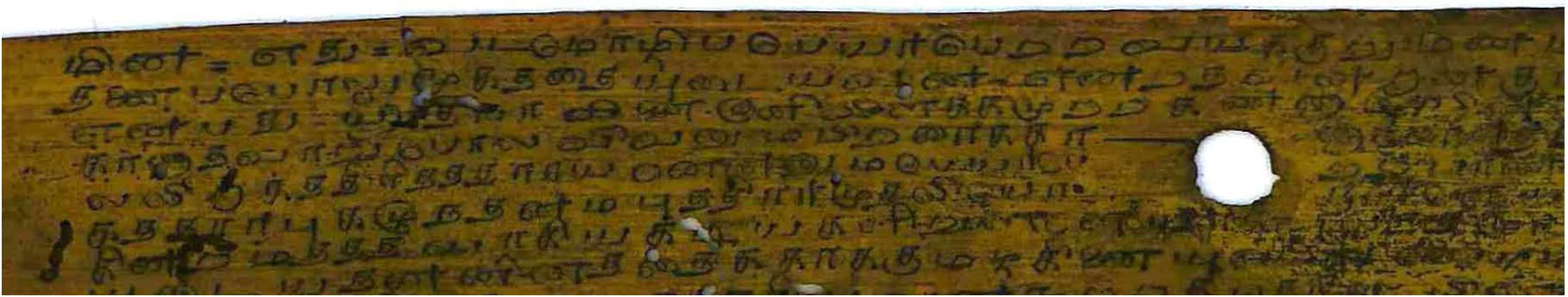

What, then, is the Caṅkam corpus? This collection represents the earliest body of Tamil literature, originating as a fluid compilation of oral poems centred on themes of love and war. Over time, during the mid-first millennium CE, these poems were transformed into written lyrical anthologies, probably inscribed on palm-leaf manuscripts. These songs would have been copied numerous times. They were supplemented with commentaries at some point during the first half of the second millennium. Regrettably, due to the hot and humid conditions of South India, the earliest extant Caṅkam manuscript can only be dated to the late seventeenth century.

While signs of multilingual interaction already appear in poems from the early first millennium CE, the influence of Sanskrit increased over time. By the end of that millennium, nearly half of the entries in Tamil lexicographical texts contain Sanskrit words. This linguistic blending in the manuscripts of Caṅkam poems is particularly observable in their commentaries, where Tamil terms were sometimes explained using Sanskrit written in Grantha script. However, with the advent of printing technology and significant political changes, traces of Grantha were gradually eliminated.

Our project on ‘The Use of Grantha Script in Classical Tamil Manuscripts’ (RFH03) tries precisely to uncover this mixed script tradition, particularly within the context of the Caṅkam corpus, which is seen as predating any Sanskrit influence. Recent studies have revealed that Grantha is indeed present in some Caṅkam manuscripts. Thus, we chose the Ciṟupāṇāṟṟuppaṭai for this project since it is part of a slightly later layer of the Caṅkam corpus, accompanied by a commentary from a time when multilingual interactions flourished in the second millennium CE. We are looking to explore if Sanskrit loanwords are indeed used to explain Tamil terms in the Ciṟupāṇāṟṟuppaṭai and whether we can find Grantha in our manuscripts.

This poem has been preserved in ten manuscripts – eight palm-leaf and two paper manuscripts. Our goal is not just to translate the poem; we also want to explore Sanskrit influences on the manuscripts themselves. We are asking questions such as: Why do some manuscripts include Grantha while others do not? Were these choices deliberate? Were the manuscripts created in multilingual settings?

It is easy to assume in our modern world, where texts are often printed and seen as fixed entities, that they have always existed in such a static form. However, revisiting these manuscripts reveals a wealth of information about their transmission histories and the contexts from which they emerged. Just how vibrant was the Tamil scholarly scene at that time, and to what extent was it multilingual? Was there a deliberate choice to promote or avoid multilingualism? Did religious affiliations influence these decisions? By studying multilingualism in these texts, we are led to think about where these manuscripts come from and explore the broader question of not just how something is multilingual, but why it is so.

PhD Research Series

In this series of articles, PhD researchers from the CSMC Graduate School share insights into the themes of their work. All episodes will be published in Logbook, the CSMC blog. This is the third part of the series. An overview of all episodes published so far is available here.