5 Questions to...Martin Jörg Schäfer

16 February 2023

In ‘5 Questions to…’, members of CSMC chat about their background, what motivates them, and their favourite written artefacts. In the case of Martin Jörg Schäfer, the latter was part of no less than the most prominent theatre scandal in the German-speaking world.

Martin Jörg Schäfer, please tell us a little about yourself.

I grew up Schleswig-Holstein and was interested in European (mainly German and English) literature, theatre, and philosophy without really believing that one could make a living from that fascination. I started studying literature at Universität Hamburg and later at University College London. At the same time, I was bouncing around between student and independent theatre projects and different jobs at Hamburger Kammerspiele, a more established playhouse. (There, I once worked as stage manager for a production that earned the distinction of being declared ‘most annoying theatre experience of the year’ by a leading local critic.)

It was only when I was offered an assistant director position that I realised that I much preferred to pursue my studies. I never lost sight of the performing arts but at first focused on the relationship between literature and philosophy (with a doctoral thesis on Paul Celan’s reading of Heidegger, who had been entangled with National Socialism, when writing his poetry in view of the Shoa). While writing my thesis, I held my first academic position within the German Research Foundation Priority Programme on ‘theatricality’, where I wrote a study on theatre metaphors and concepts in German idealism.

Since then, I’ve held various positions inside and outside of Germany and learned to appreciate academic contexts that are transnational as well as inter- and transdisciplinary. It makes one broaden one’s own horizon. Sometimes things may become demanding and slow, but one is constantly challenged in one’s own wheelhouse; and that’s a good thing.

In 2014, my work on perceived cultural crises and transformations of traditions led me back to Universität Hamburg. It is wonderful to be back at my alma mater and only sometimes a little bit too close to home. My work here is very fulfilling: among other things, I work on contemporary theatre and performance and spend whole seminars exploring the Hamburg scene together with the students.

However, my position is also ‘on the fence’ in some respects: literature studies approach the performing arts via the literary text; theatre studies often ignore the textual dimension so as not to be subsumed as a side show to the literature departments. This is where my interest in written artefacts has emerged from in the last years: by either looking at the text or the performance, literature and theatre studies largely ignore the written artefacts that form the infrastructure for both: prompt books, director’s logs, prop lists, et cetera. These written artefacts used to be manuscripts, but even in the ever more digitised work processes of today handwriting is still everywhere: as lists, personal notebooks, revisions on printout, et cetera. I find it fascinating to explore the materiality of these written artefacts in its own right and not just as a stepping-stone to analyse the dramatic text or the performance.

Handwriting persists at every turn. It is the mode of enrichment to update printed, typed, or copied written artefacts.

What are you currently working on?

Together with Alexander Weinstock, I’m working on a monograph on ‘Handwritten Theatre’ (hopefully to be published in early 2024). Our book will focus on late 18th and early 19th century prompt books from the Hamburg collection at Staatsbibliothek but will have a broader methodological and theoretical focus. The rise of modern European theatre since the 16th century depends on the proverbial emergence and predominance of letterpress printing; at the same time, a distinct, internally diverse, and heavily under-researched manuscript culture emerges within European theatre, with prompt books as the most prominent written artefacts, which ensure the (technical and textual) repeatability of the respective production (sometimes for decades).

Our study combines perspectives, methods, and questions from the fields of manuscriptology, theatre studies, and literary studies to an interdisciplinary approach towards written artefacts in modern European theatre. In the study of the performing arts, written artefacts have been primarily viewed as conveyors of information, that is, auxiliaries to gain knowledge about past live performances or to reconstruct the stage adaptation of the text. In contrast, our study conceptualises the entanglement of the changing materiality of the written artefacts, their use in performance, and their (changing) relationship to the respective performance history as well as to the versions of the literary text circulating in print. The upkeep and regular updating of the written artefacts (according to various requirements and demands, both intra- and extra-theatrical) lead to their constant enrichment with interacting layers produced through different writing tools by multiple hands and with various paper techniques. These processes have resulted in a unique material biography for each written artefact.

Your current research project at CSMC draws on theatre prompt books from Hamburg, covering more than 100 years from the 1870s to the 1980s. How did you get interested in this particular type of written artefact – and which play do you wish you had been present at based on the annotations in the prompt book?

Staatsbibliothek Hamburg has a large collection of written artefacts on local performing arts. After researching the prompt books from the time around 1800 and establishing a new approach, it seemed like the logical continuation to turn to more recent examples. While the earlier prompt books originated from the ‘Stadt-Theater’, which later focused on musical performances and became a precursor to today’s opera, the more recent ones have emerged from the playhouses that are still prominent today: Schauspielhaus, Thalia Theater, Kammerspiele. Anna Sophie Felser and I are especially interested in shifts and consistencies of manuscript practices as well as in the interaction with new or updated technologies. The use of printed books as a material basis becomes more common; typescripts and carbon copies come in as well. Yet, handwriting persists at every turn: manuscripts coexist with prints and typescripts; handwriting is the mode of enrichment to update printed, typed, or copied written artefacts.

The early 20th century is also the time in which artistic directors, instead of just arranging the performance according to the text, begin to imprint their ‘aesthetic vision’ on the production. Often, they turn interleafed prints into hybrids between personal notebook and production manual, containing sketches of the stage design, comments on the technical procedures, the director’s specific interpretation of the text, and other remarks of any kind. Particularly promising are instances in which we have the director’s log, the stage manager’s prompt book, and personal textbooks for an actor or two. Anna Sophie’s doctoral thesis will focus on director’s logs by Leopold Jessner, who rose to fame in Berlin in the 1920s but cut his teeth at Thalia Theater Hamburg which, before his arrival, had been more of a place for comedy and amusement. Since most of his estate got lost in exile after 1933, the Hamburg written artefacts are of great significance.

While it is difficult to re-imagine a historic performance based on a prompt book or a director’s log, it is fascinating to see how the respective written artefact takes on a life of its own. I would have loved to be present for Jessner’s production of Georg Büchner’s Danton’s Death in 1910, for which we have the stage manager’s prompt book. Today, this 1835 play on the reign of terror during the French Revolution is considered a ‘classic’. However, until the early 20th century, it was deemed ‘unplayable’ because of the numerous and quick scene changes. Jessner was one of the first to stage it. He largely did without any scene changes but relied on an abstract stage with alternating blue, red, and sometimes white light (for the colours of the Tricolour). That was highly unusual for the time. In addition to seeing the play, I would have been interested to witness the audience’s reaction.

We want to continue expanding our notion of equality in order to be more aware of potential and actual barriers and exclusions.

You recently became Head of Equal Opportunity and Diversity at the Cluster. How do you approach this task and what will be your priorities in this new role?

At the Cluster, we’ve tried to build and maintain a structure that removes or at least reduces barriers, as far as possible allows for equal opportunities, and remains open to the work that always still needs to be done. We are lucky to have a great new colleague in the Equal Opportunity Office, Mariapaola Gritti, who, besides her programmatic work, takes care of the everyday business of advising Cluster members and connecting them with the relevant services. Mariapaola and I are thankful to our predecessors, Sabine Kienitz and Johanna Seibert, for setting things in place. We maintain an emphasis on gender equality and the compatibility of family and career. But we also want to continue expanding our notion of equality in order to be more aware of other potential and actual barriers and exclusions.

We believe that fostering diversity is key to achieving not only excellence in research, but also personal and social wellbeing, growth, and resilience within and beyond academia. We already have offered a mentoring programme for female postdocs in the past and plan to expand this with respect to diversity, for example with a programme for our international postdocs. We’re also considering developing a peer (‘buddy’) mentoring system in which older doctoral students mentor 1st-semester ones. Our work ranges from trying to solve everyday obstacles to equal opportunity, for example facilitating the reimbursement of travel costs for researchers with care responsibilities, to supporting the scholarly engagement with questions of equal opportunity and diversity. We’ve initiated the ‘Guest Professorship Women in Manuscript Studies’ and we are looking forward to welcome exciting guests at the Cluster. We’re also planning a two-semester lecture series which will be entitled ‘Understanding Written Artefacts: Global Perspectives, Local Traditions, Untold Stories’, including lectures by researchers from our Cluster during the first semester, and lectures by outside guests during the second semester. Please also take a look at our new website.

Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Carl von Ossietzky, Hamburg

Do you have a favourite written artefact? What is it and what makes it so special to you?

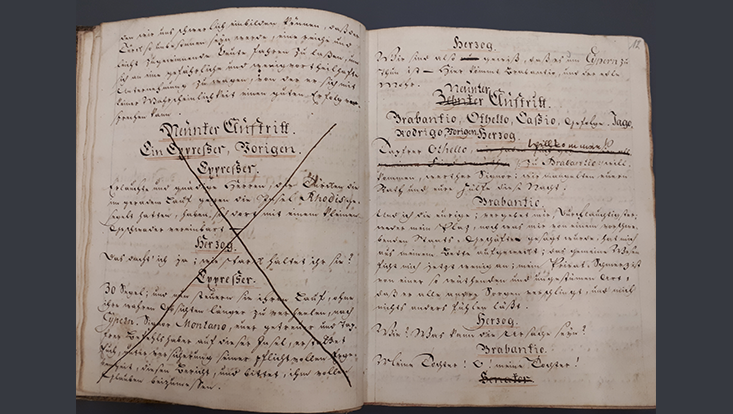

I have developed a special relationship to every prompt book I have spent some time with. Perhaps my favourite one is a 1776 prompt book for the first ever Hamburg production of Shakespeare’s Othello, which will be part of the big Cluster exhibition at Staatsbibliothek this summer.

Earlier in 1776, the company’s director, Friedrich Ludwig Schröder, had had a spectacular success when introducing the audience to Hamlet, the first ever Shakespeare in Hamburg and starting point of the German Hamlet-mania. However, Schröder had adapted the play to the customs and perceived tastes of the time. He simplified the action and changed the ending to a happy outcome. When Schröder approached Othello shortly afterwards, he tried to take things one step further: while modifying the gruesome murder Desdemona to death by stabbing instead of the erotically charged suffocation by pillow, he left the ending as such in place. To no avail: the opening night became the most prominent theatre scandal in the German speaking world. The audience left amidst loud declarations of displeasure. Urban myth has it that some female viewers even suffered miscarriages in view of the violence of the play.

The second performance was poorly attended and, thus, a financial disaster. Pragmatically, Schröder quickly reworked the play: he added a happier ending with Desdemona surviving the repentant Othello. For this outcome the whole build-up needed to be tweaked and twitched, that is, words changed and little pieces of dialogues or whole scenes cut or added. The scribe reworked the (otherwise very neat) clean copy accordingly, but with very little space since there are hardly ever any margins in prompt books of the time: sometimes by using the empty folio rectos that normally indicated the end of an act, sometimes by squeaking words between the lines, sometimes by gluing over whole pages or parts of them. The enrichment seems to have been done with great haste. The last scenes aren’t reworked at all (perhaps because they would have needed to be changed completely) but some fly leaves seem to have been inserted (and then lost). The most significant change to the play is quite inobtrusive on a material level: the stage direction ‘He stabs her’ is cut with a few plain strokes. Again and again, I have observed that the, if you will, material performance of prompt book enrichment is not always aligned with the content of the enrichment. Sometimes a rather trivial change on a content level can lead to a complicated operation on a material level (a sewed-in sheet, a wild and tangled deletion) and vice versa. The example of the Hamburg Othello is the most striking case in point. By the way, Schröder’s intervention was of little use. The revamped version was taken off the schedule soon after…

Alexander Weinstock has contributed an article on the 1776 Othello to the Artefact of the Month series. The prompt book is accessible on the home page of Staatsbibliothek Hamburg.