Traces of a Scandal

The Prompt Book for Friedrich Ludwig Schröder’s Othello Adaptation in Hamburg

Alexander Weinstock

The opening night of William Shakespeare’s Othello in Hamburg – 26 November 1776 – ended in a scandal. Even while the play was still going on, many outraged members of the packed audience left the theatre. The increasingly intense scenes of jealousy and dire intrigue – reportedly – caused any number of ladies in the audience to faint, and some even had miscarriages following their visit to the theatre. The second performance of the play was very poorly attended and this led theatre director Friedrich Ludwig Schröder, who played the diabolical Iago on stage, to revise the play – both quickly and extensively. The prompt book, which has been preserved to this day, bears testimony to this attempt to rescue a failing theatre production.

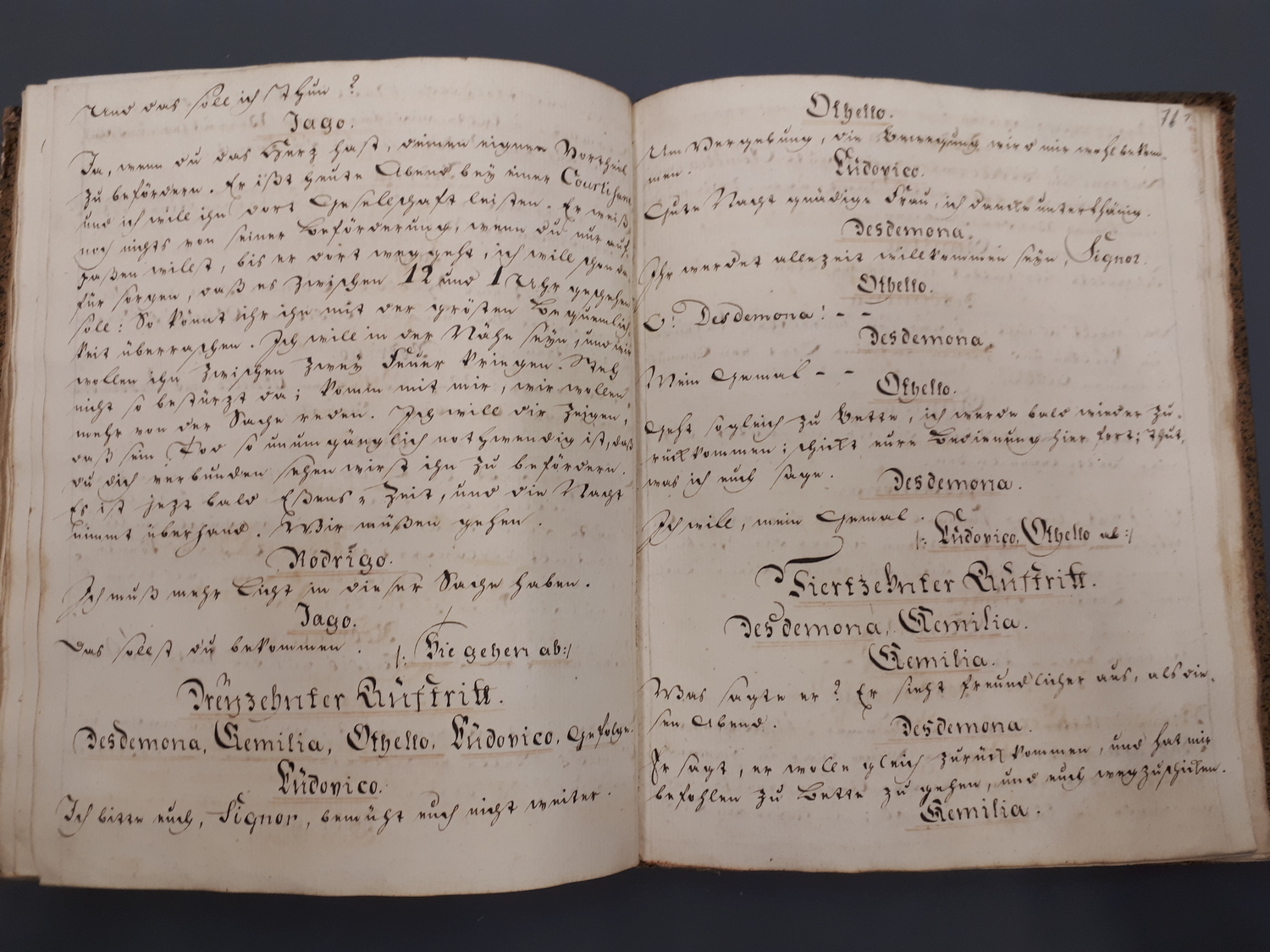

Today, the prompt book bears the shelf mark Theater-Bibliothek: 571 in the stocks of Hamburg’s Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Carl von Ossietzky. It is part of the Theater-Bibliothek (‘Theatre Library’), a collection containing roughly 3,050 playbooks from Hamburg Stadttheater, dating from 1765 to 1850, most of which were handwritten, as is the Othello prompt book which remains in its original 16.5 by 20.5 cm cardboard binding. It consists of 93 sheets stitched together with rough thread, mostly in quires of four bifolia. However, the number of pages varies whenever one act ends and another one begins: Since each new act begins at the start of a new quire, the final quire of the preceding act may vary in length. The final quire of the first act consists of three bifolia, that of the third act of only two. At the end of the second and fourth acts, a single double sheet has been added to the volume. The sheets were numbered later. Each character’s lines, i.e. the dialogue spoken by the actors, are written in Kurrent (German cursive) script in black ink, while all other parts of the text, such as character names or the details of the act, scene and plot are written in Fraktur (a blackletter script). Using different fonts is standard practice to distinguish different levels of the text from each other; in drama analysis they are known as ‘primary text’ and ‘secondary text’. In the case of our Othello, references to acts, entrances, locations, and plot, as well as the speaking characters’ names, are underlined twice in reddish ink. Two vertical pencil lines to the left and right delineate that part of the page which is to be written on (see Fig. 1), and it is quite likely that the very orderly and easily readable text has been written with the help of line marking.

In the period around 1800, prompt books were usually created by the prompters themselves, as seems to be the case with the Othello prompt book. As these were objects meant to be used during the production, expensive paper was not used. Nevertheless, these books were made to be used intensively and over a longer period of time, and it was quite possible that they would be reused in further productions. As actors would usually only receive copies of their own lines, prompt books were generally the only complete texts of the production.

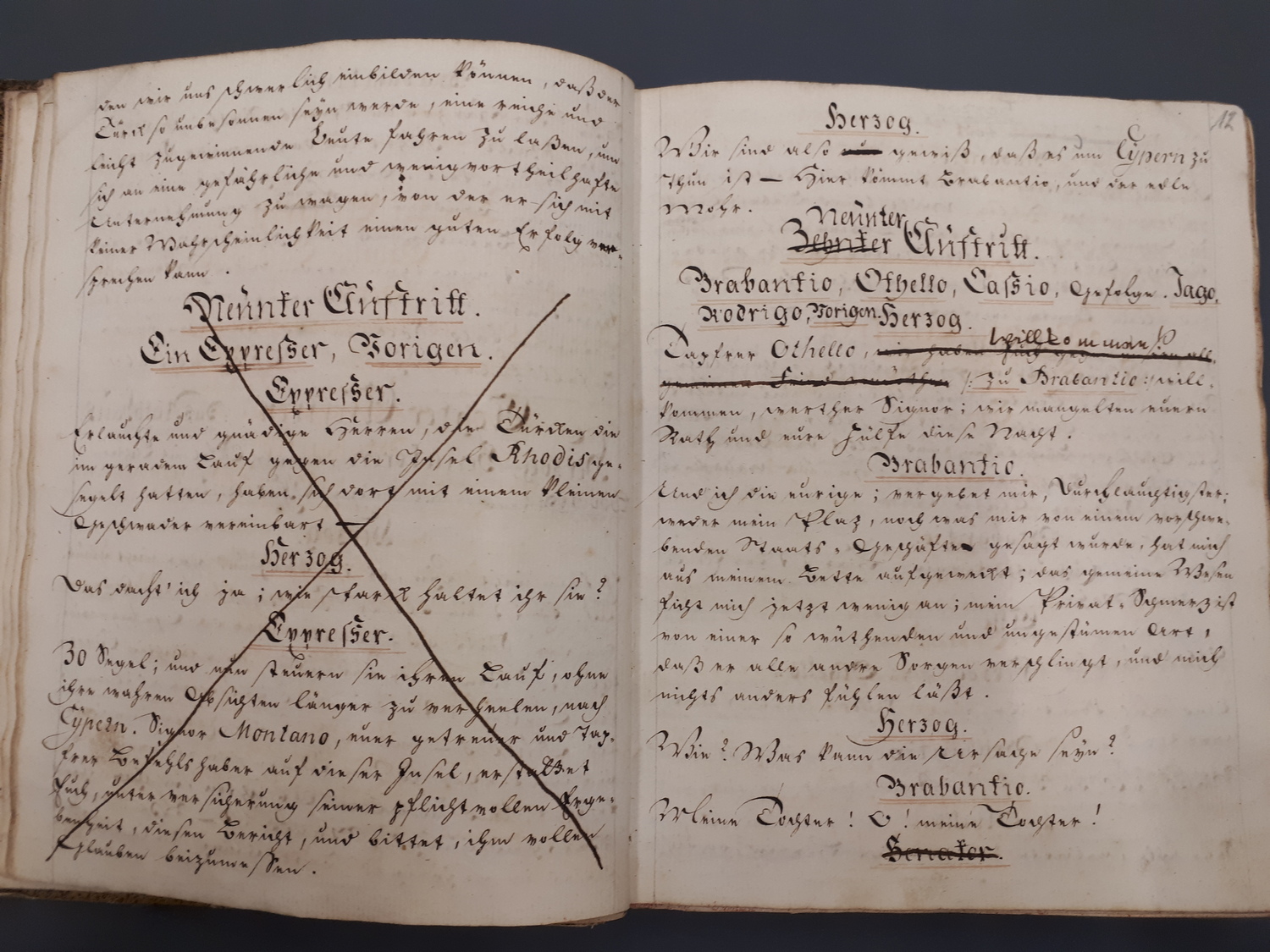

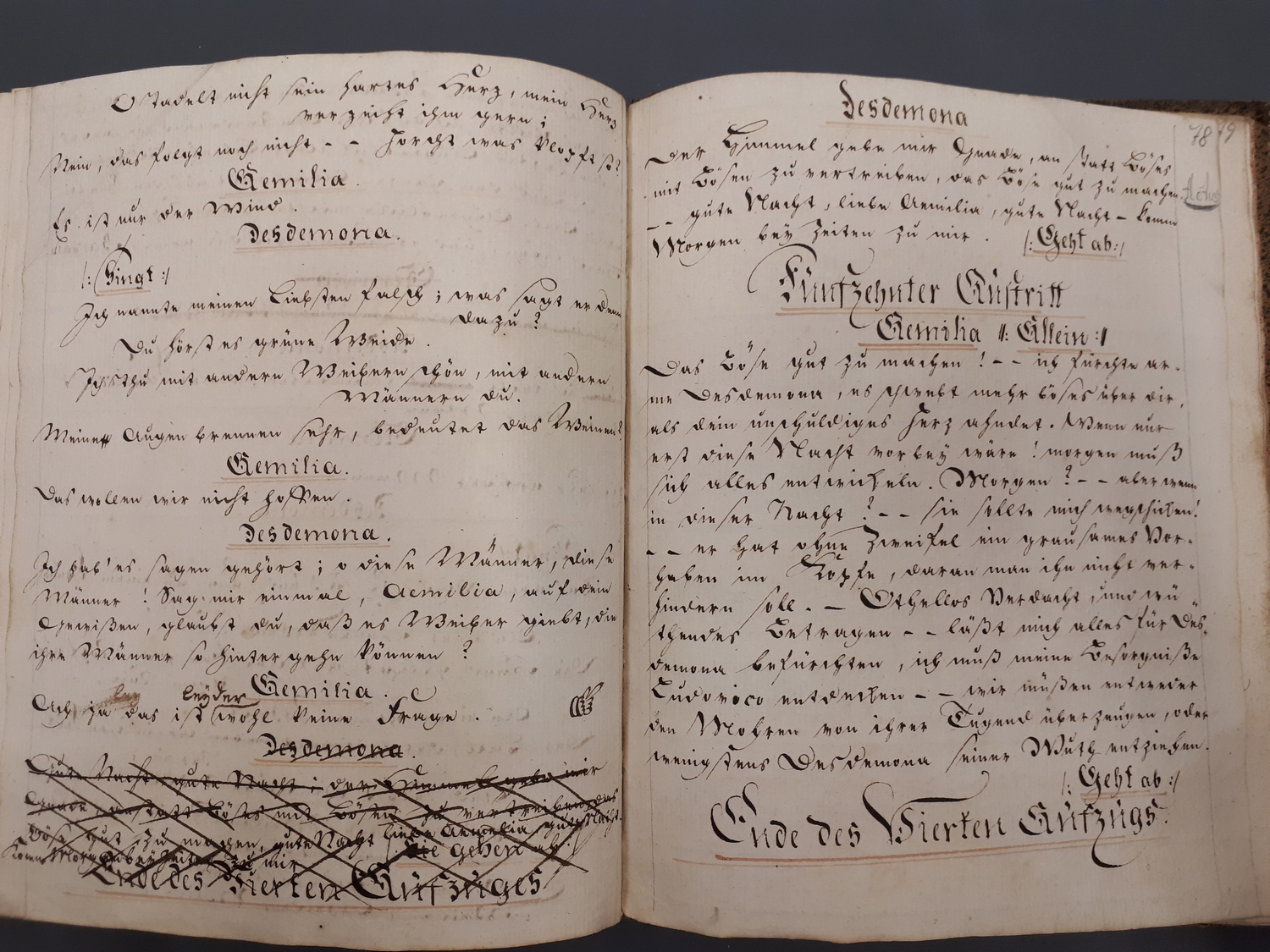

The prompter’s job was not just to provide the correct lines, they also had to keep their prompt books up to date, as the lines were likely to change during the run of a production, sometimes, as is the case with our Othello, even after the opening night. Lines and sometimes entire scenes would be cut, lines might be changed or added to. This common theatre practice manifests itself in various operations such as crossing out, pasting over and rewriting the prompt book (see Fig. 2). For the Hamburg Othello, scholars have suggested that beside the unknown prompter two other pairs of hands, including that of Friedrich Ludwig Schröder himself, were involved in making such changes.

However, even the text originally written in the prompt book is the result of a complicated adaptation process. This Othello is rightly called an adaptation, since, in order to create ‘his’ Othello, the theatre director Schröder combined the three German versions and existing reworkings of the play known at the time. These three versions themselves treated the original material with a certain amount of freedom, which was not unusual at the time.

After the scandal of the opening night, extensive rewrites took place in a very short time to save our Othello production from becoming a complete failure. Pages were glued into the prompt book, scenes were deleted and added, the plot was changed, and lines rewritten, resulting in a ‘new’ version of the play. All these changes had a single goal: To give the rather gloomy play a happy ending by averting Othello’s tragic murder of his wife Desdemona in a jealous rage.

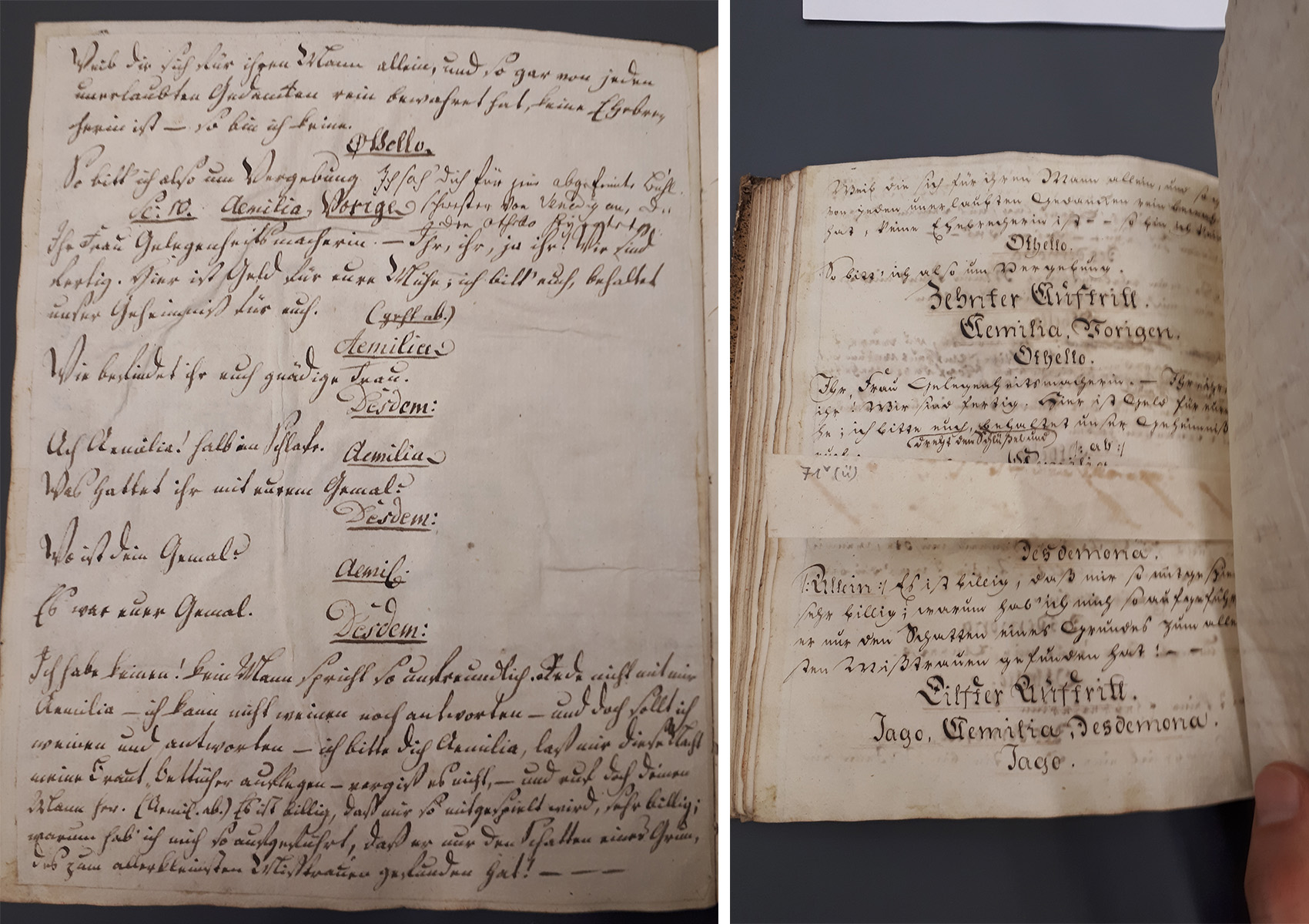

One example of a significantly changed scene can be found in Act IV, Scene 10 (see Fig. 3), as shown on fol. 71v. Restoration work by the Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek has revealed that the emphasis of this originally short – probably transitional – scene between Desdemona and her attendant Emilia has been lengthened, and was pasted over twice. First, a narrow, blank paper strip was used to cover up one of Emilia’s lines. Next to it, a note in dark ink was restored, saying: ‘12 Zeilen Platz in den Rollen’ (‘leave 12 lines free in the actors’ scripts’), presumably referring to a planned change in the text to be handed out to the actors. These changes, or at least one of them, were finally integrated into the prompt book. They were written on the second piece of paper glued into the book, covering the whole page. The type of paper used in both cases is similar to the original. While the focus of the original version is Desdemona’s self-reproach, in the new version, she urges Emilia to ‘diese Nacht meine Braut bettücher [!] auflegen’ (‘put out my bridal sheets this night’). Thus, both here and in other places the play has been changed to focus on the most critical moment of the narrative: the night when Othello kills his wife – or not, as the case may be. The visual organisation of the glued-in page suggests that these changes were carried out somewhat hastily: the notes on the scene and its characters have been added right in the middle of Othello’s lines in the preceding scene, while names have neither been underlined in red nor spelled out entirely. However, the distinction between the two types of script has been retained.

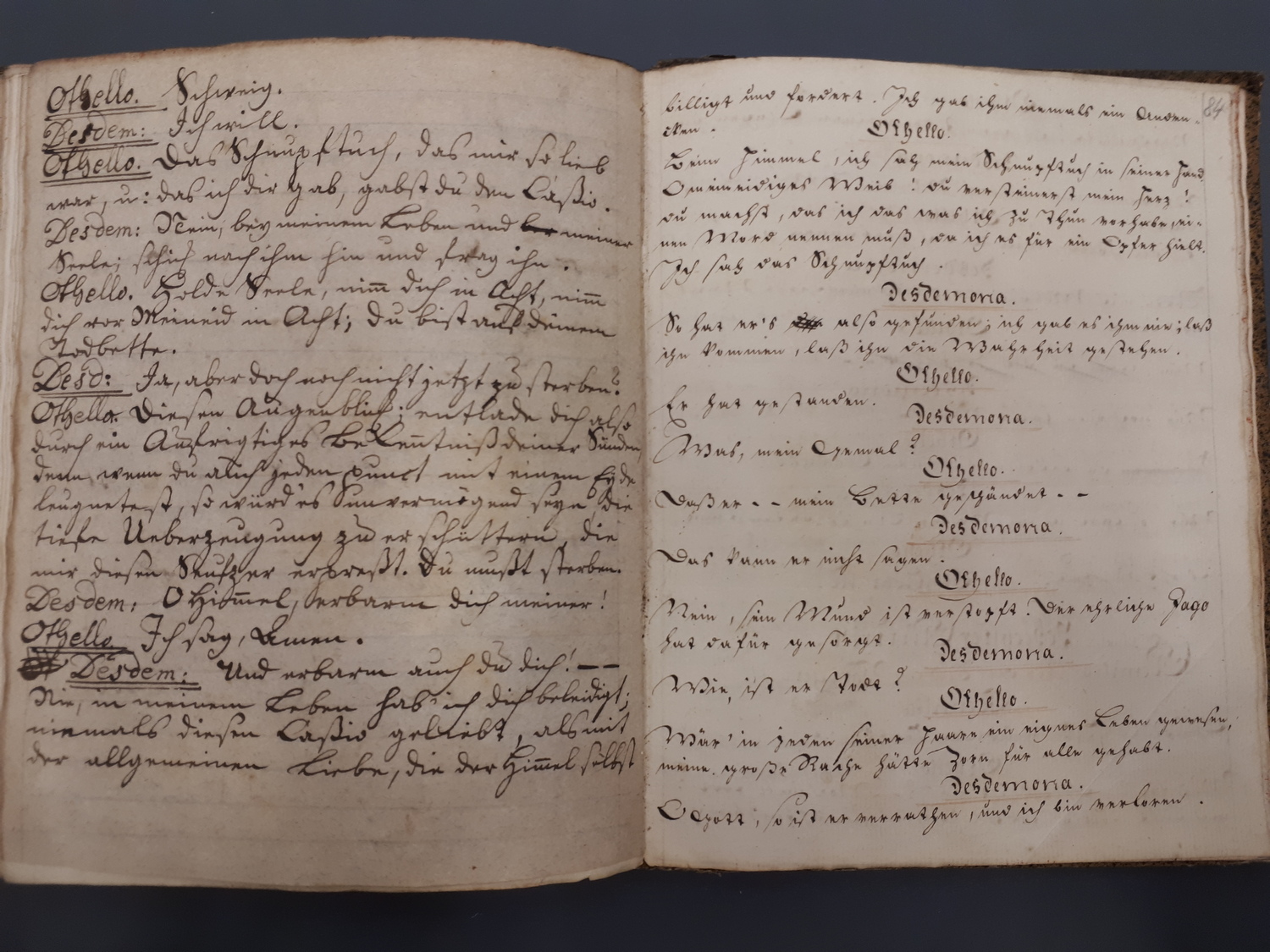

A similar change in presentation can be found at the beginning of Act V, Scene 5, written on fols 82r to 83v on slightly darker and rougher paper. On these pages, as well as the vertical lines delineating the margins, horizontal pencil lines are visible; these apparently served as a writing aid (see Fig. 4). Unlike the glued-in revisions in Act IV, however, these rewrites did not result from the scandal of the opening night. This sheet has been bound into the book as the fourth of four quires in the usual manner, and the tone of its content also differs from later revisions.

One scene serving to prepare the rescue of Desdemona, which was obviously added in later, can be found on fol. 78r, a blank page which, originally, would have been left between two acts. As a consequence of this addition, which is quite literally pointed out by a small pointing hand, the original end of Act IV, announced on fol. 77v, has been crossed out and moved to the following page (see Fig. 5). In this new version, Emilia remains on stage by herself at the end of Act IV, expressing her well-founded worries about her mistress and trying to come up with a solution in a new monologue.

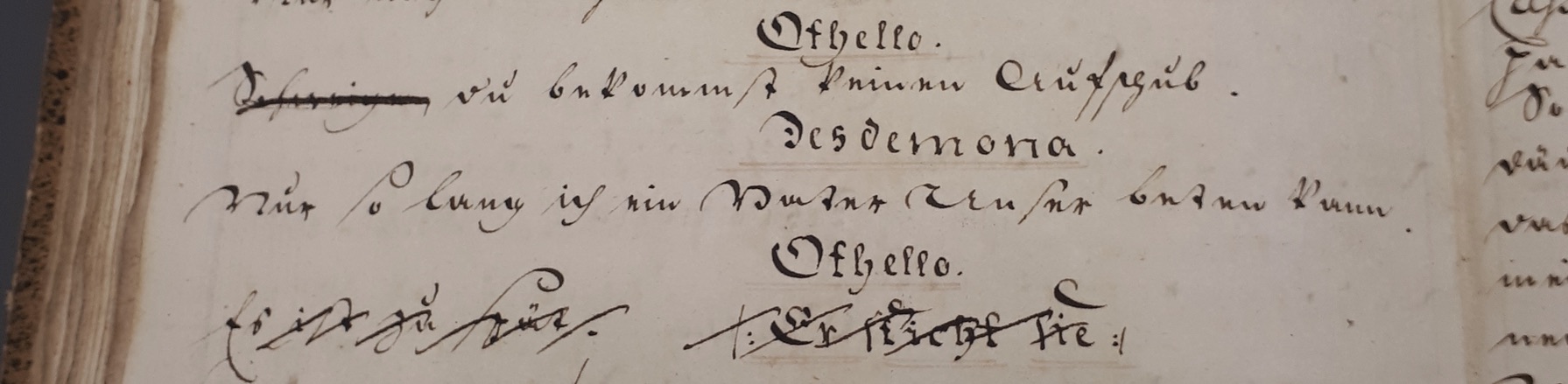

The most significant changes in content, however, follow a little later, on fol. 84v, in the climactic scene between Othello and Desdemona. In the original version, the murderous act would happen in this scene, as indicated by the stage direction: ‘Er sticht sie’ (‘He stabs her’). However, as the new version calls for Desdemona not to be murdered and for the play to have a happy ending, this act is omitted on stage – and simply crossed out in the prompt book (see Fig. 6). Six thin ink lines thus indicate the greatest possible change in the dramatic narrative.

Exactly what the new ending of the play would have looked like, we do not know. We assume that Emilia would have played a significant role, but the revisions end after fol. 84v. Scholars suppose that the revised lines handed out to the actors were either no longer added to the prompt book, or were added only on loose sheets of paper. Thus, the prompt book was not revised in its entirety, presumably because the attempt at rescuing the production by adding a happy ending failed. The revised version of Schröder’s Othello was only performed twice – and was doomed to disappear from the Hamburg repertoire entirely.

References

-

Häublein, Renata (2005), Die Entdeckung Shakespeares auf der deutschen Bühne des 18. Jahrhunderts. Adaption und Wirkung der Vermittlung auf dem Theater, Tübingen: Niemeyer.

-

Maurer-Schmoock, Sybille (1982), Deutsches Theater im 18. Jahrhundert, Tübingen: Niemeyer.

-

Neubacher, Jürgen (2016), ‘Die Aufführungsmaterialien des Hamburger Stadttheaters’, in Bernhard Jahn and Claudia Maurer Zenck (eds), Bühne und Bürgertum. Das Hamburger Stadttheater (1770–1850), Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Edition, 23–36.

-

Schütze, Johann Friedrich (1794), Hamburgische Theater-Geschichte, Hamburg: Treder.

-

Stone Peters, Julie (2000), Theatre of the Book. 1480–1880. Print, Text and Performance in Europe, Oxford [et al.]: Oxford University Press.

Description

Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Carl von Ossietzky, Hamburg

Shelf mark: Theater-Bibliothek: 571

Materials: Paper, 93 sheets, cardboard cover

Dimensions: 16.5 × 20.5 cm

Provenance: Hamburg, 1776

Reference note

Alexander Weinstock, Traces of a Scandal. The Prompt Book for Friedrich Ludwig Schröder’s Othello Adaptation in Hamburg

In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 5, CSMC, Hamburg,

https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/005-en.html