Reading Pictures, Viewing Texts

9 December 2022

Since autumn 2022, the Chair of Iranian Studies at Universität Hamburg has been held by Shervin Farridnejad, who is an expert in Zoroastrianism. Once a world religion, the faith now only has a small group of followers. They keep alive a tradition whose ideas are considerably older than its writings.

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Artikels.

Nobody can say for sure when its history first began. Sometime during the first millennium bce, possibly even earlier, a religious community was formed in Central Asia that came to be known as the Zoroastrians. Its believers invoked Ahura Mazda, the god of creation, and thus founded one of the oldest religious traditions in human history. Their faith spread across the whole of the Persian empire – until the seventh century CE, when Islam began its triumphal march across the region and marginalised Zoroastrianism. Nonetheless, it managed to survive the rigours of time in small communities scattered over Iran and India and later on in Europe and North America as well. There are roughly 100,000 Zoroastrians around the world today. Their history and culture has interested Shervin Farridnejad for many years. The scholar was recently appointed Professor of Iranian Studies by Universität Hamburg and has been working at the Cluster of Excellence on ‘Understanding Written Artefacts’ since 1 September 2022.

Intriguingly, he only came to focus on Zoroastrianism via other routes. ‘I was always particularly interested in philology,’ he says – ‘In ancient languages and texts from antiquity originating in Iran. Zoroastrian texts take centre stage in the corpus of Old and Middle Iranian texts.’ Zoroastrianism is a rare case of an ancient religion that is still alive and kicking today. We can’t make contact with the communities that once believed in Greek and Roman gods anymore, but we can with Zoroastrians, so we can compare their ancient beliefs and rituals with those they still have. What is remarkable here is the extent to which the religion practised today still draws on texts that were canonised in late antiquity. Through Zoroastrianism, a past that may seem very distant now is linked to the present. Relating the ancient world to the world we live in today is one of the most interesting aspects of his work, Farridnejad says.

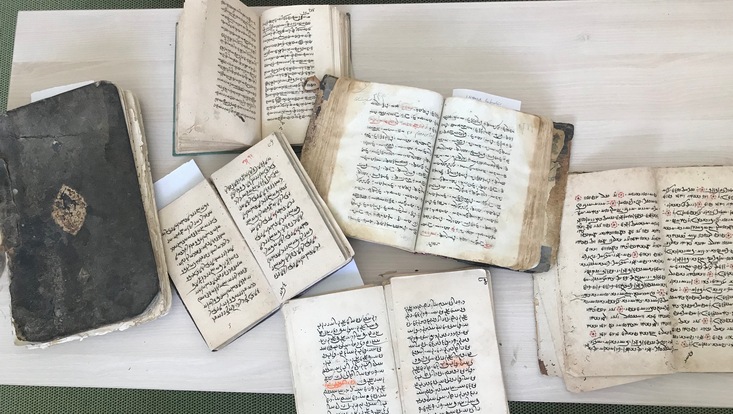

In fact, the aim of his doctoral thesis (Die Sprache der Bilder: Eine Studie zur ikonographischen Exegese der anthropomorphen Götterbilder im Zoroastrismus, published by Harrassowitz) was to link different worlds to one another, albeit in another sense. Farridnejad wanted to overcome an old and, in his view, rather unhelpful division of work: ‘Traditionally, philologists have only focused on textual matter, leaving the visual material to archaeologists and art historians. My approach, in contrast, was to try and ‘read’ the pictures and ‘view’ the texts to develop a broader understanding of texts that allows us to ask new questions.’ This holistic perspective of texts, which expressly takes their design, materiality, and use into account as well, is also what characterises the approach adopted at CSMC, which Farridnejad finds encouraging: ‘Manuscripts tell us a lot more than just what the text says. What ink was used in them? How often were they read and where were they archived? Who commissioned them to be made? Who wrote the words in the margins? Where were the manuscripts sold? When were they copied? And how were they restored? What provides us with information about all these things is their materiality. Philologists are frequently unable to discover much about them, however, as they underestimate these aspects or simply don’t have the opportunity to work together with experts from other fields such as physics or chemistry. There’s no better place to collaborate on projects than here in Hamburg.’

The question of what other elements of a manuscript are relevant apart from the text it contains – or even what a text really is – plays an important role in Farridnejad’s approach to Zoroastrianism. Religious texts had already been in circulation for over a thousand years in this religious community before anyone actually wrote them down. How can a text exist without any writing? That’s not a contradiction in itself, says Farridnejad: ‘We need to change our idea of literacy. Apart from the oldest surviving Zoroastrian written artefacts, which are around a thousand years old, no other manuscripts from before the late 13th century are left. Prior to that, there was a period lasting another thousand years from which all the written artefacts have been lost. If we go back even further, however, we come to a time when texts were passed on orally for many years in a strict, highly canonical form. By drawing on philological studies, we can show they were preserved exceedingly well over this long period.’

It wasn’t just a matter of expressing the gist of ‘the words of God’, but of passing them on exactly.

Many ancient cultures had to face the challenge of passing on their religious texts to future generations before written records of them were possible or customary. Since the proverbial devil lies in the detail, it wasn’t just a matter of expressing the gist of ‘the words of God’, but of passing them on exactly. Special techniques were developed and strictly employed just for that purpose. The Holy Scriptures of Zoroastrianism, which is called the Avesta, was passed on orally until late antiquity. A distinction was made between two different types of training for priests and thus two different kinds of priesthood. One group was trained to be ritual priests. They learnt the Avesta and liturgical texts by heart and performed daily rituals, but did not gain a command of Avestan, the sacred language of the Avesta. That was the task of those who belonged to the other group: the scholar-priests. While they understood the Zand, i.e. the translations, glosses and theological commentaries on the Avesta, the ritual priests were only supossed to use the text in a conserved form in the ritual.

‘They weren’t meant to be tempted to change anything at their own discretion,’ explains the researcher. ‘If you understand a text, then you’re in a position to alter its contents, perhaps embellish it a little here and there or leave out parts of it you don’t like or understand it differently. That was why people made sure that the areas of knowledge and activities conducted by each type of priest were kept separate, but the priests also needed each other and had to work together. It was a form of power sharing, you could say: those who sermonised using the texts were not allowed to interpret them, and vice versa. This system of mutual control worked well for a very long time.’

The success of these strategies is the reason why the ancient texts still play an important role in the religious life of Zoroastrians today and are still being used and reciprocated in their liturgy. This presents some unique opportunities for researchers as they can directly interact with members of the Zoroastrian community – and thereby intentionally or subconsciously influence the religious denomination. This interdependency between religion and research has been apparent ever since Oriental Studies was established in the 18th century, even though it is not particularly easy to grasp. If young Zoroastrian priests come to Germany today to do a PhD, for example, they are a useful source of information on the religion for Farridnejad and his colleagues. In return, they get a scholarly impression of their religion that probably has an influence on their own view of the faith. This interrelation can even become the subject of scientific studies itself.

Shervin Farridnejad’s appointment means that research into Zoroastrianism will now be a permanent activity at CSMC and Universität Hamburg. With the aid of the natural sciences and material science, he will be able to carry on viewing texts in the years to come and thus bring disciplines together that seem to have so little to do with each other at first glance, yet so much upon closer inspection – just like the link between the past and present.

Shervin Farridnejad

has been Professor of Iranian Studies at Universität Hamburg since 2022. At the Cluster of Excellence 'Understanding Written Artefacts', he is the head of the MA programme 'Manuscript Cultures' since the winter semester 2022/2023. Before moving to Hamburg, he was a lecturer at the Institute for Iranian Studies at FU Berlin.