5 Questions to...Thies Staack

14 November 2022

In our series ‘5 Questions to…’, members of CSMC chat about their background, what motivates them, and their favourite written artefacts. This time, we talk to Thies Staack, a sinologist studying two very different kinds of Chinese manuscripts: ancient legal texts and late-imperial medical recipes.

Thies Staack, please tell us a little about yourself.

I grew up in a small town in Northern Germany, between the Kiel Canal and the North Sea. After secondary school, I moved to Hamburg to study Sinology. At some point, my future doctoral advisor Professor Michael Friedrich proposed that I take courses on ancient Chinese manuscripts with Dr Matthias Richter (now professor at the University of Colorado Boulder). These courses sparked an interest in handwritten things that has stuck with me ever since. For roughly ten years – starting with my MA thesis throughout the doctorate and beyond – I worked on ancient bamboo and wood manuscripts, predominantly from the context of law and administration. In my doctoral thesis (2015), written at the graduate school of CSMC, I developed methods for the reconstruction of ancient bamboo scrolls. The thesis focussed especially on formerly neglected evidence that could be drawn from the material features of the individual bamboo slips from which these scrolls were produced (e.g. imprints of ink). I continued to work on the codicology of ancient Chinese manuscripts as a postdoc at the SFB ‘Material Text Cultures’ at Universität Heidelberg under the guidance of Professor Enno Giele. In 2019, when I felt the need to broaden my view beyond ancient China, I got the chance to join the Cluster and to dive into an entirely new field with a project on 19th- and early 20th-century Chinese medical manuscripts from a collection in Berlin.

What are you currently working on?

Recently, I have been revising two papers. The first is devoted to a group of 19th- and 20th-century manuscripts that include material copied from a medical standard work that was commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor and published in print in 1742. The paper comprehensively analyses the content and material features of the manuscripts and argues that, rather than being mere ‘copies’, the manuscripts served important didactic and epistemic functions. The findings also shed light on the lasting importance of manuscripts in the age of print, which is one of the core topics of the Cluster’s working group ‘Facing New Technologies’ in which my project is situated. The second paper is based on a presentation given at the 2021 CSMC workshop ‘Tied & Bound’. It outlines typical features of ancient Chinese bamboo and wood scrolls, addressing aspects such as the preparation of individual slips before tying them together to form a scroll, the materials used for the binding strings, different techniques by which the strings were applied to the slips, et cetera.

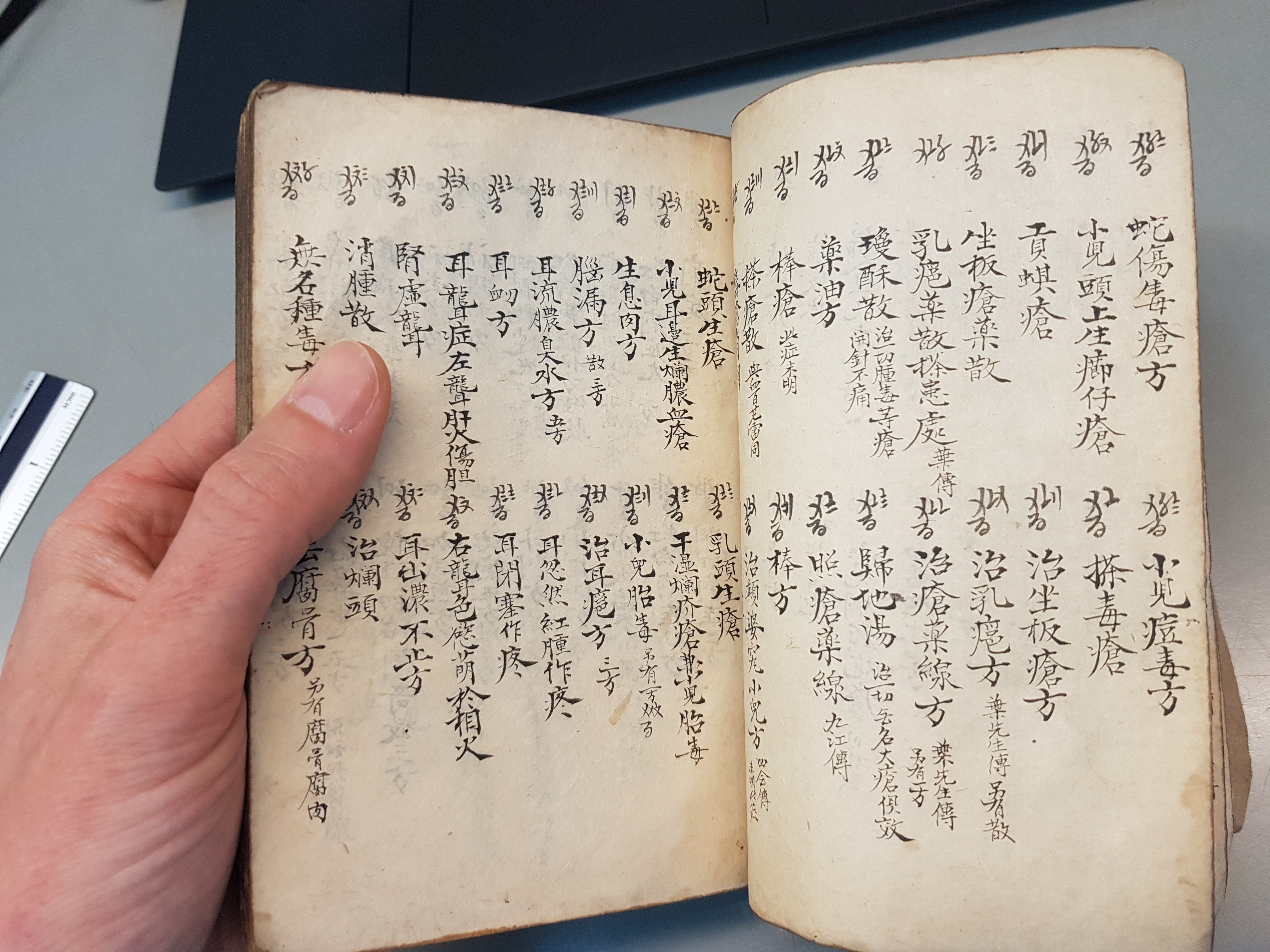

Besides these papers, I continue to work on my book project. Centred on a particular recipe book from 19th-century Canton (see below) and its wider context, it aims to contribute to a social history of collecting and exchanging recipes in late imperial China.

Many of the questions and problems of the present can only be solved with a view to developments that took place much earlier in Chinese history.

Two of your main research topics are early Chinese law and medical literature from late imperial China. How and why did these topics in particular emerge as your interests?

I came to early Chinese law by chance when in 2011 I had the opportunity to join a DFG project devoted to 3rd c. BCE legal manuscripts from the collection of Yuelu Academy, Changsha. For a couple of years, I had been fascinated with ancient China in general, and ancient manuscripts in particular, but the field of Chinese law was new to me at that point. Fortunately, my senior colleague in the same project was Dr Ulrich Lau, one of the few specialists on ancient Chinese law outside China, and I profited greatly from his expertise and guidance. Studying collections of exemplary legal cases or statutes and ordinances together, I not only learnt many interesting details about tomb robbers, heritage disputes, or underage counterfeiters of official documents. The highly formulaic language of administrative and legal documents also became more and more familiar – even likable! – and I have been interested in these aspects of early Chinese culture ever since.

When I set out to work on medical literature from late imperial China in 2019, this not only meant a jump across thematic fields, but also across a timespan of roughly 2,000 years. The main reason behind this endeavour was that a vast collection of more than 1,000 Chinese medical manuscripts – gathered over the course of four decades by Paul Ulrich Unschuld – was conveniently located in Berlin, and research on it had just begun. When working on ancient manuscripts, I normally had to base my research on printed or digital reproductions, as inspection of the original manuscripts is rarely possible. The Berlin manuscripts, however, could be inspected first-hand – a circumstance that made them highly attractive to me. In hindsight, with the severe restrictions on international travel in the past few years due to the pandemic, this turned out to be a fortunate choice. Despite the huge differences between these materials and the ones I had worked on before, the common denominator is the fact that they are all manuscripts. Hence, although it took considerable time to get acquainted with medical terminology and the entirely different historical background, I did not have to start from scratch in every respect.

Is your work affected in any way by the increasing tensions between China and the West? Do these tensions, in your view, have an impact on the public perception of Sinology as a subject?

As my own research focuses on late or even early imperial rather than contemporary China and is also not concerned with any politically sensitive topic, I have not experienced direct negative effects on my work. In my view, the mentioned tensions between China and the West have certainly led to an increasing public interest in contemporary China, especially its geopolitics, in recent years. In the future, this might have an impact on our field insofar as research and teaching about China could become even more focused on contemporary China than is already the case at many universities. I hope that this will not entail further neglect of traditional China, because many of the questions and problems of the present can only be solved with a view to developments that took place much earlier in Chinese history.

Do you have a favourite written artefact? What is it, and what makes it so special to you?

At present, my favourite written artefact is the recipe book Slg. Unschuld 8051 from 19th c. Canton, which I have introduced at some length in a contribution for the series ‘Artefact of the Month’. It mostly fascinates me because it seems to have been used and continuously updated for at least 100 years by a series of owners. In addition, many of the recipes collected in it are attributed to specific persons who are mentioned by name; sometimes even an address is provided. In contrast to many other manuscripts from the same collection, Slg. Unschuld 8051 therefore provides a wealth of information about its original temporal and spatial setting. This makes it a perfect candidate for a case study on how medical recipes were collected and exchanged in late imperial China, and which role(s) written artefacts played in this context.