Collecting Recipes in Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century Canton: Tang Tingguang’s Recipe Book

Tang Tingguang’s Recipe Book

Thies Staack

At some time in the first half of the nineteenth century, a person by the name of Tang Tingguang 唐廷光 roamed the streets of Canton, Southern China. Travelers, soldiers, monks, and beggars walked the wide avenues and narrow alleys lined with the shops and market-stalls that offered anything from books and writing brushes, to fine silk fabrics, delicate sweets, or rice and tea. Tang, however, had something different in mind. For some time, he had gazed on the Sangsheng sweet shop a few streets away with a certain envy. Its owner would hand out pills to customers for the treatment of bruises, and these pills seemed to be wondrously effective. Tang sent his disciple Li Binghe 李秉和 to obtain a copy of the recipe, hoping that he would finally be able to add it to his recipe book. But would he be successful?

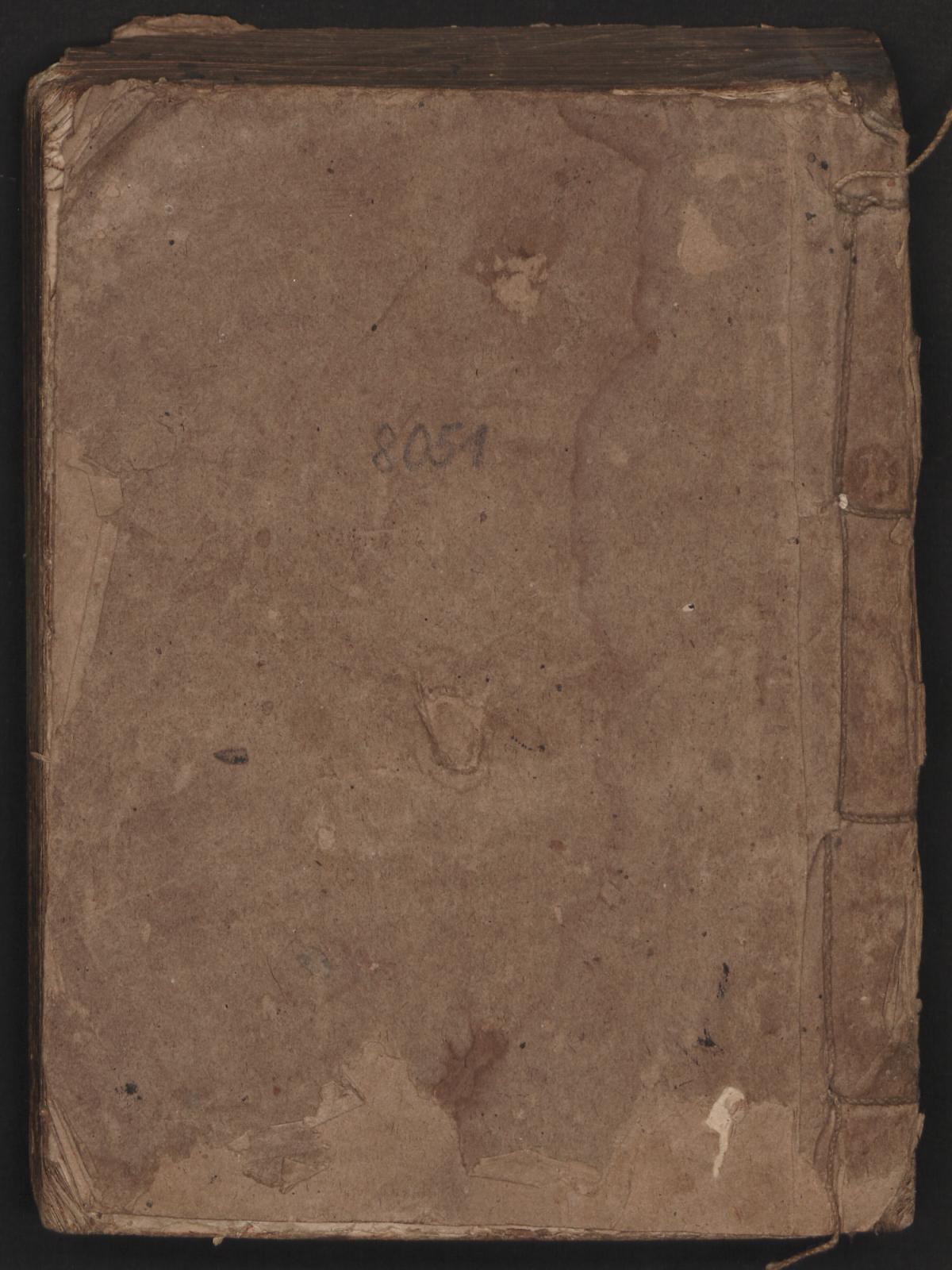

Today, Tang’s recipe manuscript is part of the Unschuld collection of Chinese medical manuscripts housed by the State Library of Berlin under the shelf mark Slg. Unschuld 8051. With 229 folios, the thread-bound paper codex is among the most voluminous manuscripts in the whole collection, at least in terms of page count. However, judging from its size – it is only 15.2 by 11.7 cm – it is rather small compared to most other recipe manuscripts; indeed, it is quite inconspicuous, threadbare and timeworn, and without a title (Fig. 1). The manuscript is a compilation of medical recipes that were recorded with brush and carbon ink and were to be used against various ailments ranging from leprosy, to haemorrhoids, tooth ache and hair loss. Originally compiled in the first half of the nineteenth century, the collection was expanded in various stages until the early part of the twentieth century.

The number of recipes recorded in the manuscript is enormous, roughly 800. A single manuscript page typically contains two or three recipes, depending on their length. Usually, the recipes consist of a title, a list of ingredients including their amounts, and finally instructions on preparation. The following recipe may serve as an example (fol. 197b):

No. 447: Ulcers in the mouth or on the tongue

Amur cork tree bark: 8 candareens (c. 3 g); rhizome of goldthread from Sichuan: 5 candareens (c. 2 g); Wuyi tea: 1 candareen (c. 0.4 g). Grind to powder and apply to the ulcer.

Some of the recipes might seem rather strange to a modern reader (fol. 144b):

No. 287: Good recipe against food stuck in the throat

Take one stinking dead cat, burn it on coals, let the patient smell the odour of this, and he will be cured.

Most recipes, however, describe less ‘eccentric’ ways of treatment, involving pastes, pills, powders or decoctions produced mainly from plant, animal or mineral ingredients.

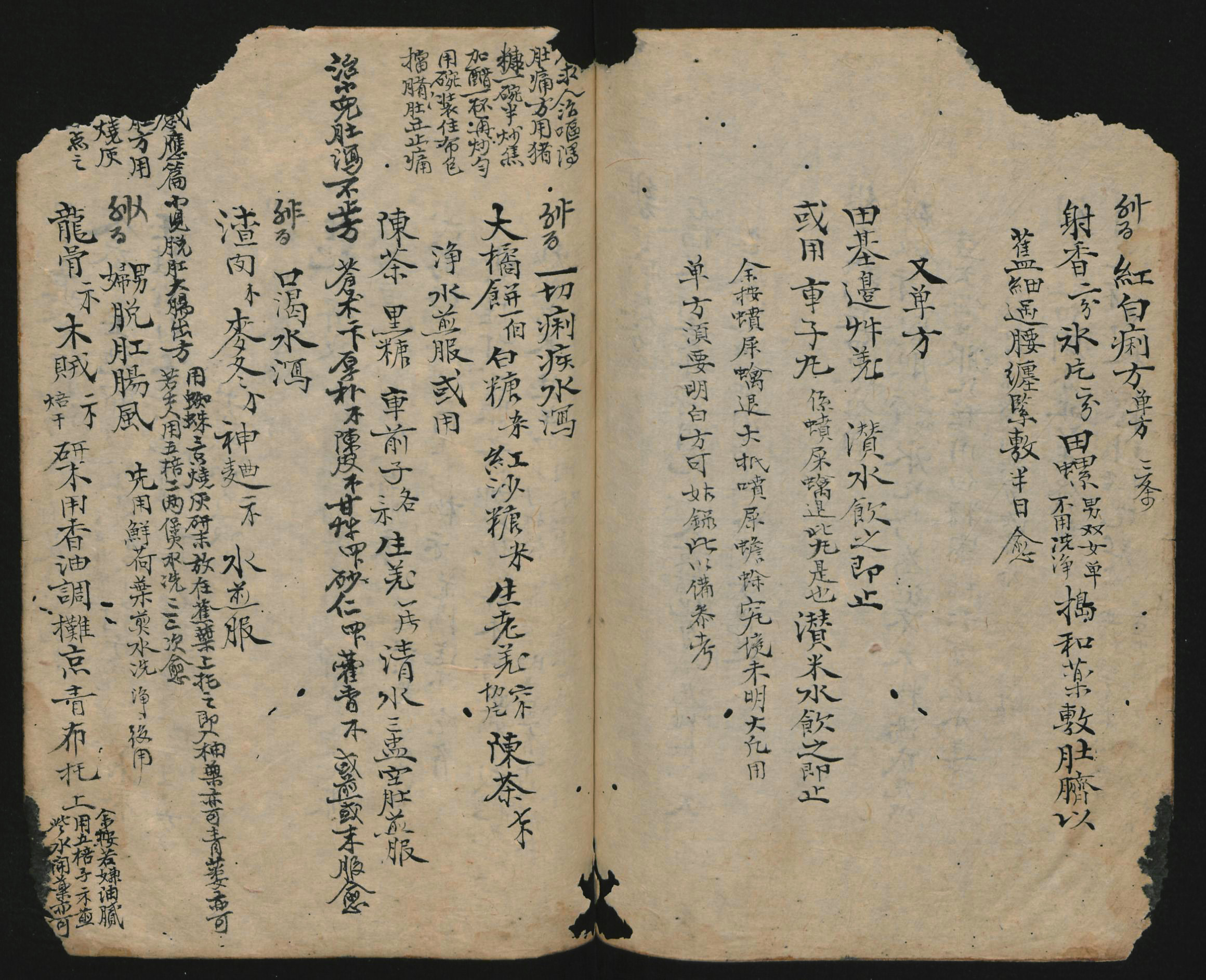

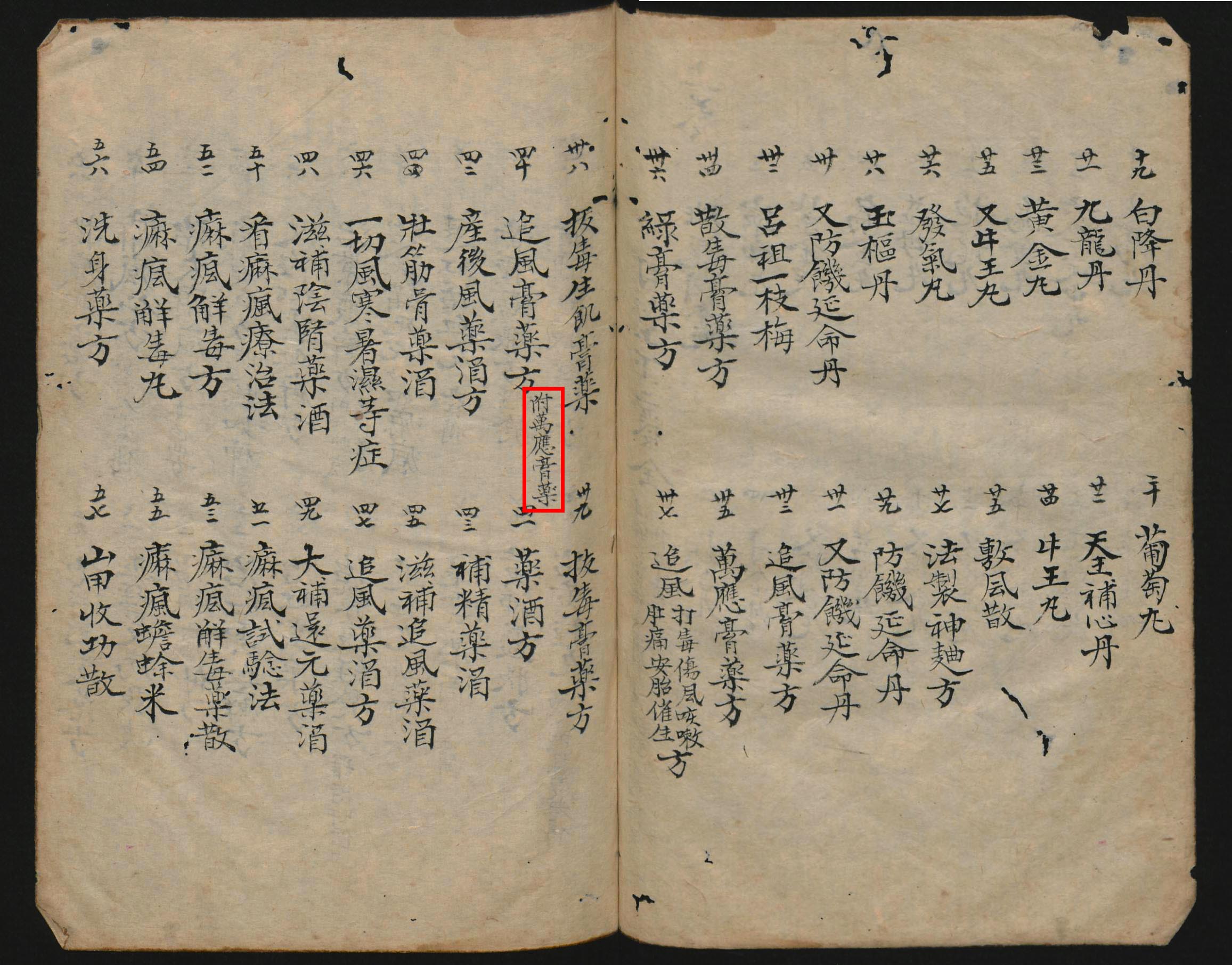

Even a brief inspection of the manuscript shows that several hands were at work (Fig. 2), and closer observation reveals some of the details of the ‘life’ of this manuscript. The earliest entries (more than 500 recipes) can be attributed to Tang Tingguang who left his name along with one of his comments (fol. 158a). Tang seems to have conceived the volume as a reference work, because not only did he arrange the recipes into sections according to the illnesses or ailments they were supposed to treat, he also furnished his collection with a table of contents (fols 11a–30a), listing the recipe titles and assigning a number to each recipe. This greatly facilitates ‘navigating’ the volume (Fig. 3). In fact, the table of contents includes recipe entries for two volumes, the second of which must have been a separate manuscript now lost. The way the recipes are arranged and made accessible suggests that Tang was a medical professional – most likely a physician or pharmacist. This impression is substantiated by various comments which he added to individual entries. They often relate to the effectiveness of the recipes and suggest modifications probably based on Tang’s own experience. Other annotations reveal some of the tricks Tang used to make a higher profit. For example, he describes a way of adding colour to a medicine in order to conceal the fact that it consists of cheap and widely available ingredients. In some cases, he mentions that he had to go to great lengths in order to obtain a particular recipe, or that a recipe should be kept confidential at all costs, or, again, that it is ‘suitable for making money’ (fol. 64b). All this suggests that Tang Tingguang was dependent on the recipes he collected for making a living.

One of the most remarkable features of Tang’s recipe collection is that for a large number of the recipes (roughly 25%) he noted the sources, and their variety is quite astonishing. Not only does he list books – including the medication list of a renowned Canton pharmacy first printed in 1804 –, he also mentions relatives, friends, colleagues or acquaintances. Apparently, he received recipes from the owners of various shops as well as from the monks of three different Buddhist monasteries in the city. As Canton streets or other place names are often mentioned in conjunction with the name of a person or shop, it is possible to narrow down Tang’s main area of activity. Most of his recipe sources are situated in the southern part of the walled city or in Canton’s Western suburbs (Xi guan 西關). Here, one street in particular – ‘Physic Street’ (Jiang lan jie 漿欄街) – was famous for its large number of medicine shops (Fig. 4).

Collecting recipes seems to have been a long-term project for Tang; there is certainly some evidence of this in the manuscript. In fact, the manuscript described here was not even the first recipe collection Tang produced. At various places in the volume, reference is made to an ‘old volume’ (jiu ben 舊本) which appears to have been the basis on which the present manuscript was compiled. Thus, it is highly likely that this manuscript started as a clear copy of an earlier recipe collection that he had been updating for some time. Furthermore, Tang obviously anticipated later additions, and left several blank pages between the sections devoted to different illnesses, adding recipes himself at the end of several sections. This observation is evident in the table of contents where these later recipes were occasionally added (Fig. 3).

Beside Tang Tingguang’s, at least four other hands can be identified in the manuscript. All of them added recipes to the collection, but only two seem to have been the hands of medical experts. These two not only added recipes at the appropriate places – in proximity to other recipes for the treatment of the same ailment – but also commented on recipes on the basis of their own experience. At least one of the two hands, which added recipes between sections as well as in the margins or between lines (see the additions visible on the left-hand page in Fig. 2), may have been a relative of Tang Tingguang, most likely his son. This relationship is suggested by the fact that one of the recipes recorded by this hand is attributed to someone from the Tang family, a certain Tang Wankuan 唐萬寬, who is referred to as ‘older brother’. At some point in its life, the manuscript seems to have been obtained by someone outside the Tang family, or at least by a person who does not seem to have been a medical specialist. Later hands added recipes that stray from the realm of medicine, for example on how to produce hair pomade or on how to recharge old batteries. Some of these later additions cannot have happened before the 1920s, because they include a recipe copied from a Republican period Canton newspaper.

Although we still lack many details about the history of this manuscript, it is clear that the manuscript was used and constantly expanded for at least 100 years. Originally produced by a medical specialist, it seems to have moved through the hands of several other owners, although it seems to have remained in the Canton area. Not only does the manuscript attest to the fact that hand-copied recipe collections such as this one were used well into the twentieth century, it also casts a spotlight onto the vibrant culture of recipe exchange and trade that must have taken place in Canton during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Much of the social history of recipe collecting at the time remains to be discovered. However, what we do know from a record in Tang’s manuscript is that his attempt to obtain the recipe from the Sansheng sweet shop was indeed successful. As it turned out, the recipe was entirely identical with one that Tang had already recorded (fol. 98a). But for him, this was not so much a disappointment as an additional proof that this recipe was ‘100% effective’, as he noted next to the recipe.

References

- Gray, John Henry (1875), Walks in the City of Canton, Hongkong: De Souza & Co.

- Miles, Steven B. (2006), The Sea of Learning: Mobility and Identity in Nineteenth-Century Guangzhou, Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press.

- Thomson, John (1873), Illustrations of China and Its People: A Series of Two Hundred Photographs with Letterpress Descriptive of the Places and People Represented, 4 vols, London: Sampson Low, Marston Low, and Searle.

- Unschuld, Paul Ulrich and Zheng Jinsheng (2012), Chinese Traditional Healing: The Berlin Collections of Manuscript Volumes from the 16th through the early 20th Century (Sir Henry Wellcome Asian Series, 10), 3 vols, Leiden: Brill.

- Zhang Ying (2019), ‘Healing, Entertaining, and Accumulating Merit: The Circulation of Medical Recipes from the Late Ming through the Qing’, Frontiers of History in China, 14/1: 109–136.

Description

Museum/Collection: Unschuld collection, State Library of Berlin

Accession number: Slg. Unschuld 8051

Material: paper, 229 folios, stab-stitched thread binding (xian zhuang 綫裝)

Measurements: c. 15.2 × 11.7 cm

Provenance: unclear (place of production probably Canton/Guangzhou, China)

Language: Chinese

Period/Date: Late Qing to Early Republic (nineteenth to early twentieth c.)

Copyright notice

Fig. 1: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Slg. Unschuld 8051,

http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000603200000001.

Fig. 2: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Slg. Unschuld 8051,

http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000603200000446 and http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000603200000447.

Fig. 3: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Slg. Unschuld 8051,

http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000603200000024 and http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000603200000025.

Fig. 4: Thomson 1873, vol. 1, plate xx, World Digital Library.

Reference note

Thies Staack, Collecting Recipes in Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century Canton: Tang Tingguang’s Recipe Book. In: Wiebke Beyer, Karin Becker (eds): Artefact of the Month No 15, CSMC, Hamburg, https://www.csmc.uni-hamburg.de/publications/aom/015-en.html