The Impulse to WriteOn Axel Malik's 'Exceeding Colophon'

2 August 2022

On the CSMC's Open Day, Axel Malik published his brochure 'Exceeding Colophon'. In his preface, art historian Bruno Reudenbach explores some basic questions raised by Malik's art: 'Is what he creates really "writing" as such? If "writing" is the wrong term for it, which word should we use instead?'

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Vorworts

Axel Malik has been linked to our Cluster of Excellence 'Understanding Written Artefacts' since 2021 when he became our Artist in Residence. Initially, the encounter that was intended to take place between science and art could only be achieved digitally due to the pandemic: a piece of artwork entitled Increasing Countdown has been featured on the Cluster’s website since September, which is basically a horizontal band of characters running across the screen. Growing in length by a character a day, it won’t stop increasing until 27 September 2023 when the Cluster’s official conference begins. Following on from this virtual creation, Axel Malik has now produced Exceeding Colophon, a tangible work created to celebrate the tenth anniversary of CSMC’s inception at Universität Hamburg.

One might describe Axel Malik as a ‘writing artist’ – but is what he creates really ‘writing’ as such? Is his artistic activity, which he calls ‘the scriptal method’, the same thing? If ‘writing’ is the wrong term for it, which word should we use instead? Questions of this kind quickly come to mind as one leafs through the brochure on Exceeding Colophon, which can be regarded as a kind of miniature exhibition in itself.

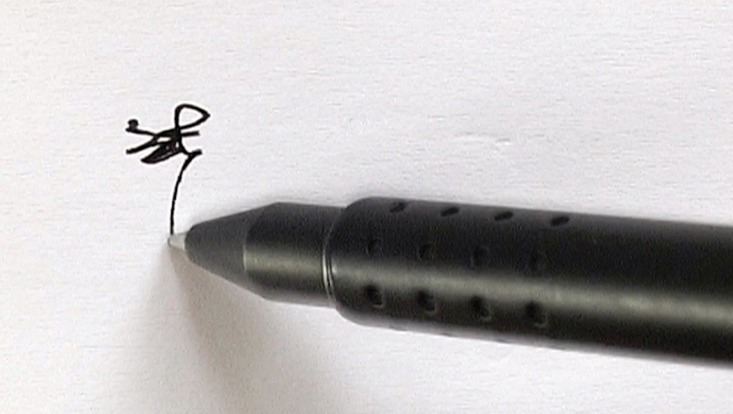

Axel Maliks adds characters in rows next to or underneath each other in ever-changing variations. Usually, each of the characters are clearly separated from neighbouring ones; they only join up in the style typical of continuous handwriting occasionally. Even so, the unconnected characters, which appear just like printed text, are clearly recognisable as being ‘written’ by hand.

None of the characters are ever repeated in this ever-expanding world of writing

What these characters have in common is that none of them follow the rules that normally apply to characters and letters, the shapes of which are predefined and readily recognisable, so they can be read and have a specific meaning. The artist’s characters, on the other hand, stem from a spontaneous, constantly changing impulse to move and write with which he fills one page after the other in formats ranging from large-sized folios to small books reminiscent of diaries. Consequently, none of the characters are ever repeated in this ever-expanding world of writing composed of thousands upon thousands of spontaneously created figures. As a result, they don’t actually form any proper words or have any specific meaning; they are not characters in a conventional sense as they do not denote anything. This kind of writing can’t actually be read at all; it’s incomprehensible – but far from being just naïve scribbling.

So what is it that makes us – quite rightly – think of ‘writing’ when we first see this piece of art? The association in our minds is triggered primarily by the artistic arrangement of the work as a whole and the formal context it creates. The sequences of characters Axel Malik has created are all roughly the same size, which immediately makes one think of lines of writing of the same length and height. Surrounded by a wide margin on a rectangular surface, the effect is just like the page of a book.

As a matter of fact, books – a category that also includes this small brochure, of course – are one of the formats that the artist most often employs. Books and manuscripts are usually filled with writing and are meant to be read – expectations that Axel Malik deliberately undermines, albeit without giving up the impression that we are dealing with real writing.

As artistic statements on the ontological status of writing, Axel Malik’s works thus touch on fundamental phenomena

The thing is, however, his ‘writing’ is not visualised speech as such – there is nothing to read in this case, but all the more to see: characters that are sometimes drawn with a broad stroke and sometimes using the finest of lines, some letters very large, others tiny, in varying rhythms, drawn close together or wide apart, sometimes arranged horizontally and sometimes in vertical lines on a background with written areas and blank fields in differing proportions to one another.

Properties of writing that are often overlooked are demonstrated and even explicitly pointed out this way, namely its visual qualities and aesthetic values, not to mention its figurative qualities and imagery. As artistic statements on the ontological status of writing, Axel Malik’s works thus touch on fundamental phenomena that are of relevance to Written Artefacts.

Exceeding Colophon has a place of its own in Written Artefacts by virtue of its form as a bound manuscript, the written pages of which can be turned over. But not just that. By employing the Latin words explicit liber (‘here ends the book’) in clearly legible type, it makes a specific reference to medieval manuscript culture as this is the fixed wording medieval scribes once used to indicate where the book they had been working on ended.

The title, Exceeding Colophon, also alludes to a phenomenon familiar to many manuscript cultures: colophons are written notes in which scribes provided information about themselves, the date and place of writing, who had employed them and why, or they briefly outlined other such circumstances, regardless of what text the manuscript actually contained. Varying this tradition, Axel Malik uses the last page to provide his brochure for this festive occasion with a kind of signature, a stamp and rows of characters he wrote down in various ways.

This point and the enigmatic title of the work, Exceeding Colophon, which plays on the scientific term, mark his own artistic sphere, which is adjacent to science, one could say, but not exactly the same thing.