5 Questions to...Cécile Michel

11 February 2022

In our series, '5 Questions to…', members of CSMC chat about their background, current work, what motivates them, and about their favourite written artefacts. In this episode, we talk to Cécile Michel, an Assyriologist who is constantly on the move: between Paris and Hamburg, the past and the present.

Cécile Michel, please tell us a little about yourself.

As an Assyriologist, I work on the history and the archaeology of the Ancient Near East, a vast area where cuneiform script was developed and used for more than three millennia. I am French and a Senior Researcher at the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) where I am part of a joint research unit linking CNRS and the Universities Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and Paris Nanterre. It brings together archaeologists, philologists, and historians of Antiquity and the Middle Ages who are working all over the globe.

Besides doing research, I am teaching mainly MA and PhD students, but I am also organising intensive courses on Akkadian language open to all. I never supervise more than one or two PhD students at a time to provide them with the best possible support. Above all, I try to make sure that they get a contract after submitting their thesis because times are really difficult for young researchers. To help early career researchers, I organise master classes for candidates for a European Marie Curie grant every year. Currently, we are lucky to have six laureates on our team.

In addition, I am very involved in the administration of research. For ten years, I was a member of the National Committee of Scientific Research, evaluating labs, journals, and researchers. At CNRS, I was also a jury member for the hiring of permanent positions and headed the Scientific Council of the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, reflecting, among other things, on the prospective of research. Now, I am a scientific integrity officer in charge of all the dossiers concerning these fields. Last but not least, I engage in outreach activities for a wider audience.

In 2015, I was fortunate to join CSMC thanks to an invitation from its director, Michael Friedrich. The many meetings and retreats that set the basis for the Cluster of Excellence were particularly rich, both scientifically and personally. Within CSMC and the Cluster, I learned a lot by setting up projects with colleagues from very different disciplines, including the natural sciences. The atmosphere is excellent, stimulating, and very constructive.

I am also travelling a lot, for example to Turkey, where I work on cuneiform tablets and participate in the archaeological excavations at Kültepe in Central Anatolia. I have always considered it a great privilege to make a living from my passion.

What are you currently working on, and how does your project contribute to your field?

I am curious by nature and being a researcher allows you to be a lifelong learner, so I am interested in a lot of things... probably too many! The body of cuneiform texts – there is over a million of them – is so rich and diverse that you can approach almost any topic. I am focusing on texts of the 2nd millennium BC written in Babylonian and Assyrian dialects, both from institutional and private buildings. I combine archaeological and iconographic sources and apply this approach, which is called experimental archaeology, to wide-ranging issues: material culture and daily life, cuneiform clay tablets, trade and society, women and gender studies, sciences (especially mathematics) and techniques, geography, chronology, and last but not least cultural heritage and ethics.

My last book deals with the lives and activities of wives and daughters of merchants living in the North of Iraq and in Central Anatolia during the early 19th century BCE. Their private correspondence and the contracts they initiated reflect the preeminent role of Assyrian women within the family and in the domestic economy as well as their contribution to long-distance trade.

Within the Cluster of Excellence, I am involved in several projects. In of them, which is carried out with Christian Schroer (Physics), Stephan Olbrich (Computer Science), and others, we aim to reveal the texts inside closed cuneiform tablets. These tablets, which contain letters and legal documents, were wrapped in a thin layer of clay forming an envelope. The sender wrote his or her name and the name of the addressee on the envelope and imprinted its surface with a cylinder seal. To read the message, the envelope had to be broken. However, many envelopes remained closed, making it impossible to read the tablets that are hidden in them. The goal of our project is to develop a high-resolution X-ray tomographic scanner to make it possible to read the hidden texts. Since cuneiform tablets cannot be taken out of the museums where they are kept, this device must be portable. There are many tablets in museums and collections around the world that will thus become readable.

For more than 40 years, scholars in this field have been working in countries at war or which do not respect human rights.

From 2014 to 2018, you were the president of the International Association for Assyriology. What did this role involve, and what are the aims of this organisation?

Assyriology is a small research field gathering at most a thousand scholars worldwide. It covers all the disciplines that deal with the study of the ancient Near East, and more specifically with the periods and geographical areas characterised by the use of cuneiform writing, including archaeology, philology, history, and art history.

For more than 40 years, scholars in this field have been working in countries at war or which do not respect human rights. The International Association for Assyriology (IAA) was created in 2003, after the looting of the Iraqi Museum in Baghdad, to better address the situation in the Near East. Another goal of the IAA is ‘to encourage and promote the study of our disciplines on an international basis’. The association acts as a representative body of Assyriologists in relation to international institutions and the general public and supports the yearly congress ‘Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale’.

When I was elected president of IAA in July 2014, Daesh took the province of Mosul in Iraq. I immediately decided to publish a statement alerting authorities to the perilous situation for cultural heritage objects in Iraq and Syria. Other important activities in my role as president were to coordinate the writing of a guide for an ethical practice of Assyriology, to write supporting letters for endangered institutes, departments, and positions, and to promote young researchers in the field. To enhance our interaction with the general public, we completely restructured the IAA website, adding didactic pages, resources, educational material, links to interviews, videos, and news.

To what extent does your expertise as a historian inform your social engagement?

There are a thousand and one ways to share our work and discoveries with the general public. I have started very modestly by proposing workshops in the schools my three children went to. As they grew up, I proposed more and more complicated activities. Depending on the age of the audience, you have to adapt the stories you tell. As speech alone is not enough, I started to write cuneiform signs on clay and taught colleagues, students, and members of the wider public how to do that. I regularly go to schools in one of the poorest Parisian suburbs and contribute to a national program called ‘Cités Educatives’, where such workshops are very successful. In these schools, the children come from various countries and do not always speak French, but when they have to use a cuneiform syllabary (originally formatted for Semitic languages), they often perform better than French children. When they can express themselves in a language with a common origin, this changes the way children look at each other.

As I was not always able to respond to the increasing number of invitations, I set up a workshop at the Maison d'Initiation et de Sensibilisation aux Sciences on the campus of the Université Paris-Saclay, and trained doctoral students who then run the workshops for schoolchildren. I also made a short educational film on cuneiform script and published online material for teachers who can then conduct the workshop themselves. More recently, together with Vanessa Tubiana-Brun, I produced the documentary 'Thus speaks Taram-Kubi', Assyrian correspondence, which is based on some women’s letters discovered in Kültepe. I take great pleasure in this sharing of knowledge with any audience.

Do you have a favourite written artefact? If so, what is it, and why is it so special to you?

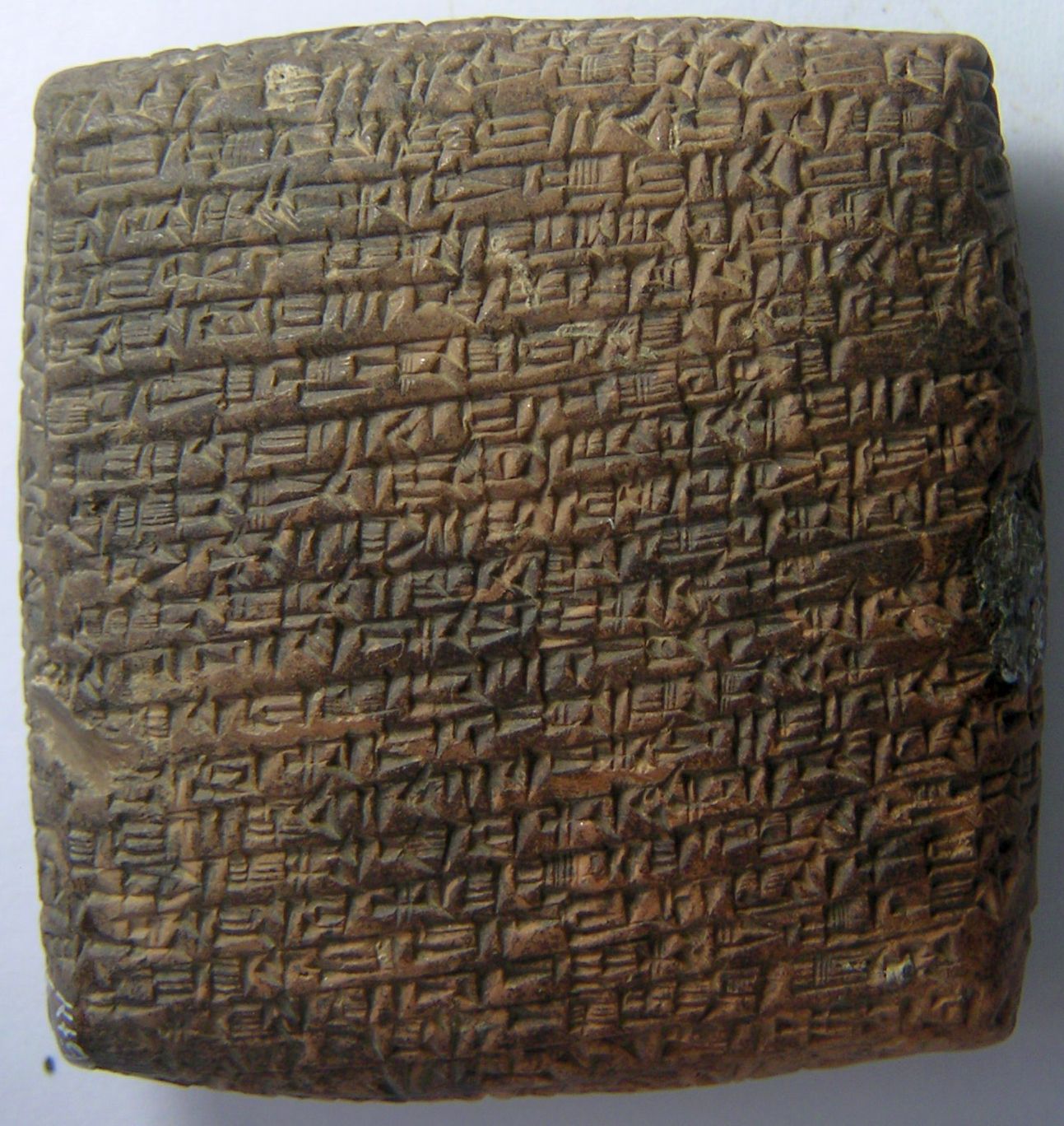

I have many favourite written artefacts and the choice is difficult. The greatest pleasure of an Assyriologist is to work on the original texts, the clay tablets, and to be the first to read them. I am fortunate to be able to regularly work on undeciphered cuneiform tablets in Turkey. I am responsible for the publication of a thousand texts belonging to several members of the same family who lived in a house in the lower city of Kültepe at the beginning of the 19th century BC. If I had to choose only one written artefact, my choice would be the letter that Ummi-Ishhara sent to her sister Shalimma. Ummi-Ishhara is consecrated to the god and therefore unmarried. Shalimma has left her husband and children in Assur to go and live a thousand kilometres away in Anatolia, near her mother. She seems happy there and does not want to return to Assur and to her husband. Ummi-Ishhara tells her about her husband’s depression and how he no longer leaves the house. She gives her a real moral lesson, explaining that a mother does not abandon her children, and finally tells her that if she has left her husband for another man, then she will no longer be her sister. This letter, measuring not more than 5 x 5.5 cm but containing about fifty lines, is a small jewel, combining aesthetics, miniaturisation, and emotional content.

Cécile Michel

is Principal Investigator of two research projects at the Cluster of Excellence: 'Reading Closed Cuneiform Tablets Using High-Resolution Computed Tomography' and 'Archives and Literacy in 2nd Millenium Assyrian Manuscript Culture'. Moreover, she is the head of the Ethics Working Group. From 21 to 25 February 2022, she will teach an introductory-level course on 'Cuneiform Culture and the Akkadian Language 2022' that is open to all.