'Art and Science Shake the Same Tree'Interview with Axel Malik

4 October 2021

The workshop ‘Removed and Rewritten’ concluded with a special event: Axel Malik, currently Artist in Residence at CSMC, presented his ‘Intervention Palimpsests’. In this interview, he talks about the transformative power of writing and the common cause of art and science.

Lesen Sie hier die deutsche Version dieses Interviews

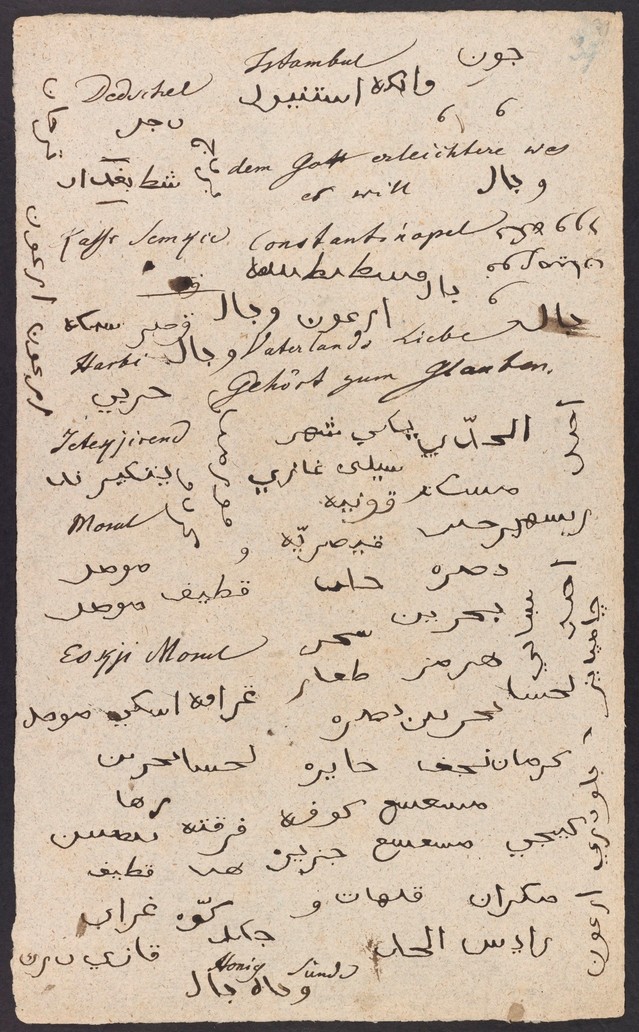

Axel Malik, your ‘Intervention Palimpsests’ deals with some remarkable Goethe manuscripts: his Arabic writing exercises. What are they about?

When Goethe wrote his West-östlicher Divan, he was in a highly sensitive mood towards oriental cultures and all the poetic impulses he could absorb from them. In particular, oriental writings fascinated him, Hebrew, Persian, and especially Arabic. Although he could not read it, he sensed its unique energy, dynamism, and expressiveness. He therefore began to immerse himself in the writing movements of Arabic characters. Without even knowing where one word ends and the next begins, he copied them on paper.

He simply imitated Arabic characters without grasping their meaning?

Yes, he was not interested in learning the language. Nevertheless, he studied oriental scripts intensively over a period of five years. That seems strange, of course: Why would someone like Goethe spend so much time on the seemingly pointless imitation of characters? But in fact he was concerned with more than mechanical copying. There is a reason why he called this activity a ‘spiritual-technical endeavour’ (geistig technische Bemühungen). In Arabic, it seemed to him, spirit, word and script were ‘elementally embodied’ (uranfänglich zusammengekörpert) like nowhere else. He wanted to encompass this cultural space by opening himself to the force of this script. I think this strategy is very intelligent – but also very strange, of course.

What is the connection between this strategy and your own work?

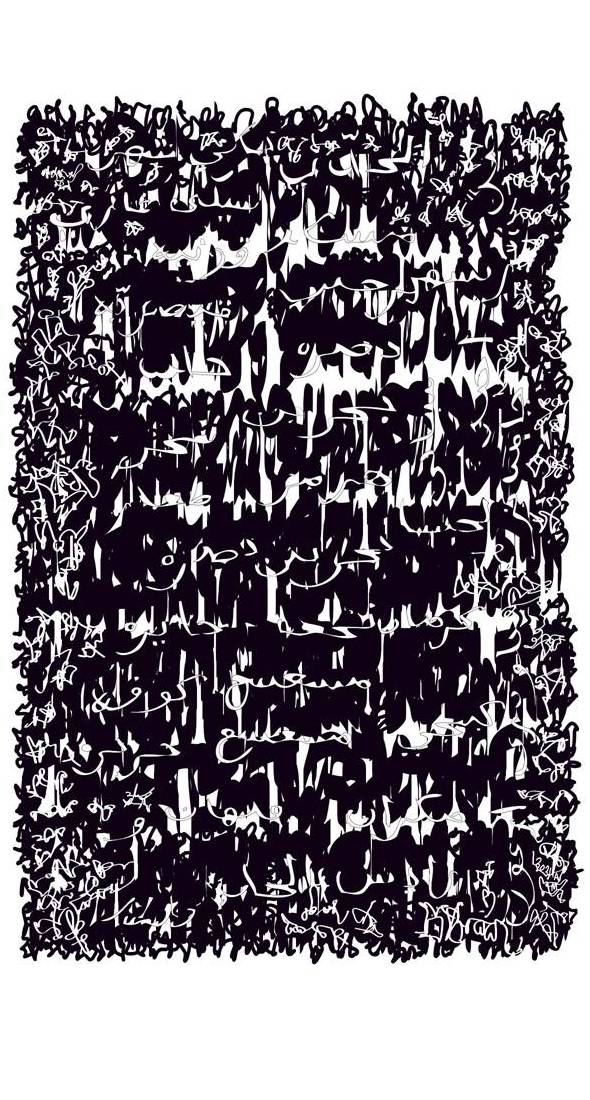

Goethe’s idea of approaching a culture via its script makes perfect sense to me. When you see written Arabic for the first time, you can hardly believe that it is writing. It is hard to imagine how a text can be formatted with all these bows, loops, and dancing rhythms. It is completely foreign and yet – or rather because of this – exerts a strong attraction. How can I make the foreign, which I only see from the outside, resonate in me? That, I think, is the question Goethe asked himself. He approaches everything through the senses. I wanted to respond to this method in an artistic way. This resulted in two large-size works that I will show at the workshop.

The workshop is about palimpsests, that is, manuscripts from which the original text has been removed and which have then been reinscribed. How does your engagement with Goethe’s Arabic writing exercises fit into this context?

The work of Halle O'Neal, who will also be speaking at the workshop, is an important reference point for me. She argues for expanding the concept of palimpsests. According to the common view, palimpsests are products of a situation of scarcity: there wasn’t enough parchment or paper, so the available material was reused. Now, O'Neal has looked at a remarkable Buddhist tradition: when a person died, their relatives would take a sheet of paper with the deceased person’s handwriting and write sacred sutras over it. The religious texts are interwoven and connected with the handwriting, thus establishing a contact with the traces of the deceased.

O'Neal argues for an expansion of the concept of palimpsests because this practice is something quite different from reusing a writing support due to scarcity. Rather, it is part of a ritualised mourning process. It is not about recycling, but about transformation. Absence and presence, appreciation and commemoration are related through writing processes.

Each of my signs is special and raises the question of what a sign is.

The connection to your work on Goethe, then, is the intention to transform the existing handwriting instead of eliminating it.

What seems interesting to me is that when talking about palimpsests, scholars almost always look at the content: What is inscribed in the palimpsests? Can we make the removed text visible again? Besides the content, however, there is another dimension: the writing shape. If I want to say goodbye after the death of a loved one, handwritten traces have a quality that I can engage with. In the same way, Goethe tried to engage physically with the Arabic script to bring to light something that is independent of the content. This is precisely why the artistic contribution is interesting. In my project, which revolves around writing that is illegible, information has no role to play. I do not approach writing through its information content, but through its form. That will be the reference point of my intervention.

What is left of writing when it is not legible, and what can we learn from it?

When you see a written sign, all your thinking about it is based on the premise that it has meaning, that it is defined and can be analysed. I undermine this assumption by preserving certain aspects of what constitutes a sign while removing the essential feature of meaning. Each of my signs is special and thus raises the question of what a sign is. Beyond its informational content, writing always has a body as well. I am only concerned with this body of writing. Focusing exclusively on the writing movement, I produce precise signs each of which is unique. This capacity for differentiation is the subject of my scriptural method.

Your perspective on writing is of course quite different from that of researchers dealing with palimpsests. How do you see this relationship, and what do you expect from the exchange with the other participants of the workshop?

Science aims at generalisability, art aims at individual and unique phenomena. With their very different methods, both find out important things about the world. However, they rarely cross paths. Scientists avoid artists because they do not know how to respond to art in their language, and artists avoid scientists because at a certain point they can no longer understand their arguments. Art and science share few common spaces. Still, we are shaking the same tree, only in different places. If we want to understand what writing is and what it means, we should combine our different impulses.

Axel Malik

is Artist in Residence at CSMC and the creator of the 'Increasing Countdown', which will run on our website until 25 September 2023. His ‘Intervention Palimpsests’ will conclude the workshop ‘Removed and Rewritten: Palimpsests and Related Phenomena from a Cross-Cultural Perspective’ on 7 and 8 October.