Tomography reveals the contents of letters sealed 4,000 years ago

9 October 2024

Thanks to a high-precision instrument that is easy to transport, Assyriologist Cécile Michel has been able to decipher letters enclosed in clay envelopes preserved in Turkey for several millennia.

The ENCI (Extracting Non-destructively Cuneiform Inscriptions) tomographic scanner has just completed its second mission at the Museum of Anatolian Civilisations in Ankara. The first mission took place earlier the year at the Louvre Museum. Thanks to this instrument, the only one of its kind in the world, I was able to decipher letters that had been enclosed in their clay casing for almost 4,000 years.

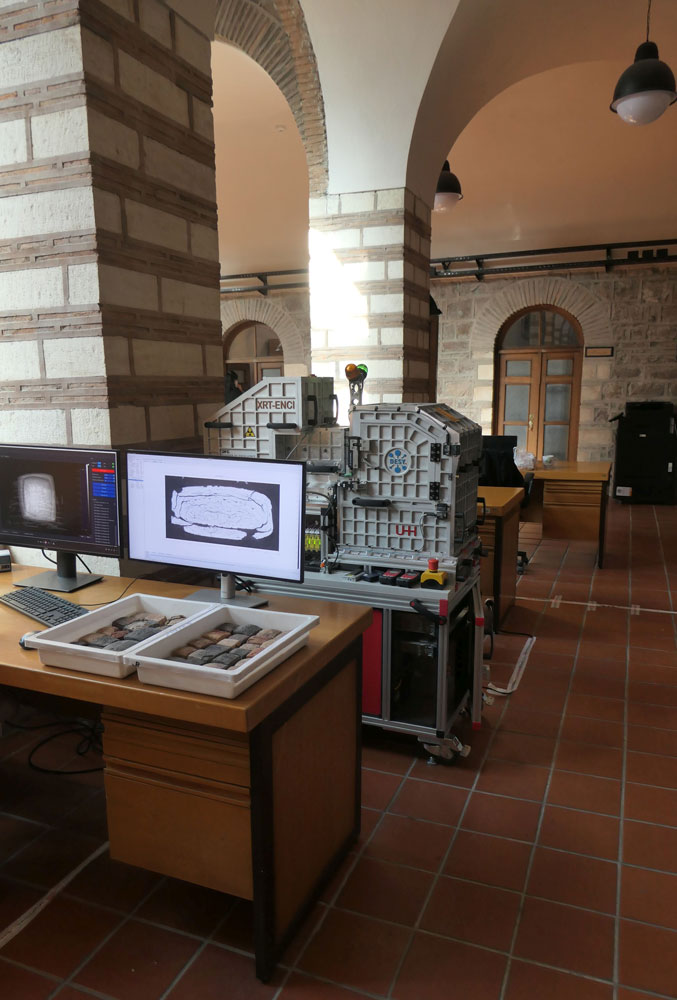

Designed as part of the Excellence Cluster ‘Understanding Written Artefacts’ funded by the German research agency (DFG), ENCI is a very high-definition tomographic scanner whose X-rays can penetrate a brick of clay. It is transportable so that it can be used in museums to scan cuneiform tablets and other very old and fragile objects that cannot be taken out of storage. The instrument can be disassembled into eight parts, which can be stored in the same number of custom-built crates and transported by two to four people. ENCI is powered by a single standard electrical socket, so it can be installed in any space.

Between 15 September and 5 October 2024, ENCI was installed upstairs, in the wide corridor that encircles the courtyard of this former Kurşunlu Han caravanserai built before the 15th century and renovated in the 20th century. While at the Louvre Museum in February 2024 we were able to read cuneiform contracts whose texts were already known because they had been copied onto their envelopes. At the Ankara Museum we mainly scanned letters enclosed in their clay envelopes, with only the names of the sender and recipient(s) legible on the envelope. No one had had access to the contents of these letters since they were put into envelopes in the 19th century BCE!

These letters were discovered in the lower town of Kültepe, ancient Kanesh, not far from Kayseri, in the heart of Anatolia. Assyrian merchants from northern Iraq settled there at the very beginning of the second millennium BCE to conduct long-distance trade. Reading each of these letters from Kanesh provides the historian with new elements for reconstructing the lives of their authors and their economic and daily activities, as well as the political history and events of their country of origin and their country of adoption.

Here are just a few examples of the contents of these revealed letters. Anna-anna wrote to her husband that she had been unable to retrieve the money she had lent to a certain Laqêpum, and that he had replied: ‘I will not give you this money. When your husband comes back, I'll give it to him!’ In another letter, a father and son explained to colleagues that they had taken a sealed IOU from a creditor's archives and given it to the debtor to destroy because he had paid his debt. Another envelope with a bulge on one of its sides actually contained two tablets; as the letter could not be completed on the main tablet, a second, thin oval page, inscribed on one of its sides, had been added.

Access to the cuneiform tablet enclosed in its envelope was possible thanks to the work of an interdisciplinary team. The ENCI parameters had to be calibrated and adjusted to scan the object, then it had to be reconstructed from the 15-micron slices obtained, and finally the surface of the tablet had to be virtually separated from the inside of the envelope to visualise the hidden tablet. Such a project would not have been possible without the collaboration of assyriologists, physicists and computer scientists.

ENCI is preparing to continue its adventures not only in museums but also in the field, because in addition to cuneiform tablets, it has provided high-definition images of Egyptian statuettes, ancient codex bindings, and even thousand-year-old human bones showing pathologies.