At Sîn-nada and Nuttuptum in Ur in 1850 BCE

25 July 2024

Since 2015, archaeologists have been returning to the site of Tell Muqayyar, in southern Iraq, which corresponds to ancient Ur. It was to the south of the city that a German team recently unearthed the house of Sîn-nada and Nuttuptum, providing an insight into the private life of a wealthy couple in this city in the 19th century BCE.

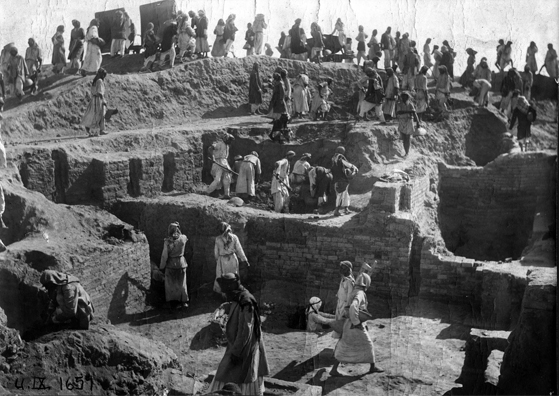

The city of Ur, a port on the Persian Gulf excavated in the aftermath of the First World War by an Anglo-American mission led by Leonard Wolley (1880-1960), was occupied for a very long time, from the 5th millennium to the Hellenistic period. Woolley unearthed the tombs of the kings of Ur dating from the middle of the 3rd millennium, containing material and particularly jewellery made of precious metals and stones. He also uncovered the ruins of the city as it had been at the end of the 3rd millennium, with its wall enclosing the urban quarters and the sacred area dedicated to the Moon God Nanna / Sîn. The wall was destroyed when Ur III fell, and was rebuilt at the beginning of the 2nd millennium by the kings of Larsa.

One of the British archaeologist's most important discoveries was the residential quarters dating from the beginning of the 2nd millennium, at a time when the focus was on monumental architecture. He gave the ancient streets names inspired by those of Oxford, such as Quiet Street and Quality Lane.

Excavations were interrupted before the Second World War, and the site was restored by the Iraqis before being occupied by the American army between 2003 and 2009, causing extensive damage. In 2015, a team of American-Iraqi archaeologists led by Elizabeth Stone and Abdulamir Hamdani resumed excavations at Ur. A small German team led by Adelheid Otto joined them on three campaigns, in 2017, 2019 and 2022. Otto and his team chose to excavate – using all modern techniques – a private house located to the south of the site, close to the enclosure wall (Zone 5).

The archaeologists uncovered a large house built around 1860 BCE, with 16 rooms arranged around a central courtyard and covering an area of 236 m2. The entrance was on the main street, with a garden to the rear. According to the tablets found there, the house was inhabited by Sîn-nada, his wife Nuttuptum and their children, who left toys, rattles and a game board. They were probably a well-to-do couple who were able to build themselves a vast dwelling in this area, which was still largely undeveloped, and lived there until 1835 BCE.

The courtyard opens onto a reception room and main hall to the west, onto a kitchen and pantry where dried meat was kept, and on the east side, opposite the entrance, onto the private apartments. In the latter, the floor was tiled with baked bricks covered with reed mats, and a bathroom fitted with a drainage system added to the luxury of the house. In one of the corners there was an altar with a statuette of a goddess in a niche where the couple could pray, as Sîn-nada had the task of organising the repair of the Ningal temple.

In a corner of the kitchen, under the staircase leading up to the first floor where the family slept, Nuttuptum kept a few treasures: bull's horns, a basket, a small clay plaque representing a god, and letters from her husband telling her that she had nothing to worry about and that he was well. In a small room not far from the kitchen, school tablets were originally kept on shelves. According to Adelheid Otto, during her husband's long absences, Nuttuptum taught her children to read and write. Found in the study, administrative documents for the delivery of grain and brewers' spent grain suggest that Nuttuptum kept a few animals, pigs and sheep, in part of the garden. Alongside the house, the couple had built a tomb containing the bones of deceased family members.

During the latest excavation campaign, archaeologists uncovered a building dating from the end of the 3rd millennium on the lower level, and the results of their work were presented at a conference in July 2024. On the surface of this level, they discovered a tablet with a partial plan of the building and a bowl filled with around ten tablets containing brief notes on the work of masons paid in kind with foodstuffs. There is also mention of a new house and a calculation of the quantities of clay and beams needed to build it. The plan coincides perfectly with part of the house of Sîn-nada and Nuttuptum, built on the foundations of the older building, and is even to scale, which is unusual.

Thanks to the combined efforts of archaeologists, anthropologists, philologists and historians, it is now possible to write micro-histories like that of Sîn-nada and Nuttuptum. This discovery will certainly inspire other researchers working in the region.