A substitute king to deflect divine wrath

23 June 2024

On the evening of the European elections in June 2024, the President of the French Republic decided to dissolve the National Assembly, leaving the country in a state of stupefaction. He could just as easily have resigned, which would no doubt have had a similar effect. In Assyria, the king sometimes chose to disappear, but it was to save his life, and his disappearance was temporary.

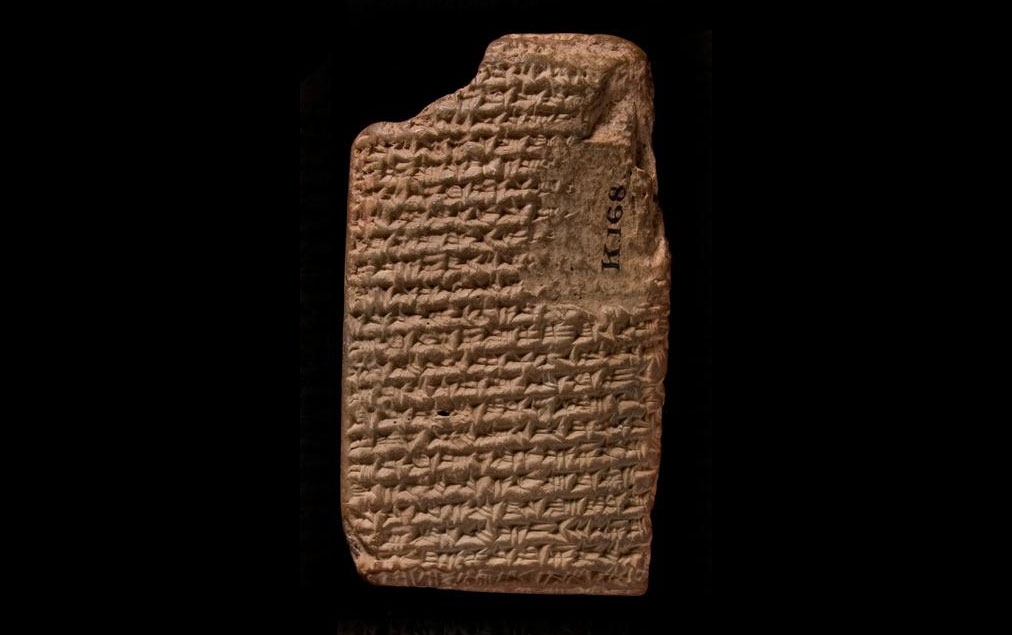

In ancient Mesopotamia, before undertaking any important action, the king had to consult the gods and secure their benevolent agreement, or even their support. The task of the royal astrologers was to analyse the various signs sent by the gods, mainly by observing the movement of the stars in the sky or any other kind of meteorological phenomenon. They had long astrological treatises at their disposal, the most important of which was the canonical series Enûma Anu Enlil (When the gods Anu and Enlil), written on 70 tablets and containing around 7,000 omens based on historical precedents, some dating back to Sargon of Akkad (24th century).

More than half of the tablets in this series concern the movements of the Moon (Sîn) and Sun (Shamash), with a particular focus on eclipses. The temporary occultation of the Sun or Moon was interpreted by astrologers as a metaphor directly affecting the king himself and heralding his imminent demise. Depending on the direction of the shadow, astrologers determined which part of the world was affected. If the northern quarter of the celestial star were to disappear first, it was the king of Assyria who was in danger.

The scholars warned the king when they thought an eclipse was about to occur, so that the ritual of the ‘substitute king’ could be performed to avert the potentially fatal consequences of an omen threatening the sovereign and, by extension, the country. The king would then consult his council of scholars, including astrologers, lamenters and exorcists, on the steps to be taken and the choice of substitute. The substitute had to be insignificant because he was going to lose his life in the place of the sovereign, or else it was an opportunity to get rid of an opponent who was a little too influential.

The substitute king then took on the insignia of royalty, but without exercising power, while the sovereign took his place. Assarhaddon was thus called ‘farmer’. Once the danger had passed, the substitute king who had taken on the divine sentence would die, and the true sovereign would resume his place on the throne.

The practice of the substitute king is an ancient one, dating back to at least the very beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE. It was however fully recorded in cuneiform texts only from the time of the Assyrian Empire (911-612 BC), particularly during the reigns of Assarhaddon (680-669) and Assurbanipal (668-627), a period in which no fewer than ten substitute kings briefly wore the crown.

A letter sent to Assurbanipal by one of his agents in Babylonia describes the funeral of a certain Damqî, son of an important religious dignitary from Akkad, who served as substitute king at the end of 671 BCE. Presumably chosen because of the power exercised by his father, he and his wife ascended the throne of Babylon as a substitute for Shamash-shum-ukin, the brother of Assurbanipal, who was then ruling in Babylonia. After taking on the wrath of the gods threatening Shamash-shum-ukin and his queen, Damqî and his wife were given a royal funeral to complete the ritual: they were decorated, treated, displayed, buried and mourned. The burnt offering was made, all omens were cancelled, and numerous apotropaic rituals, adapted ceremonies, exorcist rites, penitential psalms and ominous litanies were performed to perfection.

The French President has a choice substitute in the person of the Prime Minister. Even if the Prime Minister does not temporarily occupy the presidential seat, he serves as a fuse for the Head of State.