The oldest peace treaties

13 January 2024

Although wars and conflicts date back to the origins of humanity, the oldest peace treaties date back to the 3rd millennium BCE. Assyriologist Cécile Michel invites us to discover these cuneiform texts in this new post on the blog Brèves Mésopotamiennes.

The year 2023 was marked by wars that continue to plunge the world into mourning. Conflicts and wars go back to the origins of humanity, and a happy conclusion can be reached in a peace agreement, possibly ratified in writing. Cuneiform texts dating from the 3rd millennium BCE represent the oldest known peace treaties.

In southern Mesopotamia, in Uruk, a new dynasty was established from the middle of the 3rd millennium. Enshakushana, believed to be the descendant of a king of Ur and to have defeated the king of Kish, was the first to bear the title "King of Sumer". His successor, Lugal-kinishe-dudu, is said to have concluded a treaty of brotherhood with Enmetena, who reigned over the kingdom of Lagash in around 2420 BCE. A foundation nail discovered in several copies commemorates the construction of a temple at Bad-Tibira by the latter and states: "at that time, Enmetena, king of Lagash, and Lugal-kinishe-dudu, king of Uruk, established a mutual pact of brotherhood".

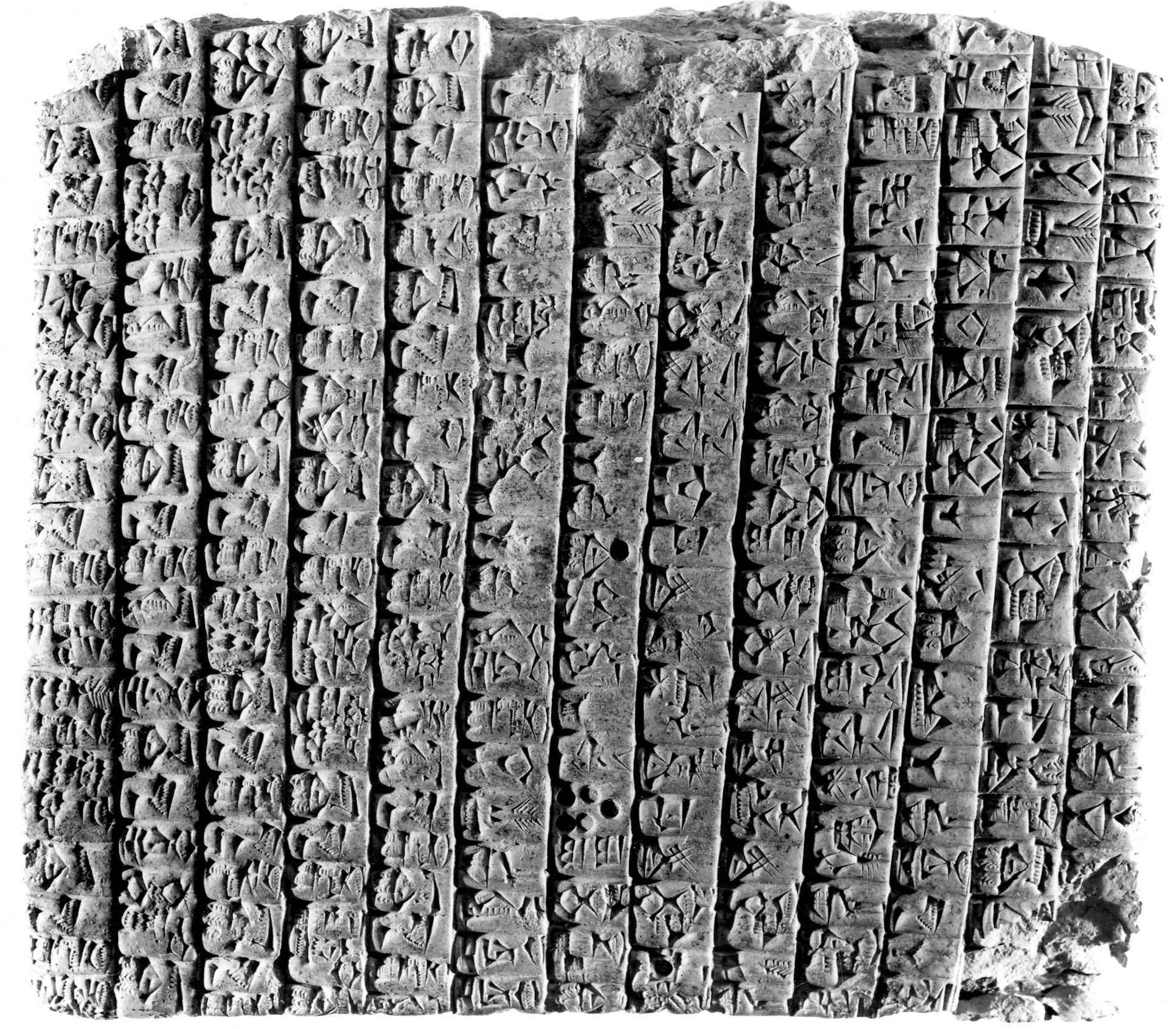

The oldest known diplomatic treaty celebrating peace between two states was concluded between the kings of Ebla and Abarsal in around 2350 BCE. Discovered at Ebla, 65km south of Aleppo in Syria, and written in the Eblaite language, it sets out Abarsal's new status as a vassal of Ebla following its defeat. Abarsal was a lesser town on the opposite bank of the Euphrates, between Upper Habur and Balih. The 40 or so clauses include an adjustment of the border between the two kingdoms, agreements on the exchange of goods, the movement of travellers by land and river, and their reception in the neighbouring country.

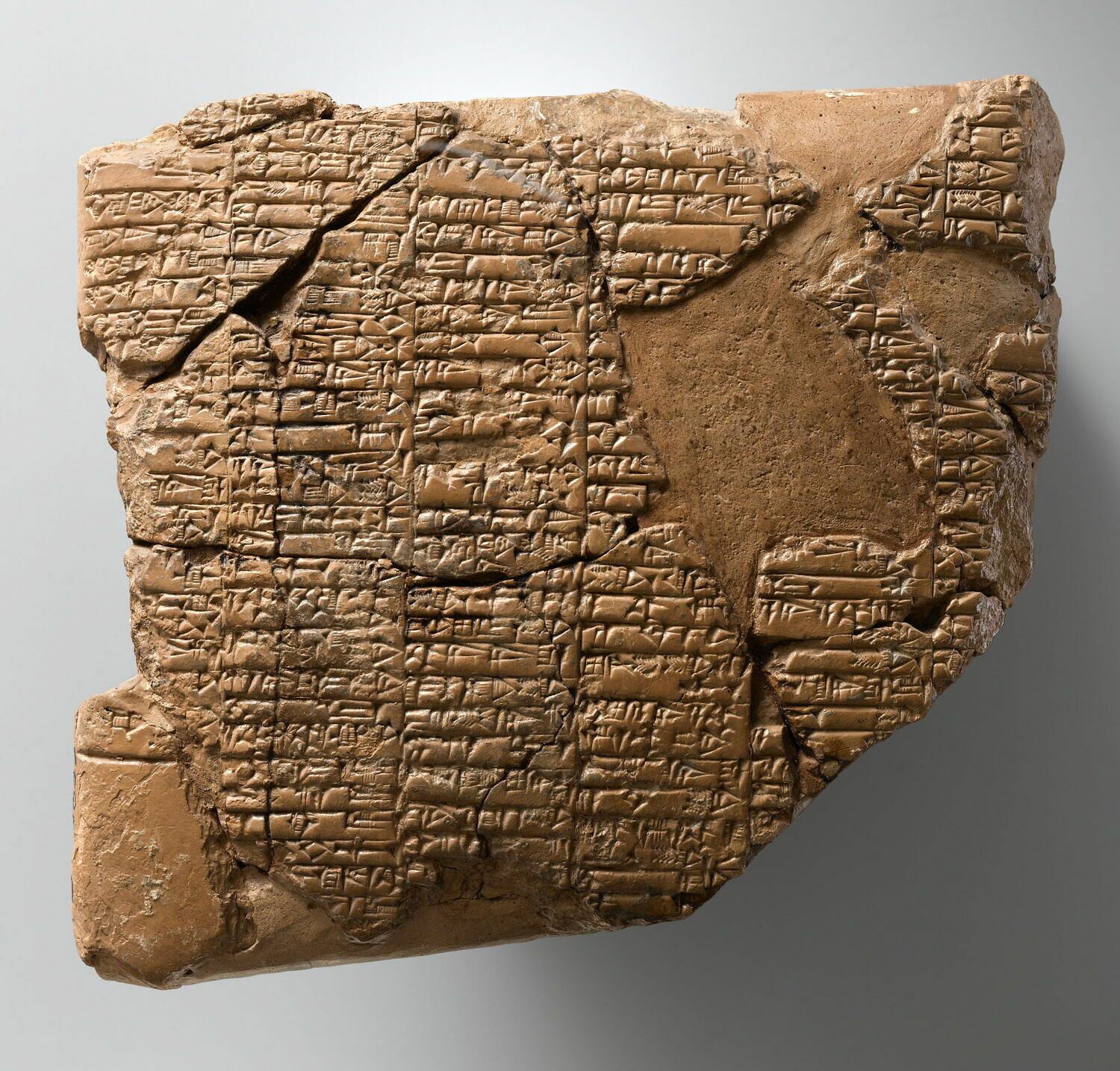

Another treaty, written in the Elamite language, was discovered in Susa (Iran) and signed in around 2250 BCE between Naram-Sin, king of Akkad (in the Baghdad region), and a ruler of Awan (Elam). It consists of a long oath sworn by the king of Elam, promising loyalty and military support for the king of Akkad against his enemies: "The enemy of Naram-Sîn is my enemy, the friend of Naram-Sîn is my friend".

These international agreements – with the exception of the allusion to the brotherhood agreement between the kings of Uruk and Lagash – were not parity agreements because the clauses were not reciprocal. They were treaties of vassalage, of which only one version has survived. The kings of Abarsal and Akkad must also have kept their own version in their palace archives, written in the language of their country. There were many more peace treaties, both joint and otherwise, in the second millennium. The most famous of the 35 agreements recorded commemorate the peace signed between Zimrî-Lîm of Mari and Hammurabi of Babylon (around 1770 BCE) and that concluded between Hattushili III, king of the Hittites, and the Egyptian Ramses II (1260 BCE). The Egyptian version of the latter treaty is also engraved in stone in hieroglyphs at Karnak, and at the Ramesseum in Thebes. Finally, a dozen treatises using cuneiform syllabics have been unearthed in the ruins of Assyrian palaces (800-612 BCE).

Like these ancient rulers, it is time for today's political leaders to become wiser and to declare peace. As Jean-Paul Sartre wrote in his play The Devil and the Good Lord (1951): "When the rich go to war, it's the poor who die”.