A personal seal to authenticate and protect one’s assets

29 November 2023

A seal is an object on which figures are engraved in negative, and whose imprint is affixed to documents or objects to authenticate and seal them inviolably. Seals have existed since ancient times, and in Mesopotamia they were applied to fresh clay to leave their imprint.

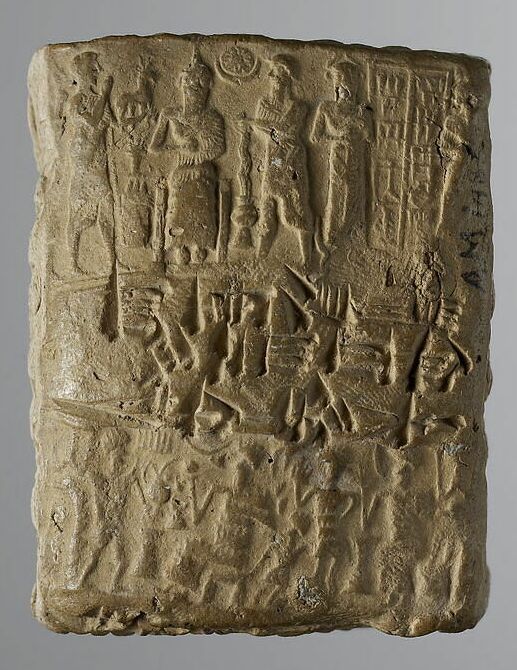

Clay is a malleable plastic material, which easily takes the imprint of whatever is intentionally or unintentionally applied to it. In the ancient Near and Middle East, clay was used for a wide variety of purposes, including being shaped into tablets for writing on, or used as a seal to close doors, chests, baskets, textile or leather bags and other containers. A seal was regularly affixed to clay tablets, envelopes and seals.

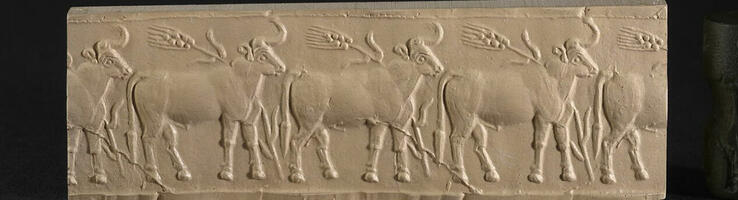

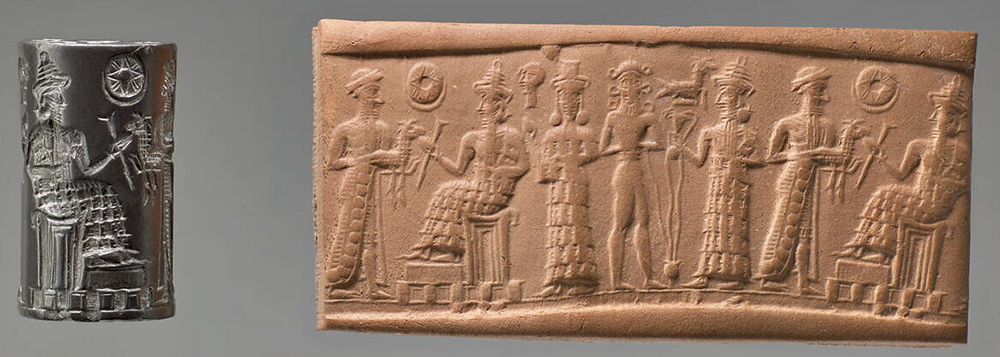

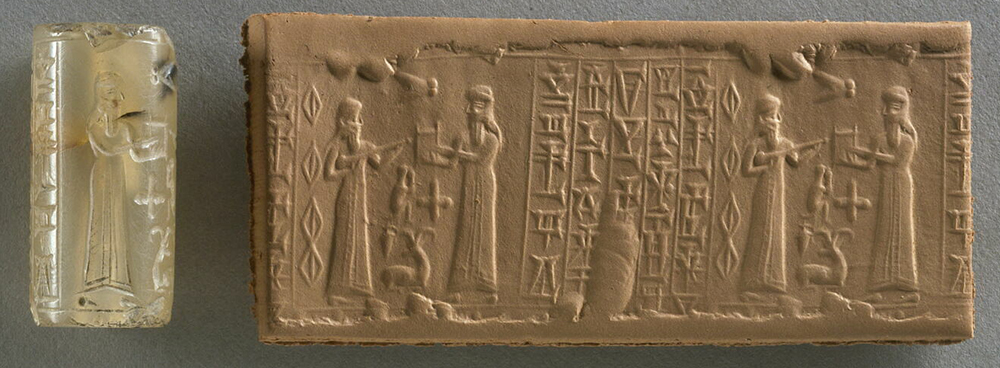

Seals appeared in this region as early as the 7th millennium BCE, well before writing. They were applied to pieces of clay to seal goods. The cylinder seal came into use at the very end of the 5th millennium. It was rolled out onto a clay surface, leaving a positive imprint. The small cylinder, usually carved from stone, was thick at first but became thinner over the centuries, and was pierced by a hole lengthwise. Made of semi-precious stones such as hematite, lapis lazuli and rock crystal, seals were valuable personal possessions. Many of them are catalogued by the impressions they left on envelopes, tablets and seals.

Cylinder seals feature a wide variety of miniature scenes, depending on the period, region and context. There are many different styles and motifs, some of which depend on the choice of the seal's owner and his or her professional activities. The most predominant scenes are religious, such as a presentation to a deity, figures at prayer, or a libation. Next come mythological scenes illustrating epics and legends, with, for example, battles between heroes, monsters or animals. Royal scenes show the sovereign grappling with an enemy, hunting a wild animal, or taking part in a banquet, complete with music and dance. Finally, other seals illustrate scenes from everyday life, such as textile work, spinning and weaving, or the practice of certain trades such as that of the butcher, or the breast-feeding nurse.

Some seals had a legend engraved on them, usually consisting of just two or three lines. These included the name of the seal's owner and that of his father and possibly of his personal god. Rarer were the seals that had only text, a kind of prayer transforming the object into an amulet with magical power.

The seal was a personal object, often worn as a pendant or attached to clothing with a string or chain. When the seal had no inscription, the members of the community could identify its owner from the scene depicted: "We have entered the house and we have identified the seal whose imprints appear on the seal attached to the cloth: they are really the imprints of the seal of Imdî-ilum". Most seals are identified by their impressions.

All kinds of goods could be sealed by their owner: a house, a room or various containers. All they had to do was affix a clay strip to a latch or to the knots closing a bag and affix their seal. At the beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE, letters were sent enclosed in a thin layer of clay. This envelope had a dual purpose: to hide the text of the letter and to protect the tablet during transport. The name of the addressee was written on the envelope, sometimes with that of the sender, and the latter's seal was unrolled on the front, back and all edges of the envelope, by way of authentication.

In the case of contracts, the documents – tablet or envelope – were sealed by at least one of the parties and the witnesses who had witnessed the deed. In the case of a loan, the debtor sealed the acknowledgement of debt entrusted to the creditor, who could then display the document at any time to prove the loan he had made. In the case of a purchase, it was the seller who affixed his seal to the contract to certify that he had received the sale price of the property. Those who did not have a seal, no doubt because they were too poor to have one engraved, could seal a document using another object that was a substitute for their person, such as a fringe of their garment or the ring on their finger, or they could simply repeatedly dig their fingernail into the clay.

Breaking a person's seal was a formal act that could only be performed in the presence of witnesses and with special authorisation. Thus, in the nineteenth century, the authorities of an Assyrian trading post gave the following orders: "Break the previous seals, take note of the tablets, and the seals that you have broken, place them inside the tablet containers. Seal them (all) and give them under your seal to Mada, our messenger, so that he may bring them to us".

Mesopotamian cylinder seals are still highly prized objects today, not only because of the preciousness of their material, but also for the finesse and beauty of the miniature scenes engraved on them. In the 1870s, the archaeologist Henry Austen Layard had a necklace of Mesopotamian cylinder seals made for his wife. There are many seals in collections and museums around the world, but they are also the objects most sought-after by antiquities traffickers, because their small size makes them easy to conceal. For example, several thousand cylinder seals kept at the Iraq Museum in Baghdad have never been found since they were stolen in 2003.