Discovery in Anatolia of a new language written in cuneiform

27 October 2023

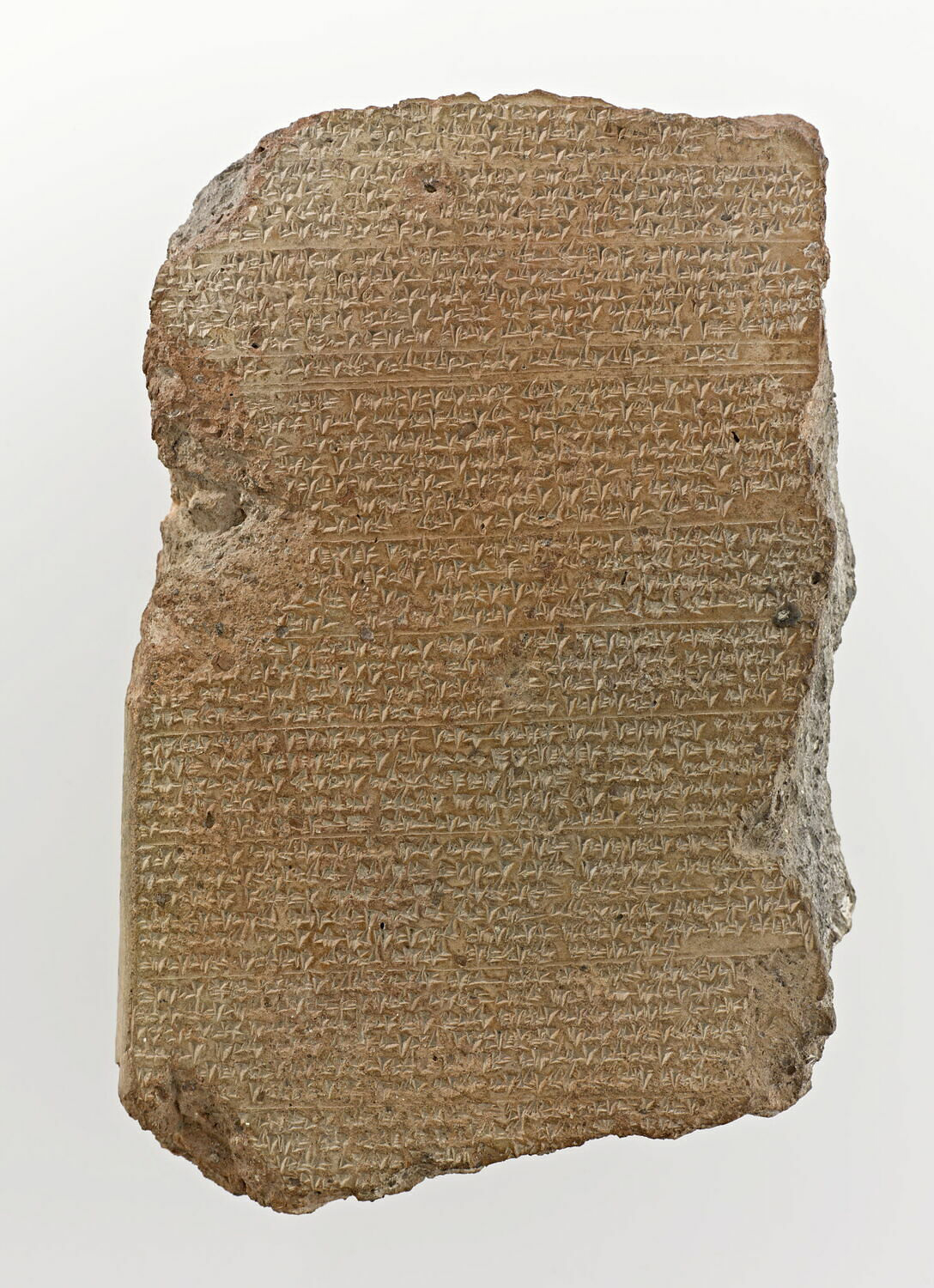

Cuneiform writing, invented by the Sumerians in the second half of the fourth millennium BCE, was used to record a dozen different languages. The archaeological team excavating the site of Boğazköy in Central Anatolia, the ancient Hattusha capital of the Hittites, has just unearthed a cuneiform tablet with text in a hitherto unknown language.

The cuneiform script developed by the Sumerians to write their language – an isolated language – was originally logographic, i.e. one sign for one word. Cuneiform signs were made up of a variable number of "nails" printed into fresh clay using a stylus. In the middle of the third millennium, this writing system was adopted by the Akkadians, a Semitic population that settled between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Iraq. They used the sound of signs to write their language using syllabic signs. In central Syria, the inhabitants of Ebla also adopted syllabic cuneiform writing for their Semitic language, Eblaite.

At the end of the third millennium and during the second millennium, other populations in Mesopotamia used the syllabic cuneiform system to write down their language, whether Semitic, such as Amorrite, or isolated, such as Kassite spoken by the inhabitants of Zagros, the Hourite language spoken in northern Mesopotamia and south-eastern Turkey, and Urartean spoken in the Lake Van region. In Iran, cuneiform texts are written in Elamite, another language not related to any known linguistic family. There are also two cuneiform alphabets, the first used to record Ugaritic in Ugarit, a West Semitic language, in the 14th-13th centuries, and the second used for Old Persian in Iran, between the 6th and 4th centuries.

In the third millennium, the inhabitants of Central Anatolia spoke Hatti, an isolated language. The people who settled in the region in the second millennium, on the other hand, communicated in Indo-European languages, a language family to which French belongs. The first evidence of Hittite words can be found in the tablets of the Assyrian merchants who settled in Kültepe, the ancient Kaneš, not far from Kayseri, in the 19th century.

The Hittites, who ruled Central Anatolia between the 17th and early 12th centuries, adapted cuneiform writing to their language, using sumerograms (a sign for a word) and akkadograms (a combination of syllabic signs forming Akkadian words) and syllabic signs to write their language phonetically. Some Hittite texts include passages in Palaito, another Indo-European language for which fragmentary religious texts have been discovered. There are also glosses or magico-religious phrases in Louvite. From the 15th century onwards, however, Luvite was used to write hieroglyphics and monumental inscriptions.

It was at Hattusha, in the Yozgat region, a UNESCO World Heritage site where almost 30,000 cuneiform tablets have been discovered over the last century, that the archaeological mission led by Andreas Schachner unearthed a ritual text in Hittite last month, including an extract written in a language previously unknown. The language is described as that of the land of Kalasma, already attested in the annals of Mursili II (c. 1321-1295), which is located to the north of Ankara. This language, which is also Indo-European, is thought to share some characteristics with Louvite. The possible existence of this idiom was suggested by a German scholar in the late 1950s. He noted that the officials of Kalasma took their oaths in a dialect that differed from that of other Hittite regions.

The texts unearthed at Hattusha are historical, administrative, legal, academic and religious in content. The numerous religious texts include myths, hymns and prayers, descriptions of festivals and cults celebrated for the deities, as well as magico-religious texts. The latter regularly record, in the original language, rituals from various Anatolian, Syrian and Mesopotamian traditions, demonstrating the interest shown by royal scribes in these different cultures.

Other texts written in this idiom will be needed before this new Kalasmaite language can be deciphered. Language is one of the key elements in the cultural identity of peoples, and it is through language that we can understand cultural diversity.