How did the ancient Mesopotamians archive their cuneiform tablets?

13 September 2023

In the digital age, our archives are increasingly compact and ephemeral: we have partly replaced paper with files on the computer, organised in folders, which we sometimes keep backed up on external hard drives. Paper documents and letters are nevertheless still part of our environment.

We archive and file them in labelled cardboard folders and files. But how did the ancient Mesopotamians store their clay tablets, which were much larger than a single sheet of paper?

We archive and file them in labelled cardboard folders and files. But how did the ancient Mesopotamians store their clay tablets, which were much larger than a single sheet of paper?

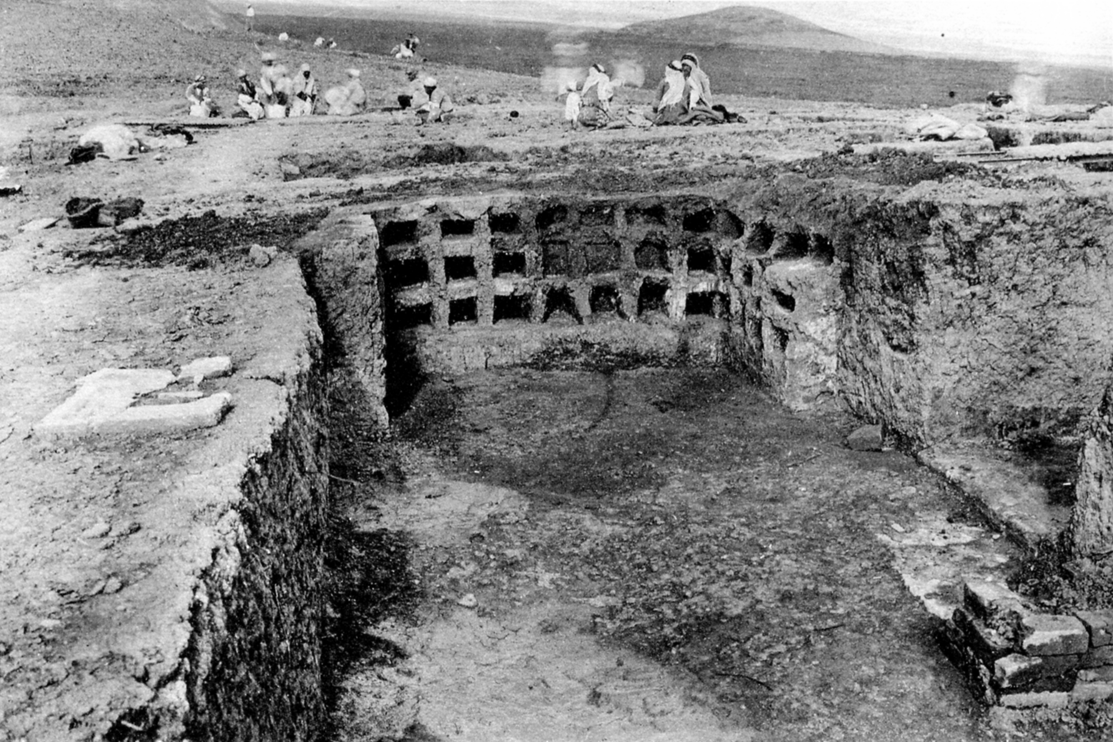

Mesopotamia was a civilisation of the written word, and the hundreds of thousands of cuneiform texts unearthed at sites in Iraq, Syria, Iran and Turkey took many different forms and covered a wide range of subjects. Scholarly texts – e.g. literary narratives, poems, proverbs, hymns, and mythological, medical, mathematical and encyclopaedic texts – formed libraries in temples, palaces and the homes of priests and scholars. The tablets were often stored in niches in walls built of unbaked clay bricks.

Certain inscribed objects, such as royal inscriptions, statues and stelae, or votive texts, were placed in strategic locations; some, to be read by humans, were displayed prominently in institutional buildings, while others, destined for the gods and future kings, were buried in the foundations of these buildings.

The archives of the palaces and temples included thousands of administrative and accounting texts showing the management of resources by these great institutions, as well as treaties, diplomatic correspondence, letters received by the king, members of his family and his court, descriptions of rituals, school texts, etc. In a room in the palace of Ebla, Italian archaeologists discovered more than 17,000 clay tablets and fragments forming the archives of the kings of Ebla in the 25th and 24th centuries BCE, including numerous expenditure and revenue registers and stock inventories. The wooden shelves, which were often large and square, were arranged according to their contents along the walls, and some fell to the floor as the wood decomposed.

In the palace of Mari, on the Middle Euphrates in Syria, the archives, which were about as numerous and dated back to the 18th century BCE, were divided into different sectors according to their content. Most of them date from the reign of Zimrî-Lîm, the last king of Mari (1775-1761 BCE). Correspondence was kept in the area inhabited by the women, while tablets listing the foodstuffs brought out daily from the palace storerooms to prepare meals for the king and his court were discovered not far from the kitchens. Other administrative tablets were unearthed near the storerooms. When Hammurabi's Babylonian troops took Mari in 1761, the Babylonian scribes opened all the baskets containing the tablets and sorted them out. They removed the diplomatic correspondence between the sovereigns of the main kingdoms, including Babylon, and left behind all the administrative documents. These they placed in baskets which they sealed with a new clay label specifying the contents: "tablets of the servants of Samsî-Addu" or "tablets of the servants of Zimrî-Lîm". The French archaeologists who have been excavating the site since 1933 have thus discovered not the original classification of the archives, but a secondary classification carried out by the victorious Babylonians.

Private individuals, for their part, kept dozens, hundreds and sometimes even more than a thousand cuneiform tablets in one or more rooms of their homes, making up their private archives. These were family or commercial contracts, including IOUs and contracts for the purchase of houses, fields and slaves, as well as various legal documents and memoranda. These tablets were stored in cloth bags, wooden crates, reed baskets or clay jars – all organic materials that have disappeared over time, leaving only the jars.

In the house of Ur-utu (17th century BCE) unearthed in ancient Sippar, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in southern Mesopotamia, 207 of the 2,500 tablets unearthed were stacked in four perfectly aligned layers. They must originally have been kept in a quadrangular box made of wood or reed, the dimensions of which have been reconstructed. The bottom layer consisted of old family documents, and on top were documents added when the archives were reorganised.

Clay labels attached to baskets, jars and crates indicated their contents. Among the Assyrian merchants who settled in Central Anatolia, in ancient Kanesh, archives were generally organised by type of document (letters, documents of legal value), by file or, in the case of letters, by sender. Today, many archaeological sites in the Near and Middle East have been looted, and the context of many tablets originally kept in private homes has been lost forever; we no longer have any information about their original organisation.

The written material we produce today is increasingly ephemeral. Since the end of the 20th century, some countries have been looking for solutions to preserve their written cultural heritage, mainly books. In Germany, the microfilm format has been chosen since 1975, and almost 32,000 km of microfilms stored in sealed steel drums are preserved in the Barbarastollen underground vaults. In Austria, the Memory of Mankind Foundation has chosen clay as its medium since 2012, echoing the cuneiform tablets, some of which have survived for more than 5,000 years. On a ceramic microfilm tablet, it is possible to store a book of a thousand pages in analogue form. These tablets are buried at a depth of 2,000 metres in the oldest salt mine in the world, at Hallstatt, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Pictographic indications should enable future discoverers of these tablets to decipher them. In both cases, the aim is to preserve books, but the private archives that make it possible to reconstruct personal histories are doomed to disappear.