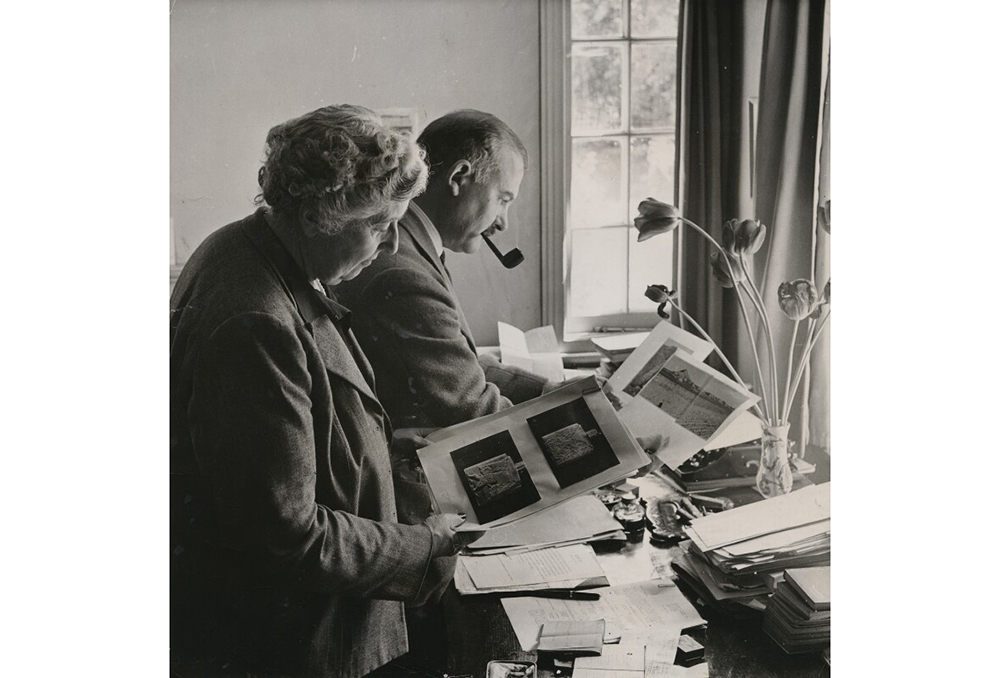

Agatha Christie, a novelist on the digs

22 January 2023

In the 1930s, Agatha Christie accompanied her husband to several archaeological sites in Iraq and Syria. These trips were to inspire the novelist, as Assyriologist Cécile Michel recounts in this post on her blog Brèves Mésopotamiennes, now available on CNRS le Journal.

In 1930, Agatha Christie accepted an invitation from Leonard and Katherine Woolley to visit the site of Ur, in southern Iraq. Little did she know that her life was about to change radically. She was entrusted to a young assistant, Max Mallowan, who showed her around the region. Despite their age difference – she was fourteen years older than him and had been divorced for two years – and their religious differences – he was Catholic and she Anglican – they married on 11 September 1930.

Agatha accompanied her husband into the field, initially in Iraq, then under British mandate. In 1933, Max Mallowan took charge of excavations at the small prehistoric site of Tell Arpachiyah, near Mosul in northern Iraq, a site discovered in the late 1920s by R. Campbell Thompson. Dated to the Halaf and Obeid periods, it was an important site for the production of ceramics and the obsidian trade. A major political crisis in Iraq drove the archaeologist away and he went to work in Syria, which was under French mandate at the time.

From 1934 onwards, Agatha Christie began a diary in which she vividly recounted five seasons in Syria and daily life on the excavation sites. This diary was published in 1946 under the title Come, Tell Me How You Live, translated into French as La romancière et l'archéologue. Mes aventures au Moyen-Orient(2005). The story begins with a trip on the Orient-Express, followed by prospecting in Syria to find the tell on which Max intended to conduct his research. He hesitated between three sites in the north-west of the country, and finally chose Tell Chagar-Bazar, occupied from the Halaf period at the end of the Neolithic, until the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE.

In the course of three campaigns between 1935 and 1937, he established the stratigraphy of the site and uncovered buildings dating from the early 2nd millennium, in which he discovered 124 cuneiform tablets. These tablets, along with the other remains unearthed on the site, were shared between Syria, for the Aleppo Museum founded in 1931, and England, for the British Museum. Agatha Christie explained how the antiquities were divided up:

The crucial moment, the "division", is almost upon us. At the end of each season, the Director of the Antiquities Service comes in person, or delegates someone to divide the objects found on the excavation fields into two batches. In Iraq, he would go through each piece one by one, and this would take several days. In Syria, the working method is much simpler. Max is left to divide the objects into two batches of equal value. He can do as he pleases. Then the Syrian representative arrives, examines everything and chooses the collection he prefers to keep. The other is packed up and sent to the British Museum. (p. 209)

In the late 1990s, more tablets were unearthed during further excavations at Chagar Bazar, thus making it possible to identify the site with ancient Ašnakkum. The finds now remain in Syria.

In 1936 Max Mallowan decided to explore Tell Brak in the valley of the Jaghjagh River, one of the tributaries of the Habur. Known under the ancient name of Nagar, this was a vast site covering several tells and occupied from the 7th millennium to the end of the 2nd millennium BCE. There he discovered a temple dating from the end of the 4th millennium, in which he found hundreds of small statuettes with oversized eyes that he called "eye idols" or "idols with glasses". Agatha Christie took part in the excavation campaigns, recording, photographing and restoring the objects discovered. The digs at Tell Brak were stopped in 1939 with the outbreak of the Second World War.

Her travels in Syria and Iraq, and life on excavation sites, inspired Agatha Christie to write two detective novels in which Hercule Poirot leads the investigation. In 1934 she published Murder on the Orient Express, based on a true story, and in 1936 Murder in Mesopotamia, set at the imaginary archaeological site of Tell Yarimjah, not far from the Tigris River in Iraq. In this small, closed world, she caricatured some of the members of the missions she had worked with, and had the wife of the excavation director murdered – a literary act of revenge against Katherine Woolley, who had refused to allow her to accompany Max to Ur after their wedding. In a third novel, They Came to Bagdad, published in 1951, a young woman sets off to Baghdad in pursuit of her lover, where she meets two archaeologists.