Reading and writing, a matter for men... and women in Mesopotamia

29 October 2022

The history of ancient Mesopotamia is based on more than a million cuneiform texts unearthed to date. Until the end of the 20th century CE, this history was above all one of men, based on ancient texts mainly written by men. However, Assyriologists have a significant number of direct sources written by women, making it possible to clarify their place in Mesopotamian society.

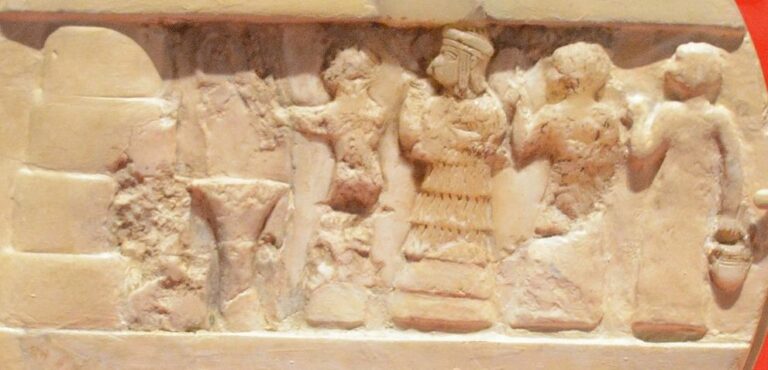

The earliest known female author in human history is the priestess Enheduanna, daughter of King Sargon of Akkad, who lived in Ur in the 23rd century BCE. This woman dedicated to the moon god Sîn left hymns to the goddess Inanna as well as hymns to temples known from copies of the late third millennium. Some scholars do nevertheless wonder whether she wrote these hymns herself or whether someone else wrote them for her.

Enheduanna's disc.

Enheduanna's disc.This is probably due to the fact that almost all the scribes mentioned in the texts were men. However, not only were female scribes mentioned, but also, depending on the context and the time, some women were clearly able to read and write, as were some men. Women scribes were best represented in settings where there were few men. At the beginning of the second millennium BCE this was the case, for example, of the female population of the palaces and of the communities of consecrated women.

Over five hundred women lived in the palace of Mari (Middle Euphrates, Syria) during the reign of King Zimrī-Lîm (1775-1761 BCE). In addition to the women of the royal family, many slaves were in charge of maintenance and supplies, and they included nine women scribes. Three of them wrote hundreds of tablets recording the daily output of food from the palace shops for the king's meals.

In Sippar (central Iraq), young girls from wealthy families were dedicated to the sun god Shamash. They were forbidden to marry and to give birth to children. At the time of their consecration they received a dowry including land which they managed as they wished. They used the written word to buy, sell or rent their land and to correspond with their families. To do this, some employed women scribes, consecrated or not, who drew up contracts often involving men and women. Other nuns wrote their own tablets.

Women scribes received the same education as men. Some school texts signed by apprentice scribes show that they could reach an advanced level of study by copying literary texts in Sumerian.

In other places and environments, boys and girls could learn the basics of reading and writing at home, from a parent or other family member, which allowed them to write accounting records, memoranda, and correspondence. This was probably the case for some merchant families in Ashur in the 19th century BCE. Letters sent from this city have been discovered in Kültepe, the ancient Kanesh in the heart of Anatolia, chosen as a central trading post by the Assyrians.

The 23,000 cuneiform tablets found in the lower city have been widely exploited for their rich data on trade and markets with important financial innovations, and the activities and lives of several male merchants have been studied in detail. Some Assyrian women, resident in Ashur and known from the letters they sent to Kanesh, are particularly visible in these clay manuscripts. Remaining for many months alone in the city-state, managing their household and producing cloth for the international trade, they were the authors of several hundred letters about both financial and domestic matters. These women used writing as a means of communication and their letters show a certain expression of feelings. As evidenced by accounting documents and palaeographic studies of some tablets, some of these women wrote their letters themselves.

These data, although fragmentary and linked to specific social groups, allow us to complete our knowledge of the role played by women in Mesopotamian society and to compare it with that of men. Thanks to these cuneiform tablets, it is possible to hear the voice of those ancient women who were educated and enjoyed some degree of autonomy.