New discoveries on the first writings in Anatolia

26 September 2022

While two distinct forms of writing developed in the second half of the 4th millennium BCE in Mesopotamia and Egypt, there is no record of writing in Anatolia before the very beginning of the 2nd millennium. Cuneiform writing was taken by Assyrian traders to Central Anatolia and was used to transcribe their language.

The 23,000 cuneiform tablets discovered in Kültepe, the ancient Kanesh (not far from the modern city of Kayseri), are written in the language of the Assyrians, as are the 150-200 tablets unearthed in Alishar, the ancient Amkuwa, and Boğazköy, the ancient Hattush(a), all dated to the 19th and 18th centuries BCE. Some local merchants borrowed Assyrian writing and language; their archives, consisting of one or more dozen tablets, were found in their houses in the lower city of Kanesh. The rare diplomatic letters exchanged between Anatolian rulers from this period were also written in Assyrian using the cuneiform syllabary.

One wonders why the Anatolians simply adopted the Assyrian script and language for their own purposes and did not attempt to adapt the cuneiform script to their own language as the Hittites did from the late 17th century BCE onwards, and whose history can be reconstructed from these texts. Some researchers have suggested that a form of local writing already existed at the beginning of the 2nd millennium. Signs visible on seal impressions and graffiti found on three vases discovered at Kültepe are thought to represent an archaic form of the Anatolian hieroglyphs known to have been used from the last quarter of the 15th century to transcribe the Luvian language.

This hypothesis is not without its problems. If the rare signs discovered at Kanesh prefigured the hieroglyphs used three centuries later, would there be a form of writing sufficiently developed at the very beginning of the 2nd millennium to allow the writing of complex accounting documents mentioned in the cuneiform texts? How is it that there is no trace of it? And how can we explain that the Anatolians used cuneiform writing and the Assyrian language for their own purposes and not these hieroglyphs? While the Assyrians were settled in the lower city of Kanesh, the Anatolian populations do not seem to have used their own writing that allowed for complex expression.

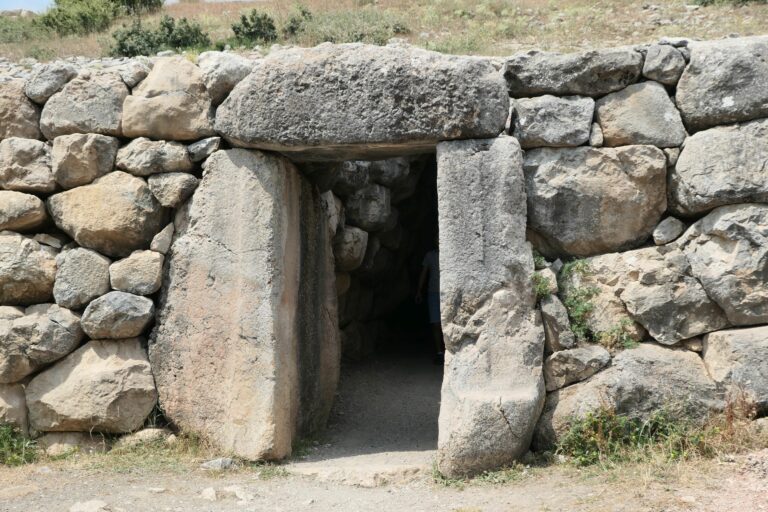

The hieroglyphic Levite inscriptions discovered previously were on seals or large rock monuments. Then, in the summer of 2022, Andreas Schachner's team excavating in Boğazköy, the ancient Hattusha, capital of the Hittites about 200 kilometres east of Ankara, discovered 249 brown-red signs on the stones of the Yerkapı postern. The signs, which are scattered on the blocks of the 80-metre-long underground tunnel, were painted with a vegetable dye, probably around the end of the 15th century BCE.

A digital survey of these hieroglyphs is currently underway. According to initial observations, they are not a long narrative inscription but rather graffiti, with eight different groups of signs repeated many times. According to the director of the excavation, the history of the Hittites is mainly known from cuneiform texts written in the Hittite language. But there was a writing system specific to Anatolia, which survived for more than 400 years after the fall of the Hittite empire, especially in south-eastern Anatolia. The discovery of these graffiti suggests that by the middle of the 2nd millennium the practice of Luvian hieroglyphic writing must have been more widespread than previously thought.

Although Hattusha, the capital of the Hittites, has been continuously excavated for more than a century, it still has many secrets to reveal. Yet the question of when this hieroglyphic writing appeared in Anatolia remains unanswered.