The extinction of cuneiform writing

31 August 2020

Cuneiform scripts, in use throughout the Near East for more than three millennia, slowly died out during the first millennium BCE and finally disappeared in the first century CE. It was not until the 19th century that they were rediscovered. How can we explain this disappearance of a script that had been used to transcribe languages belonging to different linguistic families, and especially the oblivion surrounding it?

How could the ancient Mesopotamians, who wrote down everything they needed and scrupulously archived their clay texts, have abandoned their writing and the Akkadian language?

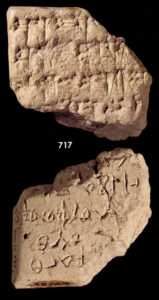

The phenomenon did not happen overnight; it was spread out over the whole of the first millennium BCE. From the beginning of this millennium, Aramaic, one of the West Semitic languages, was used in Mesopotamia in parallel with Akkadian. This language was written on a flexible medium, papyrus or skin, with ink, using the Aramaic alphabet, a consonantal alphabet of 22 letters written from right to left. Unlike the clay tablets, which have stood the test of time, the papyri and skins, organic materials, have disappeared. The cuneiform texts give the names of scribes who specialised in writing Aramaic texts on skins and testify to their production. These texts were archived in the form of scrolls alongside cuneiform tablets, and sometimes a clay label written in cuneiform was attached to the end of the scroll to indicate its contents. This label is all that remains today.

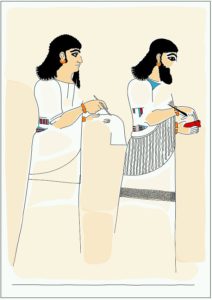

Frescoes and bas-reliefs from the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-612) show the concomitant use of both writing systems. The lead scribe holds a tablet in his left hand and a stylus in the right, while the second scribe holds a flexible medium and writes on it with ink. Aramaic texts written on clay are rare, cuneiform signs written in 2D are exceptional; these writings are clearly adapted to their medium.

Southern Mesopotamian tablets were discovered in temples or in the houses of individuals working for the temples. They include administrative and economic texts, letters, and literary and scholarly texts. After the arrival of Alexander the Great in Mesopotamia in 331 BCE, Akkadian, written in cuneiform, was used only in Babylon and Uruk among the clergy. Aware of the disappearance of his brilliant civilisation, Berossus wrote for King Antiochos I (281-261) the Babyloniaca (History of Babylon), going back to before the Flood. The work is lost but excerpts have been copied.

The last cuneiform archives dated to the last three centuries BCE come from the libraries of scholars, from those of the exorcists of the temple of Uruk, and in Babylon from the administrative archives of the temples and of the notables working for the temple, such as the brewers and the astrologers who left astronomical records. The texts, which are often faulty, show that their authors had a poor command of their own language and also regularly wrote in Aramaic.

Some twenty texts that Assyriologists call graeco-babyloniaca date from this period. On one side, a text is written in Akkadian or Sumerian cuneiform, while on the other side we find the phonetic transliteration of the text in Greek letters. The aim was to teach the pronunciation of Akkadian and Sumerian to the Babylonians who had lost contact with their language.

The last texts, dated to the 1st century BCE and CE, are astronomical texts: observation reports, tables, ephemerides and procedural texts. There was therefore still at least one scribe in a Babylonian temple capable of writing and understanding Akkadian. The latest text to be discovered dates from 75 CE, and it is not unlikely that others will resurface. The Mesopotamian civilisation subsequently fell into oblivion until travellers cleared its ruins and deciphered cuneiform writing less than two centuries ago.