What can we learn from fingerprints on clay?

31 August 2019

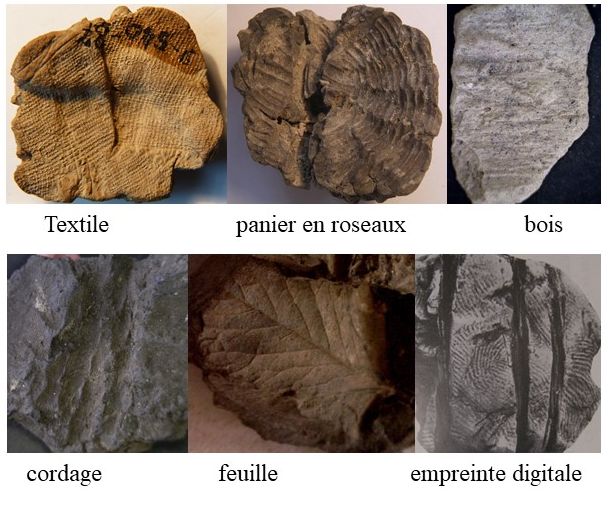

Dishes, labels on containers or bundles of goods, even cuneiform tablets, all objects made of finely prepared clay, regularly show imprints of other materials. This may be the weft of a textile that was used to close a vase or protect a tablet, or traces of reeds from a basket or wood from a chest. Occasionally, we also find the imprint of a leaf or a feather that was lying near the clay object when it was drying.

But the most numerous imprints are often those of the fingers of the person who shaped the clay object. Until a few years ago, researchers paid little attention to these fingerprints. Today, their study opens up new perspectives on craftsmen and scholars.

For over a century, fingerprints have been used by forensic scientists to identify criminals. Dermatoglyphics, or patterns on the palms and fingers, have ridges and folds. Recent research on the distribution and density of ridges in fingerprints has shown differences between female and male fingerprints. Women have thinner ridges than men and therefore have a higher ridge density.

With this new knowledge, archaeologists examined fingerprints on ceramics unearthed at Tell Leilan in the Habur Triangle in Syria and dated to the late fourth to early second millennium BCE. These ceramics were initially produced by adult men and women, but from the middle of the 3rd millennium, as the phenomenon of urbanisation intensified in Upper Mesopotamia, they were mostly produced by men. The creation of increasingly large cities and the centralisation of the state would therefore have contributed to the intensification of a gendered division of labour.

Similar observations were made by an international team that analysed the fingerprints of more than 400 ceramics discovered in Hama, Syria. Not only were the ceramics produced by men from the middle of the third millennium onwards, but they also contained fingerprints of young boys as young as eight years old. These bear witness to an early apprenticeship, and to the professionalisation of the these craftsmen. The phenomenon is confirmed by textual documentation from southern Mesopotamia dating from the end of the third millennium.

The first attempts to analyse fingerprints on cuneiform tablets date back to the 1980s, but they have not yet been carried out systematically on a coherent corpus. Assyriologists have been wondering for many years about the identity of the individuals who wrote these cuneiform texts, since texts signed by their authors remain exceptional. Palaeographic studies reveal different "scribes' hands", and the analysis of fingerprints, when visible, may confirm the attribution of specific documents to a scribe. Depending on the period and the culture, we now know that the practice of writing was not necessarily reserved for an elite, but could be relatively widespread, among both men and women. The analysis of fingerprints on cuneiform tablets could reveal the proportion of women who wrote these texts. Fingerprint analysis of scholastic tablets would also provide information on the age at which children began learning and the length of time they spent learning.

Thanks to technological advances – precision 3D scanners, recognition programmes, powerful databases – this study can be carried out on the hundreds of thousands of cuneiform tablets that we are still deciphering.