A record auction for a Neo-Assyrian relief

15 December 2018

On 31 October 2018, an inscribed Neo-Assyrian relief was sold on auction at Christie's New York for almost $31 million. This record sale for an ancient Near Eastern artifact has unfortunately significantly increased the risk of encouraging trafficking in antiquities.

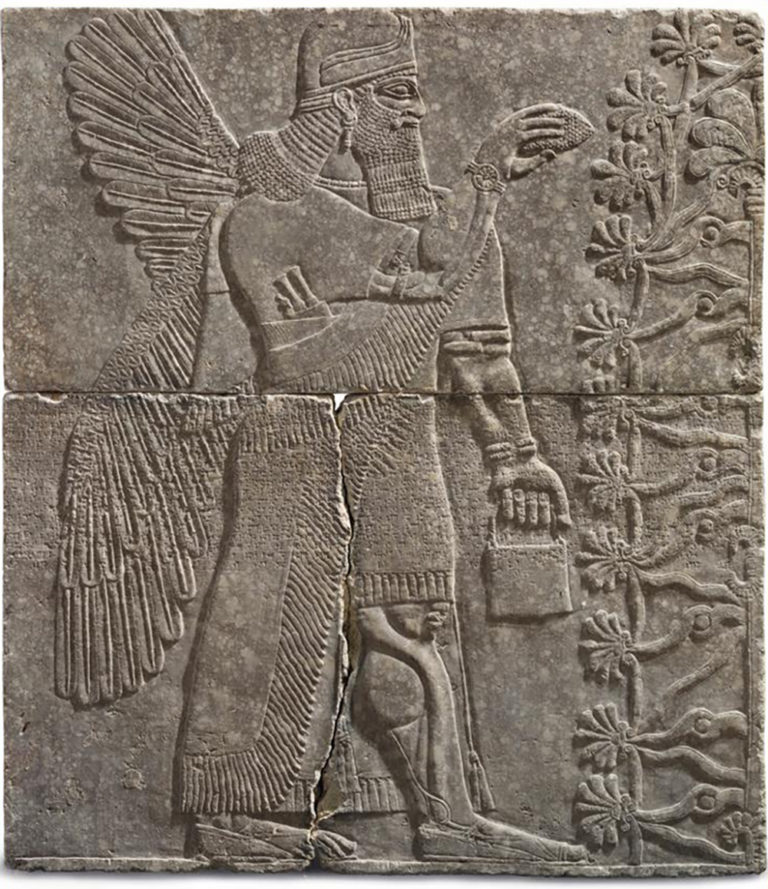

This is a gypsum panel over 2 metres high from the palace of Assurnazirpal II (883-859 BCE). The palace is located northwest of the site of Nimrud (Iraq, 35 km south of Mosul), the ancient Kalhu, one of the Assyrian capitals. The relief depicts a winged genie, whose head is reminiscent of those of the Assyrian rulers of the first millennium: his hair and beard are finely curled, and he carries a bucket-shaped vessel in his left hand and a pomegranate in his right hand. Originally, these reliefs were painted in bright colours; traces of pigment found on similar reliefs give an idea of the original appearance of this one.

The relief is partially covered with a cuneiform text referred to by Assyriologists as the "Standard Inscription" of Assurnazirpal II. The panel was part of a large ensemble that decorated the walls of the palace and this inscription, which commemorates the ruler’s military conquests, was repeated on more than three hundred panels. The text begins with a title that confirms the legitimacy of the king, chosen by the gods and descended from a long dynasty of rulers, and that praises his martial qualities. This is followed by the main military campaigns and the long list of defeated territories. It ends with the restoration of the city of Kalhu, chosen by the king as his new capital, and a detailed description of the construction of the north-western palace and the inauguration of the capital, celebrated with a gargantuan banquet.

How did this relief end up in an auction room? Kalhu was explored between 1845 and 1851 by Austen Henry Layard, a young British diplomat, who soon abandoned the site to focus on Nineveh. In his first days of excavation, he found the north-western palace and then a room covered with large inscribed Neo-Assyrian reliefs. With the approval of the Ottoman Sultan's Grand Vizier, Layard soon sent his findings to England where they formed the core of the British Museum's Assyrian collection. A group of American missionaries working nearby took an interest in the young Briton's discoveries and found echoes of them in the Bible, and in 1859 one of them, Henry Byron Haskell, bought several relief panels for $75 each to send to the Virginia Theological Seminary. He also sent some to Bowdoin College in Maine, one of which is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. As Layard partly financed his excavations by selling antiquities, many of today’s collections around the world include Kalhu reliefs. The monumental reliefs were on display in the library of the Virginia Theological Seminary until an audit in 2017 reassessed their value. In order to pay the insurance premiums for these panels and to create scholarships, the institution decided to sell one of them.

As these reliefs were sent to the United States in the 19th century, they are not covered by the law on antiquities that came into force in Iraq in 1924, nor by the UNESCO convention of 14 November 1970 on the protection of cultural property. Nevertheless, the Iraqi Ministry of Culture, as a matter of principle, requested the restitution of the panel before its sale by auction. This type of sale is alarming: not only does it risk increasing the price of Mesopotamian antiquities – even though their sale is forbidden – but it will also have the collateral effect of encouraging more looting, which has been ongoing for the past ten years.