Which roles did women play in the Epic of Gilgamesh?

29 September 2018

A fragment of a recently published tablet sheds new light on the role played by Shamhat, the prostitute who transformed Enkidu into a civilised being in the Epic of Gilgamesh.[1] Gilgamesh was the king of the city of Uruk; he was a sort of Sumerian Hercules who, carried along by his adventures, encounters various characters with whom he has either conflictual or amicable relations.

Here we can take the opportunity to examine the roles played by women in an epic written by men for a male audience, which focuses on two male heroes: Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu.[2] These female characters, fully integrated into Uruk society, have different fates: two of the women are defined by their relationships with a man, while the other two lead independent lives dedicated to men’s ‘leisure’.

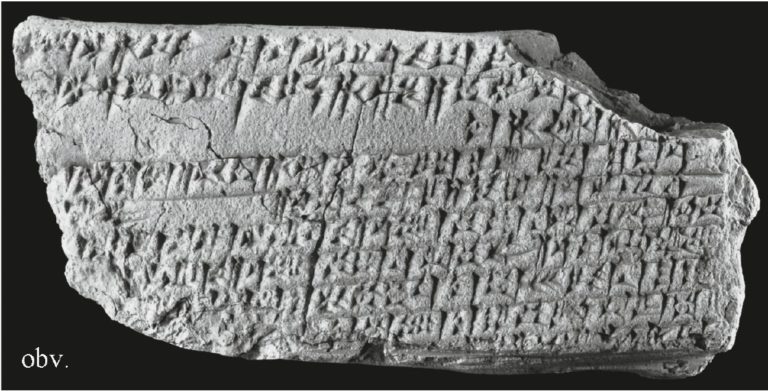

The new fragment, which dates from the Palaeo-Babylonian era (at the beginning of the second millennium BCE), makes it possible to complete the ancient version of the epic known at present through 16 tablets or fragments of tablets.[3] Unfortunately, the new fragment originates from illegal excavations, and its lower portion has been artificially cut so as to make it seem like an intact object. Today, it is kept in Cornell University’s collection, but along with almost 10,000 other tablets in the same collection it ought now to be sent back to Iraq. The new text enables us to reconstruct in detail Enkidu’s encounter with Shamhat and to better understand his psychological development during his ‘humanisation’ process.

Shamhat, the prostitute, has a paid job which enables her to support herself: she works to ‘service’ men. Gilgamesh entrusts her with the task of seducing and ‘taming’ Enkidu, the wild man. She reveals her charms, makes love to Enkidu and tries to convince him to accompany her to Uruk to meet Gilgamesh. However, after a week or so, Enkidu retains his animal instinct and tries to regain his life among the wildlife, who duly rebuff him because he has been intimate with the enemy. There then follows a second week of sexual intimacy (which is scarcely described) during which the prostitute changes her tune: at Uruk, Enkidu will find a role to play in human society and could become a ‘man’ and participate in the nurturing of the gods in their temples. Shamhat is depicted as a shrewd woman, one who is maternal in nature and full of good counsel, even though in Mesopotamian society the prostitute represents a threat to the stability of the family unit.

The other women who appear in the epic are also maternal types. To start with, there is Ninsoun, the divine mother of Gilgamesh, who has also given birth to the gods Nergal and Doumouzi. A loving mother, she interprets her son’s dreams and comforts him. At the same time, she criticises the Sun god Shamash for having made his son an adventurer and hopes fervently that he will assist him in his struggle against Humbaba, the guardian of the Forest of Cedars.

Without doubt, the most interesting character is Siduri, the hostess who, like the prostitute, works for a living. She delivers philosophical speeches brimming with pearls of wisdom. She tries to dissuade him (i.e. Enkidu) from pursuing his quest for immortality, and advises him to enjoy the pleasures of everyday life: good food, being well dressed, and having a wife and children, thereby extolling the virtues of Mesopotamian societal norms.

The wife of Utnapishtim, the survivor of the Great Flood, is not explicitly named in the epic, and she plays a passive role in the account of the flood given by her husband to Gilgamesh. On the other hand, she tries to intervene on behalf of Gilgamesh by appealing to her husband and reminding him of the rules of hospitality. She then reveals to Gilgamesh the existence of a plant that bestows eternal youth. The interventional role played by Utnapishtim is reminiscent of the role played by mothers and wives in Mesopotamian literary texts.

The Epic of Gilgamesh offers a description of Sumerian society through types. Half of the women occupy roles that keep them within the family setting, whilst the other half have jobs that provide them with a personal income and afford them independence. Hence the female characters reflect the hopes and fears of men, but also the diverse and ambiguous characteristics of the lives of women.

[1] Bottéro, Jean (1992), L’Épopée de Gilgameš: Le grand homme qui ne voulait pas mourir, Paris: Gallimard.

[2] Michel, Cécile (2010), Le petit monde de Sumer (Dossier L’Épopée de Gilgamesh), L’Histoire 356, 58-61.

[3] George, Andrew R. (2018), Enkidu and the Harlot: Another Fragment of Old Babylonian Gilgameš, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, 108, 10-21.