At the ancient Mesopotamians’ dinner table

29 June 2018

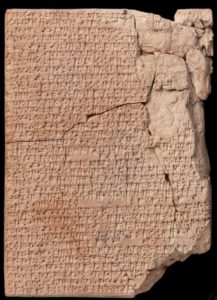

Some researchers at the universities of Yale and Harvard have cooked three Babylonian stews whose recipes were gleaned from four cuneiform tablets, dating from the eighteenth century BCE, held at the Yale Babylonian Collection.

The dishes were presented at the end of April as part of a symposium titled ‘An Appetite for the Past’, organised by the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at the University of New York. This initiative was not altogether new. At Brown University, Alice Slotsky for years organised an annual reception where the dishes offered were prepared in accordance with these Babylonian recipes. But what exactly was served on the meal tables of the ancient Mesopotamians?[1]

These recipes chiefly concern the preparation of broths and meat stews, but address pie making as well. They never specify the quantities of the ingredients (with sometimes unfamiliar names), nor cooking times. The recipe for the small foul pie is rather sophisticated: the birds and their giblets are cooked in broth; then they are placed between two sheets of pastry made from milk and semolina flour. Some dessert recipes could be reconstructed working from coeval notes specifying ingredients kept in the palace’s stores for the preparation of the monarch’s daily meals. One such dessert consists of a pastry made from flour and butter which is then filled with dates, raisins, figs, apples and pistachios, together with sugar and honey flavoured with cumin and coriander. The pasty prepared thus is then oven baked.

In the first millennium BCE, the royal annals and the bas-reliefs that decorated the kings’ palace described and depicted the sumptuous court banquets held there. Several of the depictions celebrate military victories or the realisation of major works. Thus, the Banquet Stele of Ashurnazirpal II (ninth century) depicts the feast that accompanied the inauguration of the new capital, Kalhu. The stele illustrates in detail the foodstuffs offered by the king to his 69,574 guests during the ten days of festivities.

The meals eaten by the common people were a lot more basic. They ate two meals a day; a gruel upon getting up in the morning, and something a bit more ample in the evening. Cereals, above all barley, and less often emmer wheat and spelt, constituted the staple foods, in the form of flours, gruels and leavened or unleavened bread. Their main beverage was ale, which was made daily by the womenfolk and based on the maceration or fermentation of barley. There were numerous varieties: black ale, light ale, red spelt ale, premium quality ale, triple ale, clarified ale, etc. Sesame oil was used for food preparation, lighting and body care treatments. Starchy vegetables, fava beans, peas or lentils, used as purées or grilled, were supplemented with various types of alliaceous plants: garlic, onions and leeks. Spices and aromatic herbs, also grown in kitchen gardens or gathered in the countryside, were added to dishes to enhance their flavour: salt, pepper, mustard, thyme, rue, coriander, cumin, etc. Various fruits were grown in orchards: dates, figs, apples, pears, pomegranates, grapes, walnuts, almonds, pistachios, and so on. The consumption of wine was widespread, but must have been less common in the homes of people of low social status. Mutton was the chief meat in the diet. Pigs were raised and their meat consumed up until the first millennium, above all in rural areas. At Nuzi, some of the people had a taste for horse meat. Ducks and other foul were appreciated for their meat and eggs. Meat was dried, salted and smoked, and used in soups, stews and pies, and as roasts. Rich and poor alike ate fresh, dried, salted and smoked fish.

The Babylonian recipes kept at Yale are the only ones that have come down to us. They have been masterfully translated by the Assyriologist Jean Bottéro. Nonetheless, despite being an excellent cook, he has always declined to try them out, explaining that tastes have changed too much in the space of four thousand years. Instead, he has preferred to imagine the ancient flavours by tasting the products of Arab-Turkish, Lebanese and Near Eastern cuisines, which are without doubt the descendants of a multi-millennial tradition.

[1] Lion, Brigitte and Michel, Cécile (2003), Banquets et Fêtes au Proche-Orient ancien, Dossiers d’Archéologie 280.