When Mesopotamians sent enveloped letters

30 June 2017

Today, almost everyone writes letters – or rather, e-mails! This literary genre has a long history; according to scribes at the start of the second millennium BCE, writing was invented specifically to address the need for long distance communications.

The legend of Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta recounts the birth of such exchanges between kings, and therefore of diplomatic correspondence: ‘(Enmerkar) shaped the clay and wrote on it a message, as one does on a tablet. Before that time, the writing of messages in clay did not exist’. When he received the piece of clay, the Lord of Aratta, who was illiterate, regarded it with a puzzled expression, being unable to understand the message. A letter is only useful if it has a recipient, and moreover if that recipient is able to read its content. In actual fact, the epistolary genre appears relatively late in the history of cuneiform writing; indeed, the most ancient letters that have been discovered up till now only date from the second half of the third millennium BCE, which is to say about a thousand years after the first appearance of writing, the operation of which was then sufficiently evolved to make it possible to set down texts of this kind.[1]

At the beginning of the second millennium BCE, the use of letters was quite widespread. Each and every day, the scribes would consume a large amount of clay to make their tablets – to write letters, amongst other things, as witnessed by this one drawn from the diplomatic correspondence of Mari (on the Euphrates, eighteenth century BCE): ‘I have used up all the clay in the town of Ashnakkum for writing letters that I never cease to despatch!’. This evokes an impressive image, since clay was an abundant material in Mesopotamia, and it cost very little. However, the quality of the clay was important; it ought not contain any impurities. Furthermore, letters were generally no larger than the palm of one’s hand; larger tablets were more difficult to transport and the risk of breaking them was greater. One finds letters consisting of just two or three lines, like that jotted down by the wife of an Assyrian merchant who complained of not receiving news about a family member: ‘Why do you not send me your greetings on a tablet, even just a couple of lines?’. Conversely, we also encounter some letters consisting of around a hundred lines, but this made it harder to create an envelope…

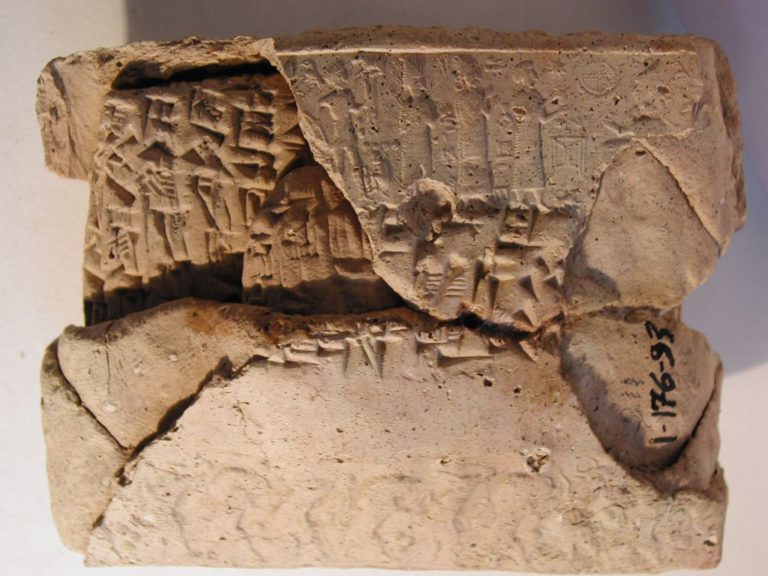

Indeed, letters were sent in ‘envelopes’: once they had been dried in the sun, the inscribed tablets were coated in a thin layer of clay.[2] This envelope protected the tablet and the writing it bore during its conveyance. The sender rolled their cylinder seal across the envelope, and wrote on it their name and that of the recipient of the message. When the letter arrived at its destination, the recipient cracked the envelope open in order to read the letter. Some letters required the use of two tablets, the scribe having miscalculated the amount of space he needed for his writing; the two ‘pages’ were then placed inside the same envelope. Needless to say, when the envelope was opened in ancient times, the two pages were separated, so today it is difficult reunite them. Normally, the discovery of envelopes would be very unusual; however, some letters found today are still conserved intact within their envelope. One must therefore deduce that these letters arrived when the recipient was absent or had perhaps died, and that they were kept as they were when they were delivered, or alternatively that they represent copies of letters, kept by their senders.

[1] Michalowski, Piotr (2011), The Correspondence of the Kings of Ur. An Epistolary History of an Ancient Mesopotamian Kingdom, Pennsylvania: Eisenbrauns.

[2] Legally binding documents were also sealed within a clay envelope upon which the text was copied out. Witnesses and interested parties also rolled their cylinder seals over the envelope. Thus, the envelope endowed the text with its legal value. Once it was cracked open, the document lost its legal character.