Some new techniques to identify the authors of cuneiform texts

25 May 2017

This month, as we celebrate the 160th anniversary of the decipherment of cuneiform transcriptions of the Akkadian language[1], Assyriologists are attempting to answer the following questions: who were the authors of the cuneiform texts? And was writing the exclusive preserve of professionals, or was it more widely practiced?

The scribes, who produced thousands of scholastic tablets as part of their training, composed letters and contracts for individuals, in addition to working for the king. We know the identities of very few of them – chiefly men, but also some women. Sometimes they would place their name on the contracts they wrote, which they also served as witnesses for; less often, they would leave their names on school exercises. Even so, most remain anonymous, because the majority of texts do not bear the writer’s name (letters, royal inscriptions, literary texts, etc.).

But are all the writers of cuneiform texts scribes who made a living from drafting texts for third parties? Some recent studies have shown that, depending on the period and milieu concerned, the practice of writing seems to have been more widespread than we had imagined up till now. For example, the Assyrian merchants who were established in Central Anatolia at the beginning of the nineteenth century BCE used writing to help them conduct their long distance trade. In their dwellings located in the lower town of Kültepe (ancient Kaneš), they left around 23,000 cuneiform tablets that constituted their private archive. Side by side with the professional scribes, who were trained at Aššur and worked for the trading post, large families of Assyrian entrepreneurs or the Anatolian government, some of the merchants pursued the basic writing course with the master scribe. The scholastic texts discovered in the houses at Kaneš bear witness to schooling that was completely focused on the trading profession (e.g. conversion exercises to learn how to calculate the price in silver for a given weight of gold, tin or copper). Other merchants, along with a few women and some foreigners, learnt the rudiments of writing and arithmetic at home, knowledge that was passed on to them by their fathers or brothers. The texts they wrote provide evidence of on-the-job training: poorly shaped tablets, a rather limited syllabary, badly written signs, grammatical errors, etc.

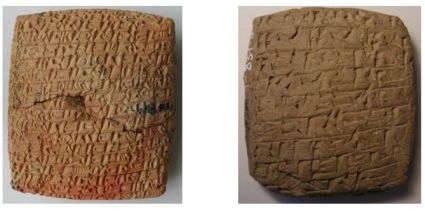

Today, Assyriologists are attempting to identify the different writing hands of scribes, with the aim of estimating the proportion of the population that was able to read and write. In addition to the shaping of the tablet and its layout, they study stylometry (i.e. style of the text), the choice of signs, and the range of the syllabary employed. They pay particularly close attention to the gap between two lines, and above all to the way in which the signs were imprinted into the soft clay: upright or slanted, the number and position of the wedges that form a sign, the order in which the wedges were impressed, and the material and shape of the stylus, etc.

Three-dimensional scanning and digital manipulation of images make it possible to obtain very precise measurements of the concave imprints left by the stylus. Henceforth it will be possible to predict the shape of the stylus’s tip, depending on its trajectory when it was pressed into the clay. A statistical analysis of the geometric properties of styluses, of the angle they formed with the surface of the tablet during the impression of a wedge, and the order in which the wedges were impressed when a sign was made in the soft clay, make it possible to characterise the handwritten text on a tablet and, indeed, the scribe. These methods facilitate not only the identification of different writers of texts, but also the reconstruction of shattered tablets by joining fragments which have been dispersed throughout numerous collections across the world. Thanks to quantitative palaeography and script metrology, Assyriologists will be able to estimate the number individuals that produced a specific group of cuneiform tablets.

[1] Lion, Brigitte and Michel, Cécile (2016), Les écritures cunéiformes et leur déchiffrement, Paris: Editions Khéops.