At the school for scribes: writing and counting in cuneiform

29 January 2017

‘I read my tablet, I ate my lunch. I prepared my fresh tablet, I filled it with writing, I completed it. Then I was told what to read, and in the afternoon I was informed of my writing exercise. At the end of the class, I went home; I entered my house, where I found my father seated. I spoke about my writing exercise to my father, then I read my tablet and my father was very pleased.’

This extract from a school text written in Sumerian shows that, 4,000 years ago, the apprentice scribes of Babylon learnt to read and write in Sumerian, a dead language that was used in written culture and for making calculations.

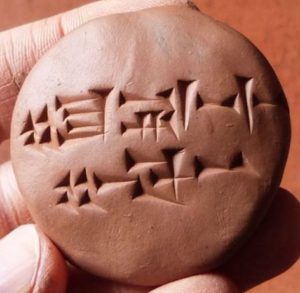

Thousands of school tablets, mostly discovered at sites in southern Mesopotamia and dating from the first half of the second millennium BCE, have made it possible for Assyriologists to reconstruct the curriculum followed by the pupils of old. They most likely went in small numbers to a master scribe’s abode where they first learnt to shape their clay into a lenticular form (i.e. a flattened ball, the easiest shape to make), and then into a rectangular tablet. Next, they learnt how to grasp their reed stylus. Like small children at today’s nursery schools, the young scribes then started to make wedge-shaped impressions in the clay, the basic component of cuneiform script being the horizontal wedge, the vertical wedge, and the head of a wedge (or Winkelhaken). Next, they copied (so as to memorise) the syllabic signs in fixed sequences: tu-ta-ti, bu-ba-bi… Following this, they had to copy out and learn lists of thematically classed words. Initially they knew only Sumerian, but a few centuries later the scribes would became bilingual, when they translated texts into Akkadian. They also copied and learnt lists of signs based on their shape, their sound, or their meaning. Finally, they copied out proverbs and models of legal contracts. In an advanced phase of the training course, the apprentice scribes would copy out literary texts.

Concurrently, the pupils learnt to count and write down numbers according to the sexagesimal positional system. The numbers 1 and 60 were represented by the same sign: a simple upright wedge. An intermediate decimal base with a distinctive sign for 10, the Winkelhaken, made it possible to simplify writing numbers. From 1 to 9, the appropriate number of vertical wedges (as units) were added. These were generally placed in groups of three, so as to facilitate rapid reading. In the same way, tens were written by adding the sign for 10, still in accordance with an additional mathematical notation. This way of writing numbers was positional insofar as, according to the respective positioning of two identical signs, it was possible to write two different numbers. On the tablet shown below, on the last line, the Winkelhaken followed by a vertical wedge equals 11 (10+1), whereas the vertical wedge followed by a Winkelhaken equals 70 (60+10). There was no sign for zero; a single vertical wedge can be read as 1, 60, 60 x 60, or 1/60; this system therefore represented a ‘floating’ notation. We have inherited the Mesopotamian sexagesimal system for measuring time and angles. As they practiced writing sexagesimal positional numbers, the apprentice scribes learnt metrological lists and tables off by heart (capacities, weights, areas, lengths), as well as numerical tables (inverse numbers, multiplication, squares, square roots, etc.). They also gained an insight into making calculations (e.g. multiplication, calculation of areas and volumes, etc.).

An exhibition of cuneiform writing organised by Laetitia Graslin-Thomé, Senior Lecturer at the University of Lorraine, is currently being held at the University Library of Letters, Humanities and Social Sciences at Nancy, in France. The exhibition is open to the public until 24 February. Some associated workshops to demonstrate cuneiform writing on clay have been organised by a group of students (scheduled to take place on Thursday afternoons).

Online conference: ‘Cuneiform writing in the ancient Near East: teaching, learning and key players’, Transmission of knowledge: the Archaeology of Learning, a meeting of the INRAP, City of Sciences and Industry, La Villette, Paris (link added in November 2017).