Mesopotamia honoured at Louvre-Lens

14 November 2016

Louvre-Lens is presenting a major exhibition which will run from 2 November to 23 January 2017, whose title, ‘History Begins in Mesopotamia’, echoes the well-known work by Samuel Noah Kramer, the eminent American scholar of Sumerian, History Begins at Sumer.[1]

The original title of the book was ‘From the Tablets of Sumer: Twenty-five Firsts in Man’s Recorded History’. Upon its publication in the United States in 1956, the work enjoyed some success, as S. N. Kramer himself recounts in his autobiography.[2] At the time of its translation into French and its publication by Arthaud Editions, Jean Bottéro, a renowned Assyriologist, proposed changing the work’s title to ‘History Begins at Sumer’. Published in its French language version in 1957, the book enjoyed an immediate success, and that year received the prize for the best foreign work published in France. The book was acclaimed by André Breton and swiftly translated in other European countries. In 1959, the American publishing house Doubleday, which had initially turned down the book, decided to publish the work as a paperback under the new title. Since then, the book has remained the uncontested bestseller on Assyriology all over the world.[3]

The exhibition at Lens was inaugurated on 1 November by the President of the Republic, François Hollande. The President decided that it should be held when he visited the Louvre in March 2015; this was a political decision that highlighted France’s serious concern for the ruination of the archaeological patrimony of the ancient Near East, in particular in Iraq and in Syria, which has been going on for too long. To organise such an ambitious exhibition in just 18 months represented a real challenge for the conservators of the Louvre and the Louvre-Lens – a challenge that was successfully met by Arian Thomas, the superintendent of the exhibition, working in conjunction with his colleagues. The exhibition was designed to help the public rediscover the richness of ancient Mesopotamia, a civilisation that to a great extent inspired ours, but which all too often remains unsung.

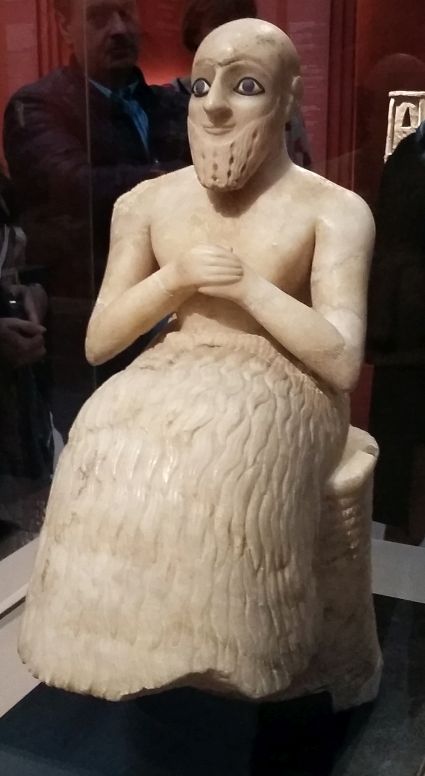

More than 400 objects, mostly originating from the Louvre’s depository, illustrate Mesopotamian innovations through a series of exhibits dedicated, successively, to the rediscovery of Mesopotamia, its economy, its religion, the first cities, the first writing, the early kings, the first dynasties, and the first empires. For those who are unable to visit the exhibition, a sumptuously illustrated catalogue showcases the items on display and offers the reader the chance to take a ‘tour’ of ancient Mesopotamia’s numerous innovations.

Some other major exhibitions are celebrating the grandeur of the ancient Near East. In Rome, since 6 October, and continuing until 11 December, visitors to the Coliseum can admire some life-size reproductions of three monuments which today sadly no longer exist, having been destroyed: the human-headed winged bull of Nimrud (ancient Kalhu); the archive room of Ebla; and part of the ceiling of the Temple of Bel at Palmyra. The remains of the ‘Pearl of the Desert’ are also honoured at the Grand Palais from 14 December until 9 January, as part of the exhibition titled ‘From Bamiyan to Palmyra, a Journey to the Heart of World Heritage Sites’. Thanks to some 3D reconstructions, visitors will be plunged into the heart of four endangered or partially destroyed archaeological sites: Khorsabad, Palmyra, the Krak of the Knights, and the Umayyad Mosque (i.e. the Great Mosque) of Damascus.

While the battle is underway to retake the towns of Mosul and Raqqa from the jihadists of ISIS, and when the people of Aleppo are under siege and starving, it is good to remember the grandeur of the Mesopotamian civilisation that we have partly inherited.

[1] KRAMER, Samuel N. (1988), History begins at Sumer, third edition, Philadelphhia: University Pennsylvania Press.

[2] KRAMER, Samuel N. (1986), In the World of Sumer. An Autobiography, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, chapter 9: ‘Birth of a Best-Seller’, 135-143.

[3] A French work of collective authorship had already been inspired by the title: Pierre Bordreuil, Françoise Briquel-Chatonnet and Cécile Michel (eds.) (2014), Les débuts de l’histoire. Civilisations et cultures du Proche-Orient ancien, Paris: Editions Khéops, (first edition: La Martinière 2008).