The decipherment of cuneiform writing: A complex matter!

8 May 2015

Between the time of the final abandonment of cuneiform script in the first century BCE and the exploration of the Near East by Western travellers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries ce, the history of Mesopotamia was completely forgotten — or almost completely forgotten.

All that remained in the collective memory were a few places mentioned in the Bible and in the works of the Greek historians: the Tower of Babel, Kalhu, Nineveh, the so-called Hanging Gardens of Babylon and a few imaginary figures, inspired by renowned Assyrians and Babylonians, such as Semiramis and Sardanapalus.

In 1786, the deposit of the Caillou Michaux in the Cabinet des Médailles in the Bibliothèque Nationale marked the arrival of the first object bearing an inscription in cuneiform text in Europe. The interpretations proposed for the text engraved on the object were completely outlandish. The process used for the decipherment of these entirely unknown writings is long and complex. In fact, in contrast to Egyptian hieroglyphics and Linear B, which record single tongues, cuneiform was used to record about a dozen different languages.

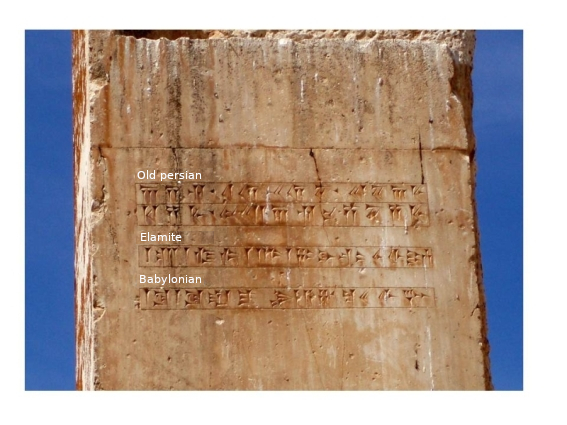

Just like Jean-François Champollion, the scholars of the nineteenth century worked on trilingual texts. But if the Rosetta Stone bears three languages and three different types of script, including Greek, the three languages inscribed on the bas-reliefs and clay tablets all use cuneiform characters. The first scholars who attempted to understand the way in which this writing system worked employed the technique known as ‘decipherment’, which is to say the decryption of the written (or ‘encoded’) message.

During a journey he made to Iran in 1763, Carsten Niebuhr (1733–1815), the Danish mathematician, counted the number of signs employed in each version of the trilingual inscriptions at Persepolis. He identified three different cuneiform writing systems which are read from left to right, and concluded that the most simple system uses an alphabet composed of 40 signs. Georg Friedrich Grotefend (1775–1853), a young classical philologist, concerned himself with this simplest of systems. He looked for repeating sequences, and tried to identify proper nouns. He examined royal inscriptions dating from the Achaemenid era which necessarily included the names of one or more Persian kings known through the texts written by Greeks of the classical period. He deduced that the transcribed language was an ancient form of Persian, an Indo-European language known through the ancient and sacred Zend-avesta. Grotefend isolated some repeating sequences and interpreted them as meaning ‘King, son of […] King, King of Kings’; he also recognised the names of Darius and Xerxes. In addition, in the year 1802 he identified a quarter of the signs in the Old Persian cuneiform alphabet.

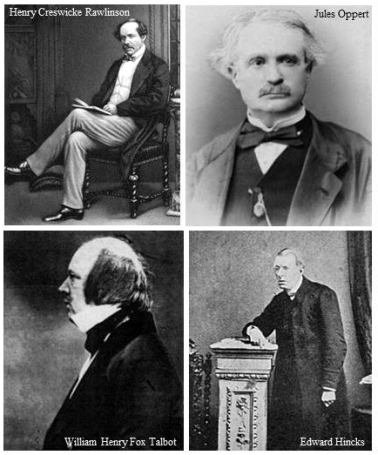

The work of deciphering this alphabet was completed 45 years later by Henry Creswicke Rawlinson (1810–1895), an officer of the British East India Company who, meeting the considerable challenge, managed to copy down the immense trilingual inscription of Darius I at Behistun. The Old Persian alphabet, used between the sixth and fourth centuries BCE, is the simplest and most recent cuneiform writing system.

Once the decipherment of Old Persian had been achieved, the scholars found themselves in a situation similar to that Champollion had found himself in; from this point on they knew the content of the trilingual cuneiform texts of Persepolis. The scholars supposed that one of the two other languages was Semitic, and that the majority of the signs represented syllables; this explained their substantial number. The inscriptions and cuneiform tablets written in this script, subsequently called Akkadian (derived from the name of the Akkad region) grew and grew, thanks to the excavations carried out by some British and French diplomats in the north of Iraq, which began in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Four scholars, all of them excellent philologists, worked simultaneously on the decipherment of this Semitic language. At the same time both colleagues and rivals, they continually exchanged views. Henry Rawlinson, having succeeded in deciphering Old Persian, identified the proper nouns in the Akkadian version inscribed on the rockface at Behistun, and went on to publish a book containing the latter in 1851. Jules Oppert (1825–1905), a German Jewish scholar who had settled in France, went to the British Museum to study the tablets originating from the library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, and participated in an expedition to Mesopotamia between 1852 and 1854. Upon his return, he wrote a report showing that he had understood the principles underlying Akkadian notation and the way in which the language worked.

Henry William Fox Talbot (1800–1877) was just as interested in botany and mathematics as in philology and archaeology. He was also an inventor: his calotype (1841) made it possible to obtain multiple positive photographic images from a single paper negative. To put his invention to good use, he went to the British Museum and photographed the bas-reliefs from Nineveh. This led him back to his passion for philology; he exchanged views with other scholars of the period, including Edward Hincks (1792–1866). The vicar of a small town in Ireland, Hincks, in contrast to his colleagues, scarcely moved any distance from his home. After doing some noteworthy work on hieroglyphics, he turned his attention to the decipherment of the Behistun inscription, discerned the name of the King of Judea on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, and identified the god of Assyria on the reliefs at Kalhu.

In 1857, on the request of Henry Fox Talbot, the Royal Asiatic Society decided to send to its scholars copies of an inscription of the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I (1113–1074), which had just been unearthed. Their translations into English were delivered in sealed envelopes and were opened on 25 May 1857, by a specially assembled commission: largely speaking, the translations coincided, so that date marks the moment when Akkadian written in cuneiform script was successfully deciphered. The use of Akkadian is attested from the middle of the third millennium BCE up until the abandonment of cuneiform script. Starting from the beginning of the second millennium BCE, Babylonian split into two main dialects, used in the North and in the South. The third language written using a cuneiform syllabary in the inscriptions of Persepolis and in the rockface at Behistun is Elamite, a language whose linguistic family has not, as yet, been identified.

Some other languages that used cuneiform script were yet to be discovered. Some bilingual tablets from Nineveh bore a version of Akkadian and a text written in an unknown language. E. Hincks suggested that the writing in cuneiform was not of Semitic origin, whilst J. Oppert imagined that the signs that composed the aforementioned unknown language did not correspond to syllables but instead to words: he named this idiom ‘Sumerian’, based on the title ‘King of Sumer and of Akkad’ adopted by certain Mesopotamian kings. Some tens of thousands of tablets inscribed in Sumerian were unearthed in the last quarter of the nineteenth century in southern Mesopotamia. At the beginning of the twentieth century, François Thureau-Dangin (1872–1944) published some Sumerian royal inscriptions. The decipherment of Sumerian, which continued for the duration of the twentieth century, was partly based on the bilingual lexical lists employed by the scribal apprentices who were required to learn, from the beginning of the second millennium onwards, this dead language.

The decipherment of Hittite, the first Indo-European language written with the aid of the Akkadian cuneiform syllabary, was achieved by the Czech scholar Bedřich Hrozný (1879–1952) in 1915. In 1933, Johannes Friedrich (1893–1972) deciphered Urartian, a language used in the lake Van region between the eleventh and ninth centuries BCE. Eblaite, attested in Syria in the twenty-fourth century was discovered at the eponymous site in 1975. Much work remains to be done in order to reach a perfect understanding of these languages whose direct line of descent is unknown, and which also adopted the cuneiform syllabary, such as the Hurrian written in the north of Syria and Mesopotamia. In addition, much work remains to be done by future generations of Assyriologists so that they might succeed in deciphering the cuneiform tablets unearthed to date, without taking into account those which, alas, are illegally excavated on a daily basis, whose archaeological context is entirely unknown.