Cuneiform Scripts: How do they work?

13 April 2015

An exhibition held at the Learning Centre of the Lille 3 University Library on the cuneiform scripts of the ancient Near East reprises, albeit in a different form, the one organised in 2007 by a team from the CNRS (Nanterre) to mark the 150th anniversary of the decipherment of the Akkadian language in cuneiform script.

The latter exhibition gave rise to the publication of a dedicated booklet.

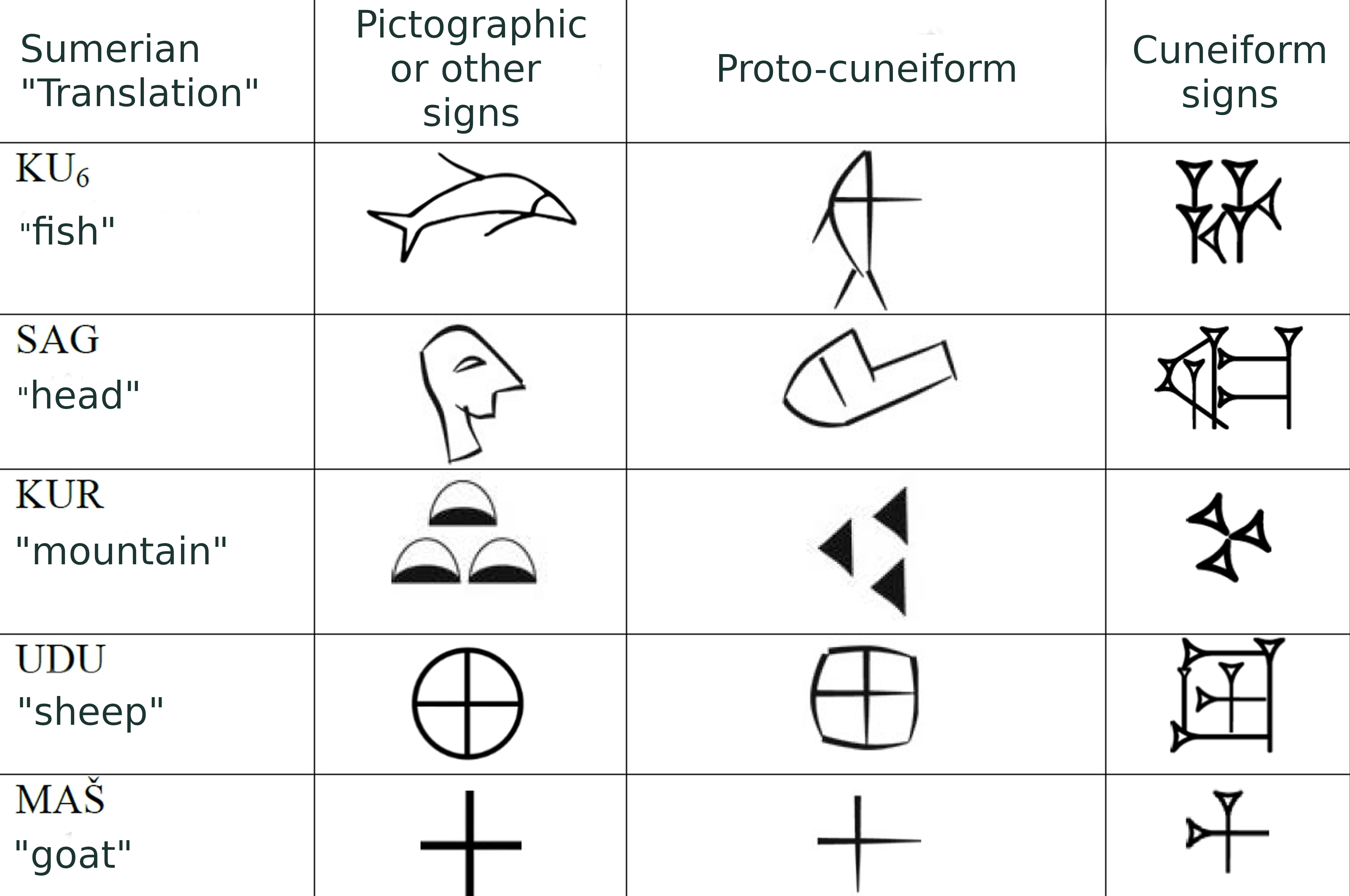

Used throughout the ancient Near East – from Anatolia to Iran, from Egypt to Mount Elbrus – cuneiform script served to set down in writing about a dozen different languages over the three and half millennia or so of their existence. Three writing systems were employed: logographic, where a sign is used to represent a word; syllabic, where a sign represents a syllable; and alphabetic. The Sumerians, who were in all probability the inventers of such notation in around 3400 BCE, called the writing ‘triangles’. The Western Europeans who rediscovered it in about 1700 CE named it cuneiform (i.e. ‘in the shape of a wedge’, from the Latin cuneus, meaning ‘wedge, or wedge-shaped’). In the beginning, though, the signs were not angular in form. Rather, they resembled small drawings, pictographic or otherwise, which is to say they sometimes depicted what they were intended to express: a fish, a head, or a mountain are rendered through figurative drawings. Then again, other signs did not bear a visual relationship to reality: for example, the sign for a sheep is a cross drawn within a circle. Some see a sheep within its enclosure, or a representation of a skein of wool, or even more simply a variant of the sign for a young goat (i.e. kid) rendered by means of a simple cross. Because it is difficult to inscribe curved lines in soft clay, the chief support for cuneiform script, curves were substituted with segments formed from straight lines imprinted into the clay using a cut reed of square or triangular section. At the same time, the signs undergo a quarter turn towards the left, and are read from left to right.

Logographic writing entails learning several hundred signs. Their number can be reduced by emphasising certain parts of the signs by means of hatching (the lower part of the head, for example), or by combining several signs. To write in Sumerian, one must know more than 800 cuneiform signs, which would suggest that the number of literate people was not great.

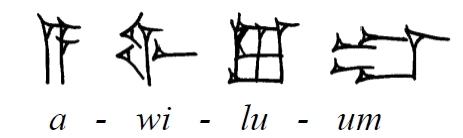

Just as in Chinese, Sumerian is composed in large part of monosyllabic words. When the Akkadians settled in Mesopotamia in the middle of the third millennium BCE, they adopted cuneiform script to write down their language, a language that belongs to the Semitic family of languages, like Arabic and Hebrew. They ignored the meaning of the signs, and instead used their sounds. They broke down their words into syllables: each syllable therefore corresponds to a sign. The word awīlum, which means man in Akkadian, is written thus:

This writing system, which requires about 120 signs, is a lot easier to learn. However, the Akkadians retained several dozen Sumerian logograms for commonly occurring words or as determinatives placed before or after words so as to place them in particular classes (e.g. names of gods, towns and countries). In the second and first millennia, Akkadian was divided into two principal dialects: Assyrian in the North and Babylonian in the South. Some other languages belonging to different linguistic families used this syllabic cuneiform writing system; among them were Elamite, Hurrian, Urartian and Hittite, an Indo-European language, like French.

In the fourteenth century BCE, at Ugarit, on the Levantine coast, a cuneiform alphabet was used to transcribe Ugaritic, a West-Semitic language. The 30 signs that compose the Ugaritic alphabet represent only consonants. This alphabet, which was used in parallel with Akkadian, was written in cuneiform syllables. It disappeared at the beginning of the twelfth century BCE with Ugarit’s downfall. Another alphabetic system that employed cuneiform was devised at the end of the sixth century BCE by the Achaemenid Empire in Iran to write down Old Persian. It consists of 40 signs, including the three vowels a, i and u, as well as 33 vocalised consonants. Like the Ugaritic alphabet, the Old Persian alphabet did not survive the eventual fall of the Achaemenid Empire in the fourth century BCE. The most recent tablets date to the first century BCE; these are astronomic texts written in Babylonian using the syllabic system.

Cuneiform script impressed in three dimensions into soft clay is very easy to write: indeed, it is an ingenious system! One only has to know how to inscribe the three basic wedge forms: the horizontal wedge (sometimes slanted); the vertical wedge; and the head of the wedge. Each individual sign is composed of a variable number of these three types of wedge form. The challenge lies in learning by heart hundreds of signs. However, depending on the historical period and milieu concerned, the number of signs can vary: Assyrian merchants of the nineteenth century BCE employed a syllabary that was limited to a hundred syllabic signs and about fifty logograms. The studies in progress on their archives and the identities of the scribes concerned have indicated that a significant proportion of the population, both men and women, was able to read and write.[1]

A short film titled ‘Cuneiform Script, Writing and Counting’ enables us to recreate the writing gestures used by ancient scribes. The film was shown at an exhibition held in Lille and can be viewed online, where it is accompanied by a teaching guide.

[1] Hilgert, Markus (2014), ‘Les pratiques variables de l’écriture: le cas des marchands assyriens’, Pour la Science 440, 53.